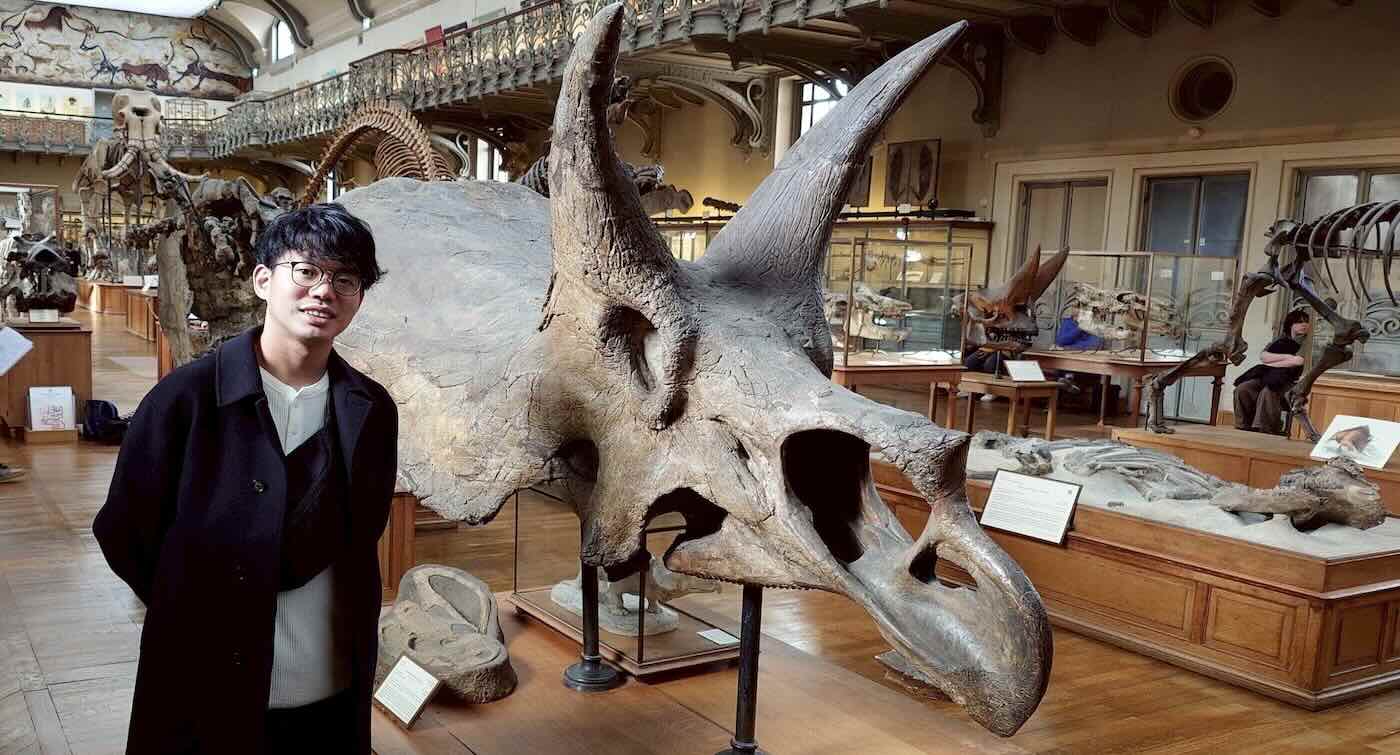

Seishiro Tada with fossilized Triceratops – SWNS

Seishiro Tada with fossilized Triceratops – SWNSScientists wanted to know why the iconic triceratops had such an unusually large nose compared to most species—both past and present.

Their new study shows the triple-horned dinosaur had a huge nose to help control its body temperature.

The team used CT scans of fossilized Triceratops skulls and compared their structures with modern animals including birds and crocodiles.

