Recyclers Switch from Smelting to Solvents, Recovering Precious Metals from E-waste with Fewer Emissions

Who invented the light bulb?

Ernest Freeberg, University of Tennessee

Curious Kids is a series for children of all ages. If you have a question you’d like an expert to answer, send it to CuriousKidsUS@theconversation.com.

Who invented the light bulb? – Preben, age 5, New York City

When people name the most important inventions in history, light bulbs are usually on the list. They were much safer than earlier light sources, and they made more activities, for both work and play, possible after the Sun went down.

More than a century after its invention, illustrators still use a lit bulb to symbolize a great idea. Credit typically goes to inventor and entrepreneur Thomas Edison, who created the first commercial light and power system in the United States.

But as a historian and author of a book about how electric lighting changed the U.S., I know that the actual story is more complicated and interesting. It shows that complex inventions are not created by a single genius, no matter how talented he or she may be, but by many creative minds and hands working on the same problem.

Making light − and delivering it

In the 1870s, Edison raced against other inventors to find a way of producing light from electric current. Americans were keen to give up their gas and kerosene lamps for something that promised to be cleaner and safer. Candles offered little light and posed a fire hazard. Some customers in cities had brighter gas lamps, but they were expensive, hard to operate and polluted the air.

When Edison began working on the challenge, he learned from many other inventors’ ideas and failed experiments. They all were trying to figure out how to send a current through a thin carbon thread encased in glass, making it hot enough to glow without burning out.

In England, for example, chemist Joseph Swan patented an incandescent bulb and lit his own house in 1878. Then in 1881, at a great exhibition on electricity in Paris, Edison and several other inventors demonstrated their light bulbs.

Edison’s version proved to be the brightest and longest-lasting. In 1882 he connected it to a full working system that lit up dozens of homes and offices in downtown Manhattan.

But Edison’s bulb was just one piece of a much more complicated system that included an efficient dynamo – the powerful machine that generated electricity – plus a network of underground wires and new types of lamps. Edison also created the meter, a device that measured how much electricity each household used, so that he could tell how much to charge his customers.

Edison’s invention wasn’t just a science experiment – it was a commercial product that many people proved eager to buy.

Inventing an invention factory

As I show in my book, Edison did not solve these many technical challenges on his own.

At his farmhouse laboratory in Menlo Park, New Jersey, Edison hired a team of skilled technicians and trained scientists, and he filled his lab with every possible tool and material. He liked to boast that he had only a fourth grade education, but he knew enough to recruit men who had the skills he lacked. Edison also convinced banker J.P. Morgan and other investors to provide financial backing to pay for his experiments and bring them to market.

Historians often say that Edison’s greatest invention was this collaborative workshop, which he called an “invention factory.” It was capable of launching amazing new machines on a regular basis. Edison set the agenda for its work – a role that earned him the nickname “the wizard of Menlo Park.”

Here was the beginning of what we now call “research and development” – the network of universities and laboratories that produce technological breakthroughs today, ranging from lifesaving vaccines to the internet, as well as many improvements in the electric lights we use now.

Sparking an electric revolution

Many people found creative ways to use Edison’s light bulb. Factory owners and office managers installed electric light to extend the workday past sunset. Others used it for fun purposes, such as movie marquees, amusement parks, store windows, Christmas trees and evening baseball games.

Theater directors and photographers adapted the light to their arts. Doctors used small bulbs to peer inside the body during surgery. Architects and city planners, sign-makers and deep-sea explorers adapted the new light for all kinds of specialized uses. Through their actions, humanity’s relationship to day and night was reinvented – often in ways that Edison never could have anticipated.

Today people take for granted that they can have all the light they need at the flick of a switch. But that luxury requires a network of power stations, transmission lines and utility poles, managed by teams of trained engineers and electricians. To deliver it, electric power companies grew into an industry monitored by insurance companies and public utility regulators.

Edison’s first fragile light bulbs were just one early step in the electric revolution that has helped create today’s richly illuminated world.

Hello, curious kids! Do you have a question you’d like an expert to answer? Ask an adult to send your question to CuriousKidsUS@theconversation.com. Please tell us your name, age and the city where you live.

