URI scientists believe birds can teach us about healthy eating

Red flowers have a ‘magic trait’ to attract birds and keep bees away

Joshua J. Cotten

Adrian Dyer, Monash University and Klaus Lunau, Heinrich Heine Universität Düsseldorf

Joshua J. Cotten

Adrian Dyer, Monash University and Klaus Lunau, Heinrich Heine Universität DüsseldorfFor flowering plants, reproduction is a question of the birds and the bees. Attracting the right pollinator can be a matter of survival – and new research shows how flowers do it is more intriguing than anyone realised, and might even involve a little bit of magic.

In our new paper, published in Current Biology, we discuss how a single “magic” trait of some flowering plants simultaneously camouflages them from bees and makes them stand out brightly to birds.

How animals see

We humans typically have three types of light receptors in our eyes, which enable our rich sense of colours.

These are cells sensitive to blue, green or red light. From the input from these cells, the brain generates many colours including yellow via what is called colour opponent processing.

The way colour opponent processing works is that different sensed colours are processed by the brain in opposition. For example, we see some signals as red and some as green – but never a colour in between.

Many other animals also see colour and show evidence of also using opponent processing.

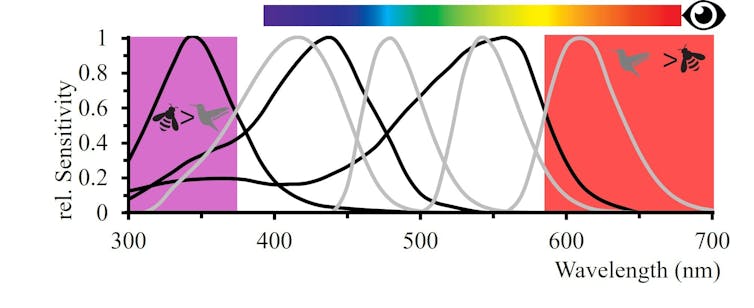

Bees see their world using cells that sense ultraviolet, blue and green light, while birds have a fourth type sensitive to red light as well.

Our colour perception illustrated with the spectral bar is different to bees that are sensitive to UV, blue and green, or birds with four colour photoreceptors including red sensitivity. Adrian Dyer & Klaus Lunau, CC BY

Our colour perception illustrated with the spectral bar is different to bees that are sensitive to UV, blue and green, or birds with four colour photoreceptors including red sensitivity. Adrian Dyer & Klaus Lunau, CC BYThe problem flowering plants face

So what do these differences in colour vision have to do with plants, genetics and magic?

Flowers need to attract pollinators of the right size, so their pollen ends up on the correct part of an animal’s body so it’s efficiently flown to another flower to enable pollination.

Accordingly, birds tend to visit larger flowers. These flowers in turn need to provide large volumes of nectar for the hungry foragers.

But when large amounts of sweet-tasting nectar are on offer, there’s a risk bees will come along to feast on it – and in the process, collect valuable pollen. And this is a problem because bees are not the right size to efficiently transfer pollen between larger flowers.

Flowers “signal” to pollinators with bright colours and patterns – but these plants need a signal that will attract birds without drawing the attention of bees.

We know bee pollination and flower signalling evolved before bird pollination. So how could plants efficiently make the change to being pollinated by birds, which enables the transfer of pollen over long distances?

Avoiding bees or attracting birds?

A walk through nature lets us see with our own eyes that most red flowers are visited by birds, rather than bees. So bird-pollinated flowers have successfully made the transition. Two different theories have been developed that may explain what we observe.

One theory is the bee avoidance hypotheses where bird pollinated flowers just use a colour that is hard for bees to see.

A second theory is that birds might prefer red.

But neither of these theories seemed complete, as inexperienced birds don’t demonstrate a preference for a stronger red hue. However, bird-pollinated flowers do have a very distinct red hue, which suggests avoiding bees can’t solely explain why consistently salient red flower colours evolved.

A magical solution

In evolutionary science, the term magic trait refers to an evolved solution where one genetic modification may yield fitness benefits in multiple ways.

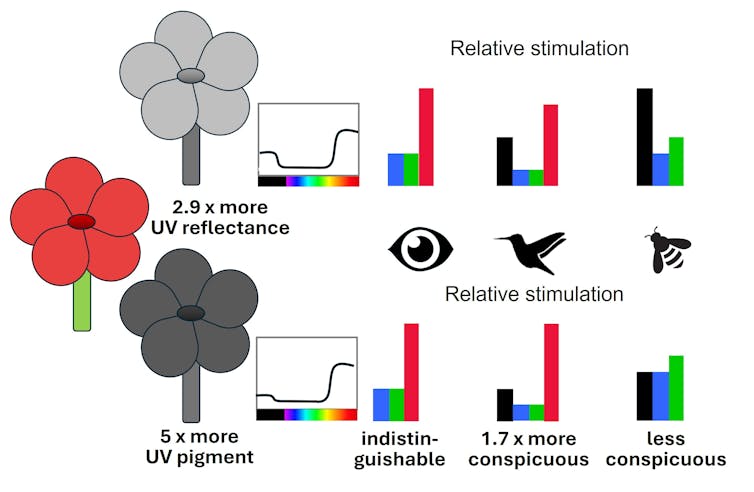

Earlier this month, a team working on how this might apply to flowering plants showed that a gene that modulates UV-absorbing pigments in flower petals can indeed have multiple benefits. This is because of how bees and birds view colour signals differently.

Bee-pollinated flowers come in a diverse range of colours. Bees even pollinate some plants with red flowers. But these flowers tend to also reflect a lot of UV, which helps bees find them.

The magic gene has the effect of reducing the amount of UV light reflected from the petal, making flowers harder for bees to see. But (and this is where the magic comes in) reducing UV reflection from a petal of a red flower simultaneously makes it look redder for animals – such as birds – which are believed to have a colour opponent system.

Red flowers look similar for humans, but as flowers evolved for bird vision a genetic change down-regulates UV reflection, making flowers more colourful for birds and less visible to bees. Adrian Dyer & Klaus Lunau, CC BY

Red flowers look similar for humans, but as flowers evolved for bird vision a genetic change down-regulates UV reflection, making flowers more colourful for birds and less visible to bees. Adrian Dyer & Klaus Lunau, CC BYBirds that visit these bright red flowers gain rewards – and with experience, they learn to go repeatedly to the red flowers.

One small gene change for colour signalling in the UV yields multiple beneficial outcomes by avoiding bees and displaying enhanced colours to entice multiple visits from birds.

We lucky humans are fortunate that our red perception can also see the result of this clever little trick of nature to produce beautiful red flower colours. So on your next walk on a nice day, take a minute to view one of nature’s great experiments on finding a clever solution to a complex problem.![]()

Adrian Dyer, Associate Professor, Department of Physiology, Monash University and Klaus Lunau, Professor, Institute of Sensory Ecology, Heinrich Heine Universität Düsseldorf

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Most red flowers are visited by birds, rather than bees.

Most red flowers are visited by birds, rather than bees.