The International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics (ICRISAT) on Thursday announced that its researchers are leading a transformation in crop testing, combining AI-driven models and pocket-size near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) devices.

These portable sensors allow for quick evaluation of nutrition levels in indigenous food grains right at the farmer's gate or in research fields.

ICRISAT Director General, Dr Jacqueline d'Arros Hughes, championed the integration of this disruptive technology into breeding pipelines and key points of relevant value chains.

Aligned with the UN Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) strategy, she foresees the tool as a catalyst for the production of nutrient-dense crops, both in breeding programmes and in farmers' fields, a crucial element in the global fight against malnutrition.

"This technology is poised to expedite the breeding of nutrient-dense crops while facilitating their integration into the value chain. Our goal with this intervention is to provide quality assurance for the distribution of nutritionally fortified crops, so that they reach those who need them most," she added.

Traditionally, assessing the nutritional quality of grains and feedstock could take a number of weeks, involving manual or partially automated processes and laboratory instruments.

In contrast, mobile NIRS devices are more cost-effective and can assess over 150 samples per day per person, ICRISAT said.

These non-destructive and robust grain quality measuring devices provide timely information on grain composition and can be used to promote quality-based payments in the market—benefiting food producers, grain processing industries, and farmers alike.

"We see the adoption of portable technology for assessing grain quality as an important step in decentralising and democratising market systems, essential to promote the consumption of nutri-cereals. This transition can facilitate quality-driven payments for farmers, while providing quality assurance to health-conscious households moving forward," noted Dr Sean Mayes, Global Research Director of the Accelerated Crop Improvement Program at ICRISAT.

In Anantapur in Andhra Pradesh, ICRISAT recommends its Girnar 4 groundnut variety to ensure premium prices for farmers and to differentiate the crop from lower-value varieties. ICRISAT's Girnar 4 and Girnar 5 groundnut varieties boast oleic acid levels of 75-80 per cent, far surpassing that of the standard variety at 40-50 per cent.

Oleic acid is a heart-healthy monounsaturated fatty acid, which holds considerable importance for the groundnut market, as it provides new end-uses for the crop. Growing consumer awareness of its advantages spurred market demand for high oleic acid content in oils and related products.

This pioneering approach, initially applied in peanut breeding, could be replicated across other crops, offering efficient and cost-effective solutions to address poor nutrition.

ICRISAT's Facility for Exploratory Research on Nutrition (FERN laboratory) is expanding its prediction models to encompass various traits and crops beyond groundnuts."We are currently focusing on developing methods to assess oil, oleic acid, linoleic acid, carotenoids, starch, moisture, and phosphorus in various cereals and legumes, such as finger millet, foxtail millet, pearl millet, sorghum, maize, wheat, chickpea, mungbean, common bean, pigeon pea, cowpea, soybean, groundnut, and mustard," said Dr Jana Kholova, Cluster Leader. Crop Physiology and Modelling, ICRISAT. ICRISAT develops portable technology for testing crops' nutrition level | MorungExpress | morungexpress.com

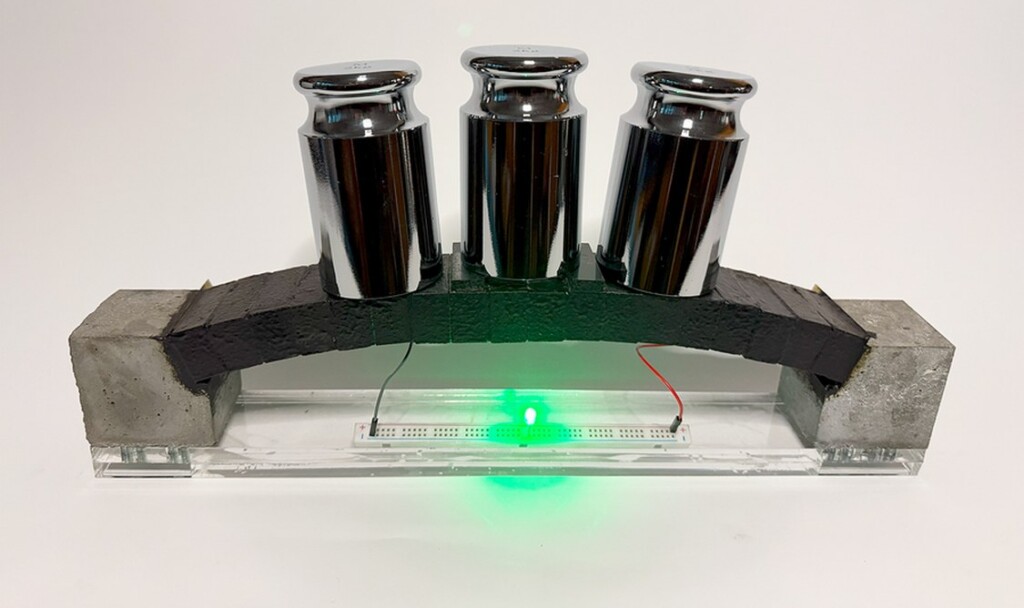

credit – MIT Sustainable Concrete Lab

credit – MIT Sustainable Concrete Lab