And since curiosity has no age limit – adults, let us know what you’re wondering, too. We won’t be able to answer every question, but we will do our best.![]()

Ernest Freeberg, Professor of History, University of Tennessee

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

What are climate tipping points? They sound scary, especially for ice sheets and oceans, but there’s still room for optimism

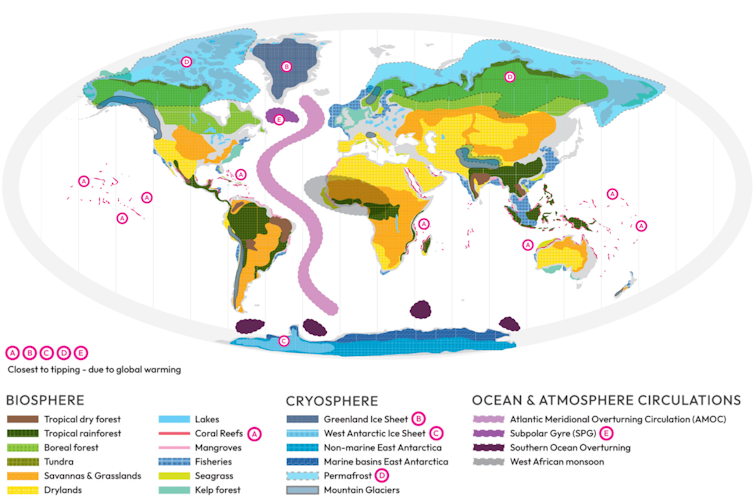

Pink circles show the systems closest to tipping points. Some would have regional effects, such as loss of coral reefs. Others are global, such as the beginning of the collapse of the Greenland ice sheet. Global Tipping Points Report, CC BY-ND

Pink circles show the systems closest to tipping points. Some would have regional effects, such as loss of coral reefs. Others are global, such as the beginning of the collapse of the Greenland ice sheet. Global Tipping Points Report, CC BY-NDScientists have long warned that if global temperatures warmed more than 1.5 degrees Celsius (2.7 Fahrenheit) compared with before the Industrial Revolution, and stayed high, they would increase the risk of passing multiple tipping points. For each of these elements, like the Amazon rain forest or the Greenland ice sheet, hotter temperatures lead to melting ice or drier forests that leave the system more vulnerable to further changes.

Worse, these systems can interact. Freshwater melting from the Greenland ice sheet can weaken ocean currents in the North Atlantic, disrupting air and ocean temperature patterns and marine food chains.

Pink circles show the systems closest to tipping points. Some would have regional effects, such as loss of coral reefs. Others are global, such as the beginning of the collapse of the Greenland ice sheet. Global Tipping Points Report, CC BY-ND

Pink circles show the systems closest to tipping points. Some would have regional effects, such as loss of coral reefs. Others are global, such as the beginning of the collapse of the Greenland ice sheet. Global Tipping Points Report, CC BY-NDWith these warnings in mind, 194 countries a decade ago set 1.5 C as a goal they would try not to cross. Yet in 2024, the planet temporarily breached that threshold.

The term “tipping point” is often used to illustrate these problems, but apocalyptic messages can leave people feeling helpless, wondering if it’s pointless to slam the brakes. As a geoscientist who has studied the ocean and climate for over a decade and recently spent a year on Capitol Hill working on bipartisan climate policy, I still see room for optimism.

It helps to understand what a tipping point is – and what’s known about when each might be reached.

Tipping points are not precise

A tipping point is a metaphor for runaway change. Small changes can push a system out of balance. Once past a threshold, the changes reinforce themselves, amplifying until the system transforms into something new.

Almost as soon as “tipping points” entered the climate science lexicon — following Malcolm Gladwell’s 2000 book, “The Tipping Point: How Little Things Can Make a Big Difference” — scientists warned the public not to confuse global warming policy benchmarks with precise thresholds.

The scientific reality of tipping points is more complicated than crossing a temperature line. Instead, different elements in the climate system have risks of tipping that increase with each fraction of a degree of warming.

For example, the beginning of a slow collapse of the Greenland ice sheet, which could raise global sea level by about 24 feet (7.4 meters), is one of the most likely tipping elements in a world more than 1.5 C warmer than preindustrial times. Some models place the critical threshold at 1.6 C (2.9 F). More recent simulations estimate runaway conditions at 2.7 C (4.9 F) of warming. Both simulations consider when summer melt will outpace winter snow, but predicting the future is not an exact science.

