Most of us can hold our breath for between 30 and 90 seconds.

A few minutes without oxygen can be fatal, so we have an involuntary reflex to breathe.

But freediver Vitomir Maričić recently held his breath for a new world record of 29 minutes and three seconds, lying on the bottom of a 3-metre-deep pool in Croatia.

This is about five minutes longer than the previous world record set in 2021 by another Croatian freediver, Budimir Šobat.

Interestingly, all world records for breath holds are by freedivers, who are essentially professional breath-holders.

They do extensive physical and mental training to hold their breath under water for long periods of time.

So how do freedivers delay a basic human survival response and how was Maričić able to hold his breath about 60 times longer than most people?

Increased lung volumes and oxygen storage

Freedivers do cardiovascular training – physical activity that increases your heart rate, breathing and overall blood flow for a sustained period – and breathwork to increase how much air (and therefore oxygen) they can store in their lungs.

This includes exercise such as swimming, jogging or cycling, and training their diaphragm, the main muscle of breathing.

Diaphragmatic breathing and cardiovascular exercise train the lungs to expand to a larger volume and hold more air.

This means the lungs can store more oxygen and sustain a longer breath hold.

Freedivers can also control their diaphragm and throat muscles to move the stored oxygen from their lungs to their airways. This maximises oxygen uptake into the blood to travel to other parts of the body.

To increase the oxygen in his lungs even more before his world record breath-hold, Maričić inhaled pure (100%) oxygen for ten minutes.

This gave Maričić a larger store of oxygen than if he breathed normal air, which is only about 21% oxygen.

This is classified as an oxygen-assisted breath-hold in the Guiness Book of World Records.

Even without extra pure oxygen, Maričić can hold his breath for 10 minutes and 8 seconds.

Resisting the reflex to take another breath

Oxygen is essential for all our cells to function and survive. But it is high carbon dioxide, not low oxygen that causes the involuntary reflex to breathe.

When cells use oxygen, they produce carbon dioxide, a damaging waste product.

Carbon dioxide can only be removed from our body by breathing it out.

When we hold our breath, the brain senses the build-up in carbon dioxide and triggers us to breathe again.

Freedivers practice holding their breath to desensitise their brains to high carbon dioxide and eventually low oxygen. This delays the involuntary reflex to breathe again.

When someone holds their breath beyond this, they reach a “physiological break-point”. This is when their diaphragm involuntarily contracts to force a breath.

This is physically challenging and only elite freedivers who have learnt to control their diaphragm can continue to hold their breath past this point.

Indeed, Maričić said that holding his breath longer:

got worse and worse physically, especially for my diaphragm, because of the contractions. But mentally I knew I wasn’t going to give up.

Mental focus and control is essential

Those who freedive believe it is not only physical but also a mental discipline.

Freedivers train to manage fear and anxiety and maintain a calm mental state. They practice relaxation techniques such as meditation, breath awareness and mindfulness.

Interestingly, Maričić said:

after the 20-minute mark, everything became easier, at least mentally.

Reduced mental and physical activity, reflected in a very low heart rate, reduces how much oxygen is needed. This makes the stored oxygen last longer.

That is why Maričić achieved this record lying still on the bottom of a pool.

Don’t try this at home

Beyond competitive breath-hold sports, many other people train to hold their breath for recreational hunting and gathering.

For example, ama divers who collect pearls in Japan, and Haenyeo divers from South Korea who harvest seafood.

But there are risks of breath holding.

Maričić described his world record as:

a very advanced stunt done after years of professional training and should not be attempted without proper guidance and safety.

Indeed, both high carbon dioxide and a lack of oxygen can quickly lead to loss of consciousness.

Breathing in pure oxygen can cause acute oxygen toxicity due to free radicals, which are highly reactive chemicals that can damage cells.

Unless you’re trained in breath holding, it’s best to leave this to the professionals.![]()

Theresa Larkin, Associate Professor of Medical Sciences, University of Wollongong and Gregory Peoples, Senior Lecturer - Physiology, University of Wollongong

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

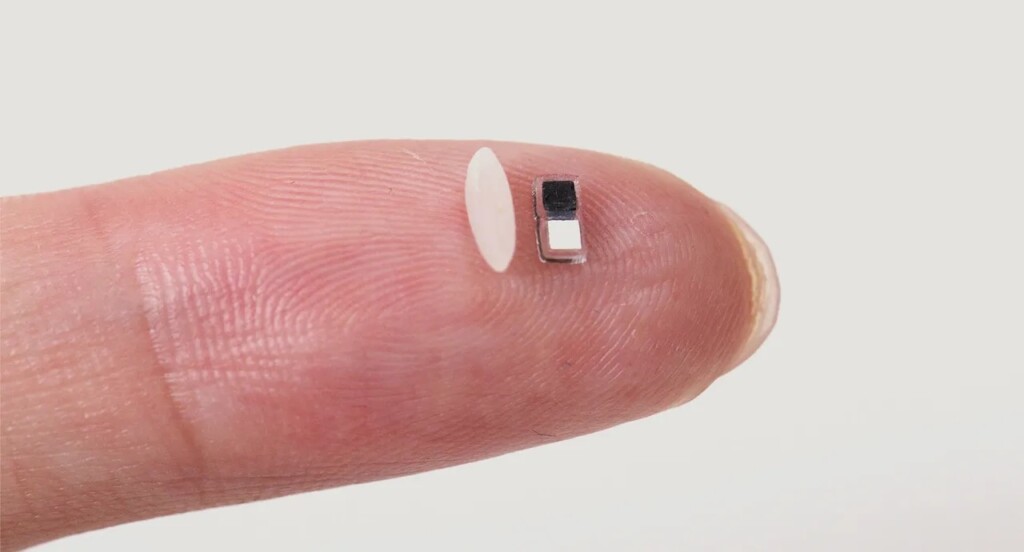

World’s smallest pacemaker next to a grain of rice – Credit: John Rogers / Northwestern University press release

World’s smallest pacemaker next to a grain of rice – Credit: John Rogers / Northwestern University press release