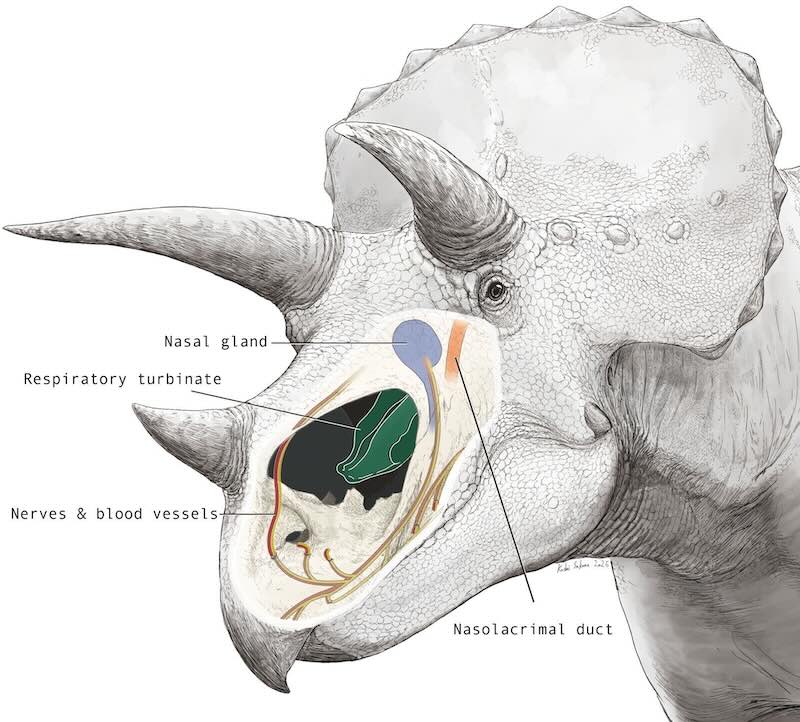

Through direct observation and inference, the research team reconstructed how nerves, blood vessels and structures for airflow fit together in the skulls.

They concluded that horned dinosaurs probably used their noses not just for smelling but also to help control temperature and moisture. Project Research Associate Dr. Seishiro Tada, from the University of Tokyo Museum in Japan, wondered about moisture control while studying a fossilized triceratops.

“I have been working on the evolution of reptilian heads and noses since my master’s degree,” said Dr. Tada.

“Triceratops in particular had a very large and unusual nose, and I couldn’t figure out how the organs fit within it even though I remember the basic patterns of reptiles.

“That made me interested in their nasal anatomy and its function and evolution.”

Horned dinosaurs (or Ceratopsia) had some of the most elaborate skull types—and Triceratops was the most iconic and instantly recognizable.

But due to its relative uniqueness, the internal anatomy of Triceratops skulls has been poorly understood, until Dr. Tada explored the internal soft tissues using modern tools at their disposal.

SWNS

SWNS“Employing X-ray-based CT-scan data of a Triceratops, as well as knowledge on contemporary reptilian snout morphology, we found some unique characteristics in the nose and provide the first comprehensive hypothesis on the soft-tissue anatomy in horned dinosaurs.

“Triceratops had unusual ‘wiring’ in their noses.

“In most reptiles, nerves and blood vessels reach the nostrils from the jaw and the nose. But in Triceratops, the skull shape blocks the jaw route, so nerves and vessels take the nasal branch.

“Essentially, Triceratops tissues evolved this way to support its big nose.

“I came to realize this while piecing together some 3D-printed Triceratops skull pieces like a puzzle.”

The findings, published in the journal The Anatomical Record, also revealed a special structure in Triceratops’ nose called a respiratory turbinate, which almost no other dinosaurs are known to possess. Yet modern birds have them, as do modern mammals.

The structures are thin, curled surfaces within the nose that increase the surface area for blood and air to exchange heat.

Dr Tada says Triceratops probably wasn’t fully warm-blooded, but the researchers believe the structures helped keep temperature and moisture levels under control as its large skull would be difficult to cool down otherwise.“Although we’re not 100% sure Triceratops had a respiratory turbinate, as most other dinosaurs don’t, some birds have an attachment base (ridge) for the turbinate. Horned dinosaurs have a similar ridge at the similar location in their nose as well. Triceratops Had Huge Nose to Control its Body Temperature, Suggests Curious Scientis