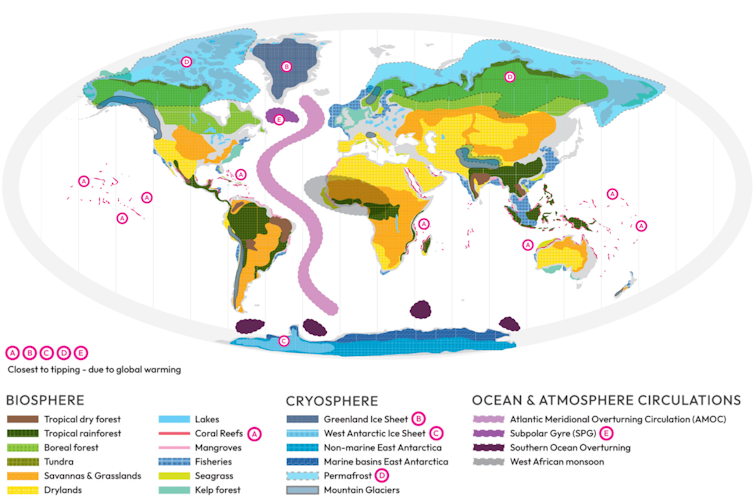

Gradients show science-based estimates from the Global Tipping Points Report of when some key global or regional climate tipping points are increasingly likely to be reached. Every fraction of a degree increases the likeliness, reflected in the warming color. Global Tipping Points Report 2025, CC BY-ND

Gradients show science-based estimates from the Global Tipping Points Report of when some key global or regional climate tipping points are increasingly likely to be reached. Every fraction of a degree increases the likeliness, reflected in the warming color. Global Tipping Points Report 2025, CC BY-NDForecasts like these are generated using powerful climate models that simulate how air, oceans, land and ice interact. These virtual laboratories allow scientists to run experiments, increasing the temperature bit by bit to see when each element might tip.

Climate scientist Timothy Lenton first identified climate tipping points in 2008. In 2022, he and his team revisited temperature collapse ranges, integrating over a decade of additional data and more sophisticated computer models.

Their nine core tipping elements include large-scale components of Earth’s climate, such as ice sheets, rain forests and ocean currents. They also simulated thresholds for smaller tipping elements that pack a large punch, including die-offs of coral reefs and widespread thawing of permafrost.

The world may have already passed one tipping point, according to the 2025 Global Tipping Points Report: Corals reefs are dying as marine temperatures rise. Healthy reefs are essential fish nurseries and habitat and also help protect coastlines from storm erosion. Once they die, their structures begin to disintegrate. Vardhan Patankar/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA

The world may have already passed one tipping point, according to the 2025 Global Tipping Points Report: Corals reefs are dying as marine temperatures rise. Healthy reefs are essential fish nurseries and habitat and also help protect coastlines from storm erosion. Once they die, their structures begin to disintegrate. Vardhan Patankar/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA

Some tipping elements, such as the East Antarctic ice sheet, aren’t in immediate danger. The ice sheet’s stability is due to its massive size – nearly six times that of the Greenland ice sheet – making it much harder to push out of equilibrium. Model results vary, but they generally place its tipping threshold between 5 C (9 F) and 10 C (18 F) of warming.

Other elements, however, are closer to the edge.

Alarm bells sounding in forests and oceans

In the Amazon, self-perpetuating feedback loops threaten the stability of the Earth’s largest rain forest, an ecosystem that influences global climate. As temperatures rise, drought and wildfire activity increase, killing trees and releasing more carbon into the atmosphere, which in turn makes the forest hotter and drier still.

By 2050, scientists warn, nearly half of the Amazon rain forest could face multiple stressors. That pressure may trigger a tipping point with mass tree die-offs. The once-damp rain forest canopy could shift to a dry savanna for at least several centuries.

Rising temperatures also threaten biodiversity underwater.

The second Global Tipping Points Report, released Oct. 12, 2025, by a team of 160 scientists including Lenton, suggests tropical reefs may have passed a tipping point that will wipe out all but isolated patches.

Corals rely on algae called zooxanthellae to thrive. Under heat stress, the algae leave their coral homes, draining reefs of nutrition and color. These mass bleaching events can kill corals, stripping the ecosystem of vital biodiversity that millions of people rely on for food and tourism.

