Australia’s sea surface temperatures were the warmest on record last year, according to a snapshot of the nation’s climate which underscores the perilous state of the world’s oceans.

The Bureau of Meteorology on Thursday released its annual climate statement for 2024 – the official record of temperature, rainfall, water resources, oceans, atmosphere and notable weather.

Among its many alarming findings were that sea surface temperatures were hotter than ever around the continent last year: a whopping 0.89°C above average.

Oceans cover more than 70% of Earth’s surface, and their warming is gravely concerning. It causes sea levels to rise, coral to bleach and Earth’s ice sheets to melt faster. Hotter oceans also makes weather on land more extreme and damages the marine life which underpins vital ocean ecosystems.

What the snapshot showed

Australia’s climate varies from year to year. That’s due to natural phenomena such as the El Niño and La Niña climate drivers, as well as human-induced climate change.

The bureau confirmed 2024 was Australia’s second-warmest year since national records began in 1910. The national annual average temperature was 1.46°C warmer than the long-term average (1961–90). Heatwaves struck large parts of Australia early in the year, and from September to December.

Average rainfall in Australia was 596 millimetres, 28% above the 30-year average, making last year the eighth-wettest since records began.

And annual sea surface temperatures for the Australian region were the warmest on record. Global sea surface temperatures in 2024 were also the warmest on record.

According to the bureau, Antarctic sea-ice extent was far below average, or close to record-lows, for much of the year but returned to average in December.

What caused the hot oceans?

It’s too early to officially attribute the ocean warming to climate change. But we do know greenhouse gas emissions are heating the Earth’s atmosphere, and oceans absorb 90% of this heat.

So we can expect human-induced climate change played a big role in warming the oceans last year. But shorter-term forces are at play, too.

The rare triple-dip La Niña Australia experienced from 2020 to 2023 brought cooler water from deep in the ocean up to the surface. It was like turning on the ocean’s air-conditioner.

But that pattern ended and Australia entered an El Niño in September 2023. It lasted about seven months, when the oscillation between El Niño and La Niña entered a neutral phase.

The absence of a La Niña meant cool water was no longer being churned up from the deep. Once that masking effect disappeared, the long-term warming trend of the oceans became apparent once more.

Water can store a lot more heat than air. In fact, just the top few metres of the ocean store as much heat as Earth’s entire atmosphere. Oceans take a long time to heat up and a long time to cool.

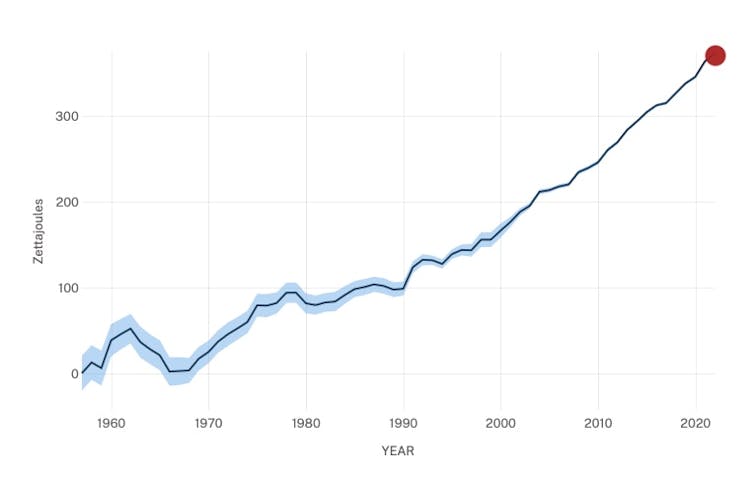

Heat at the ocean’s surface eventually gets pushed deeper into the water column and spreads across Earth’s surface in currents. The below chart shows how the world’s oceans have heated over the past 70 years. Changes in the world’s ocean heat content since 1955. NOAA/NCEI World Ocean Database

Changes in the world’s ocean heat content since 1955. NOAA/NCEI World Ocean Database

Why should we care about ocean warming?

Rapid warming of Earth’s oceans is setting off a raft of worrying changes.

It can lead to less nutrients in surface waters, which in turn leads to fewer fish. Warmer water can also cause species to move elsewhere. This threatens the food security and livelihoods of millions of people around the world.

Just last week, it was reported that tens of thousands of fish died off northwestern Australia due to a large and prolonged marine heatwave.

Warm water causes coral bleaching, as experienced on the Great Barrier Reef in recent decades. It also makes oceans more acidic, reducing the amount of calcium carbonate available for organisms to build shells and skeletons.

Warming oceans trigger sea level rise – both due to melt water from glaciers and ice sheets, and the fact seawater expands as it warms.

Hotter oceans are also linked to weather extremes, such as more intense cyclones and heavier rainfall. It’s likely the high annual rainfall Australia experienced in 2024 was in part due to warmer ocean temperatures.

What now?

As long as humans keep burning fossil fuels and pumping greenhouse gases into the atmosphere, the oceans will keep warming.

Unfortunately, the world is not doing a good job of shifting its emissions trajectory. As the bureau pointed out in its statement, concentrations of all major long-lived greenhouse gases in the atmosphere increased last year, including carbon dioxide and methane.

Prolonged ocean warming is driving changes in weather patterns and more frequent and intense marine heatwaves. This threatens ecosystems and human livelihoods. To protect our oceans and our way of life, we must transition to clean energy sources and cut carbon emissions.

At the same time, we must urgently expand ocean observing below the ocean’s surface, especially in under-studied regions, to establish crucial baseline data for measuring climate change impacts.

The time to act is now: to reduce emissions, support ocean research and help safeguard the future of our blue planet.![]()

Moninya Roughan, Professor in Oceanography, UNSW Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.