Low-latitude reefs have the highest risk of tipping, with the upper threshold at just 1.5 C, the report found. Above this amount of warming, there is a 99% chance that these coral reefs tip past their breaking point.

Similar alarms are ringing for ocean currents, where freshwater ice melt is slowing down a major marine highway that circulates heat, known as the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation, or AMOC.

A weaker current could create a feedback loop, slowing the circulation further and leading to a shutdown within a century once it begins, according to one estimate. Like a domino, the climate changes that would accompany an AMOC collapse could worsen drought in the Amazon and accelerate ice loss in the Antarctic.

Questions about closeness of other tipping points

Not all scientists agree that an AMOC or rain forest collapse is close.

In the Amazon, researchers recognize the forest’s changes, but some have questioned whether some of the modeled vegetation data that underpins tipping point concerns is accurate. In the North Atlantic, there are similar concerns about data showing a long-term trend.

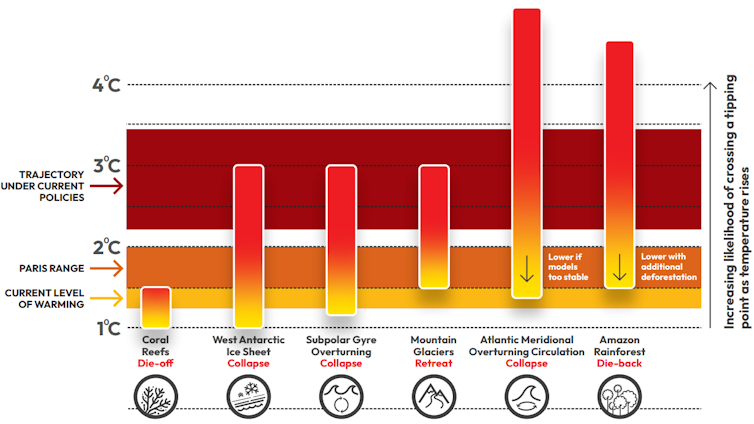

The Amazon forest has been losing tree cover to logging, farming, ranching, wildfires and a changing climate. Pink shows areas with greater than 75% tree canopy loss from 2001 to 2024. Blue is tree cover gain from 2000 to 2020. Global Forest Watch, CC BY

The Amazon forest has been losing tree cover to logging, farming, ranching, wildfires and a changing climate. Pink shows areas with greater than 75% tree canopy loss from 2001 to 2024. Blue is tree cover gain from 2000 to 2020. Global Forest Watch, CC BYOther changes driven by rising global temperatures, like melting permafrost, could be reversed. Permafrost, for example, could refreeze if temperatures drop again.

Risks are too high to ignore

Despite the uncertainty, tipping points are too risky to ignore. Rising temperatures put people and economies around the world at greater risk of dangerous conditions.

But there is still room for preventive actions – every fraction of a degree in warming that humans prevent reduces the risk of runaway climate conditions. Reducing greenhouse gas emissions slows warming and tipping point risks.

Tipping points highlight the stakes, but they also underscore the climate choices humanity can still make to stop the damage.

This article was updated to clarify permafrost discussion.![]()

Alexandra A Phillips, Assistant Teaching Professor in Environmental Communication, University of California, Santa Barbara

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Climate change is a crisis of intergenerational justice. It’s not too late to make it right

Philippa Collin, Western Sydney University; Judith Bessant, RMIT University, and Rob Watts, RMIT University

Climate change is the biggest issue of our time. 2024 marked both the hottest year on record and the highest levels of carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions in the past two million years.

Global warming increases the frequency and severity of extreme weather events, bushfires, floods and droughts. These are already affecting young people, who will experience the challenges for more of their lives than older people.

It will also adversely affect those not yet born, creating a crisis of intergenerational justice.

Caught in the changing climate

In 2025, children and young people comprise a third of Australia’s population.

Given their early stage of physiological and cognitive development, children are more vulnerable to climate disasters such as crop failures, river floods and drought.

They are also less able to protect themselves from the associated trauma than most older people.

Under current emissions trajectories, United Nations research warns every child in Australia could be subject to more than four heatwaves a year. It’s estimated more than two million Australian children could be living in areas where heatwaves will last longer than four days.

A recent report found more than one million children and young people in Australia experience a climate disaster or extreme weather event in an “average year”.

Those in remote areas, from lower socioeconomic backgrounds and Indigenous children are more likely to be negatively effected. That’s equivalent to one in six children, and numbers are rising.

Anxiety, frustration and fear

The impact of climate change on young people’s health and wellbeing is also significant. Globally, young people bear the greatest psychological burden associated with the impacts of climate change.

Feelings such as frustration, fear and anxiety related to climate change are compounded by the experience of extreme weather events and associated health impacts.

Intergenerational inequality is the term on the lips of policymakers in Canberra and beyond. In this four-part series, we’ve asked leading experts what’s making younger generations worse off and how policy could help fix it.

For young people who live through climate-related disasters, they may experience challenges with education, displacement, housing insecurity and financial difficulties.

All these come on top of other issues. These include increased socioeconomic inequality, rising child poverty, mounting education debt, precarious employment, and lack of access to affordable housing.

This means this generation of young people is likely to be worse off economically than their parents.

Not walking the walk

Some key policy figures understand how climate change is turbo-charging intergenerational unfairness.

Former treasury secretary Ken Henry described the situation as an “intergenerational tragedy”, referring to the ways Australian policymakers are failing to address the changing climate, among other crucial issues.

Even Treasurer Jim Chalmers acknowledged “intergenerational fairness is one of the defining principles of our country”.

Yet, the current responses to the Climate Risk Assessment Report suggest it’s not the highest priority.

Climate change was barely mentioned in the May 2025 federal election. The major parties largely avoided the subject.

It was also concerning that the first major decision of the newly reelected Albanese government was approving an extension to Woodside’s North West Shelf gas project off Western Australia until 2070.

This leaves a legacy to young people of an additional 87 million tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent every year for many years to come.

Raising young voices

Australia’s children and young people are not stupid. Many worked out early that they could not trust governments.

Since 2018, young people have mobilised hundreds of thousands of other children in protests calling for climate action.

Youth-led organisations in Australia, such as the Australian Youth Climate Coalition, have long led campaigns and strategies to address climate change. They are joined by an increasing range of older allies, from Parents for Climate to the Knitting Nannas to the Country Women’s Association.

Domestically, many young people have turned to strategic climate litigation and collaboration with members of parliament on legislative change. They argue governments have a legal duty of care to prevent the harms of climate change.

Thwarted attempts

Beyond accelerating implementation of the National Adaptation Plan, other legislative innovations will help.

In 2023, young people worked with independent Senator David Pocock to draft legislation addressing these concerns.

This bill required governments to consider the health and wellbeing of children and future generations when deciding on projects that could exacerbate climate change.

It was sent to the Senate Environment and Communications Legislation Committee. While all but one of 403 public submissions to the committee supported the bill, in June 2024 the Labor and Coalition members agreed to reject it. They argued it was difficult to quantify notions such as “wellbeing” or “material risk”.

Adding insult to injury, both major parties claimed Australia already had more than adequate environmental laws in place to protect children.

Turning around the Titanic

The Australian parliament may have another opportunity to embed a legislative duty to protect children and secure intergenerational justice. Independent MP Sophie Scamps introduced the Wellbeing of Future Generations Bill in February 2025. As legislation brought before the parliament lapses once an election is called, Scamps is planning to reintroduce the bill in this sitting term.

The bill would introduce a legislative framework to embed the wellbeing of future generations into decision making processes. It would also establish a positive duty and create an independent commissioner for future generations to advocate for Australia’s long-term interests and sustainable practice.

While this bill does not include penalties for breaches of the duty, if passed, it would force the government of the day to consider the rights and interests of current and future generations.

It’s based on similar legislation in Wales, which has worked successfully for a decade.

If nothing else, the Welsh experiment suggests we can take entirely practical steps to promote intergenerational justice, reduce the negative impacts of climate change on young people right now and avert a climate catastrophe threatening our children who are yet to be born.

It may feel like turning around the Titanic, but it must be done.![]()

Philippa Collin, Professor of Political Sociology, Institute for Culture and Society, Western Sydney University; Judith Bessant, Distinguished Professor in School of Global, Urban and Social Studies, RMIT University, and Rob Watts, Professor of Social Policy, RMIT University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Six Baby Cheetahs Born in the Richmond Zoo's Prolific Breeding Program – 167 Cats Since 2013 (WATCH)

Researchers Test Use of Nuclear Technology to Curb Rhino Poaching in South Africa

Scientists Find Answer to Sea Star Population Devastated by Pathogen Along the California Coast

A sunflower sea star – credit, Ed Bierman CC 2.0.

A sunflower sea star – credit, Ed Bierman CC 2.0.With the cause identified, a large collaboration involving Prentice’s Hakai Institute, as well as the universities of British Columbia and Washington, the Nature Conservancy, Tula Foundation, US Geological Survey, and the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife, are beginning to plan strategies for the sea stars’ recovery.

The science behind a freediver’s 29-minute breath hold world record

Most of us can hold our breath for between 30 and 90 seconds.

A few minutes without oxygen can be fatal, so we have an involuntary reflex to breathe.

But freediver Vitomir Maričić recently held his breath for a new world record of 29 minutes and three seconds, lying on the bottom of a 3-metre-deep pool in Croatia.

This is about five minutes longer than the previous world record set in 2021 by another Croatian freediver, Budimir Šobat.

Interestingly, all world records for breath holds are by freedivers, who are essentially professional breath-holders.

They do extensive physical and mental training to hold their breath under water for long periods of time.

So how do freedivers delay a basic human survival response and how was Maričić able to hold his breath about 60 times longer than most people?

Increased lung volumes and oxygen storage

Freedivers do cardiovascular training – physical activity that increases your heart rate, breathing and overall blood flow for a sustained period – and breathwork to increase how much air (and therefore oxygen) they can store in their lungs.

This includes exercise such as swimming, jogging or cycling, and training their diaphragm, the main muscle of breathing.

Diaphragmatic breathing and cardiovascular exercise train the lungs to expand to a larger volume and hold more air.

This means the lungs can store more oxygen and sustain a longer breath hold.

Freedivers can also control their diaphragm and throat muscles to move the stored oxygen from their lungs to their airways. This maximises oxygen uptake into the blood to travel to other parts of the body.

To increase the oxygen in his lungs even more before his world record breath-hold, Maričić inhaled pure (100%) oxygen for ten minutes.

This gave Maričić a larger store of oxygen than if he breathed normal air, which is only about 21% oxygen.

This is classified as an oxygen-assisted breath-hold in the Guiness Book of World Records.

Even without extra pure oxygen, Maričić can hold his breath for 10 minutes and 8 seconds.

Resisting the reflex to take another breath

Oxygen is essential for all our cells to function and survive. But it is high carbon dioxide, not low oxygen that causes the involuntary reflex to breathe.

When cells use oxygen, they produce carbon dioxide, a damaging waste product.

Carbon dioxide can only be removed from our body by breathing it out.

When we hold our breath, the brain senses the build-up in carbon dioxide and triggers us to breathe again.

Freedivers practice holding their breath to desensitise their brains to high carbon dioxide and eventually low oxygen. This delays the involuntary reflex to breathe again.

When someone holds their breath beyond this, they reach a “physiological break-point”. This is when their diaphragm involuntarily contracts to force a breath.

This is physically challenging and only elite freedivers who have learnt to control their diaphragm can continue to hold their breath past this point.

Indeed, Maričić said that holding his breath longer:

got worse and worse physically, especially for my diaphragm, because of the contractions. But mentally I knew I wasn’t going to give up.

Mental focus and control is essential

Those who freedive believe it is not only physical but also a mental discipline.

Freedivers train to manage fear and anxiety and maintain a calm mental state. They practice relaxation techniques such as meditation, breath awareness and mindfulness.

Interestingly, Maričić said:

after the 20-minute mark, everything became easier, at least mentally.

Reduced mental and physical activity, reflected in a very low heart rate, reduces how much oxygen is needed. This makes the stored oxygen last longer.

That is why Maričić achieved this record lying still on the bottom of a pool.

Don’t try this at home

Beyond competitive breath-hold sports, many other people train to hold their breath for recreational hunting and gathering.

For example, ama divers who collect pearls in Japan, and Haenyeo divers from South Korea who harvest seafood.

But there are risks of breath holding.

Maričić described his world record as:

a very advanced stunt done after years of professional training and should not be attempted without proper guidance and safety.

Indeed, both high carbon dioxide and a lack of oxygen can quickly lead to loss of consciousness.

Breathing in pure oxygen can cause acute oxygen toxicity due to free radicals, which are highly reactive chemicals that can damage cells.

Unless you’re trained in breath holding, it’s best to leave this to the professionals.![]()

Theresa Larkin, Associate Professor of Medical Sciences, University of Wollongong and Gregory Peoples, Senior Lecturer - Physiology, University of Wollongong

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

UK’s Rarest Breeding Birds Raise Chicks for First Time in Six Years

A male Montagu’s harrier in a wheat field – credit, Sumeetmoghe CC 4.0. BY-SA

A male Montagu’s harrier in a wheat field – credit, Sumeetmoghe CC 4.0. BY-SAResearchers Test Use of Nuclear Technology to Curb Rhino Poaching in South Africa

Curious Kids: Why do dolphins jump out of the water?

Have you ever seen images of dolphins jumping out of the waves and performing impressive acrobatics in the air? Or maybe you’ve seen it in real life?

When a dolphin jumps, it can launch its whole body out of the water. While it looks like fun, it must also be hard work!

So, why do dolphins jump out of the water? There are several possible reasons. Let’s jump in and explore them.

To stay in touch

Dolphins are social animals and live in groups. But it’s hard to see long distances underwater. So, they use the power of sound to stay in contact with each other.

Sound travels much farther underwater than through the air. When dolphins jump, the slap of the landing makes a loud noise, and would be heard some distance away.

Some species, such as spinner dolphins, use jumping to communicate their location to other group members, especially at night. This helps them keep track of each other.

As an aside, spinner dolphins are very skilled jumpers. As the name suggests, they spin up to seven times in the air before landing back in the water!

The need for speed

Have you ever tried to walk underwater? You will have felt how hard it is. That’s because water is more dense than air, which creates a “drag”, or resistance.

Dolphins have streamlined bodies to reduce drag, but they still feel it. So, if they want to travel quickly – for example, if they are trying to escape a predator or hunt fish – they sometimes jump.

While in the air, they travel faster than they would through water, and also save energy.

To gather food

Some dolphins weigh less than 50 kilograms, such as the Hector’s dolphin. Others weigh several tonnes, such as an orca.

Either way, when a dolphin crashes back into the water, you can be sure it makes quite a noisy splash.

Some dolphin species, such as dusky dolphins, use this noise to herd fish at the surface to make them easier to capture.

Shaking off hitchhikers

Fish called remoras can attach themselves to dolphins using a sucker on their head. This is good for the fish, because it can keep them safe and they have plenty to eat, such as small parasites and old bits of dolphin skin.

While the remoras don’t hurt the dolphin, they probably slow it down. So dolphins may try to get rid of the little hitchhikers by jumping to dislodge them.

Fighting and frolicking

Dolphins are highly intelligent animals. They have big brains and can learn tricks and solve puzzles. With intelligence also come other traits: playfulness and social behaviour.

Sometimes, that social behaviour can end in a “fight”. Dolphin experts say two dolphins jumping around together might be actually trying to hit each other!

Dolphins also love to frolic – not just with each other but with other marine mammals such as whales and sea lions, with turtles – or even just a piece of seaweed! So they might jump as some sort of “game”.

As you can see, dolphins may jump for a range of reasons – sometimes just because it’s really fun!![]()

Katharina J. Peters, Lecturer in Biological Sciences, University of Wollongong

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

How math and impatient driving inspired student's award-winning startup

Scientists in Japan Develop Non-Toxic Plastic That Dissolves in Seawater Within Hours

World's First Diamond Battery Could Power Spacecraft and Pacemakers for Thousands of Years

GNN-created image

GNN-created imagePhiladelphia Zoo’s 100-Year-old Galapagos Tortoises Hatch 4 Babies–to Help Ensure the Species’ Survival

Hatchlings of Western Santa Cruz Galapagos tortoise Credit: Philadelphia Zoo

Hatchlings of Western Santa Cruz Galapagos tortoise Credit: Philadelphia Zoo Galapagos tortoise egg hatched – Credit: Philadelphia Zoo

Galapagos tortoise egg hatched – Credit: Philadelphia Zoo