BirdCast

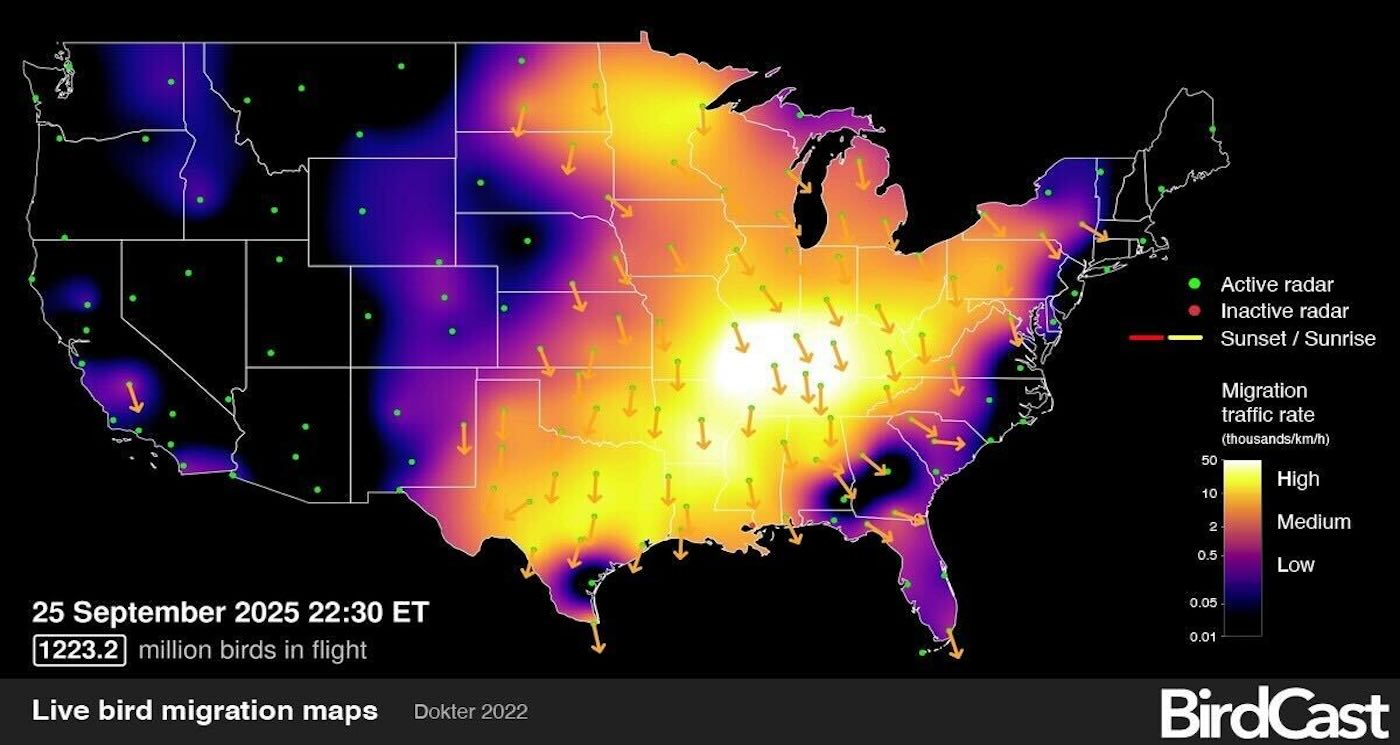

BirdCastMore than 1.2 billion birds streamed south in one night during their Fall migration in late September—the largest single-night total ever recorded by the American live radar project.

Called BirdCast, a collaboration led by the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, the platform uses the same weather radar technology behind daily forecasts to track migrating birds.

On its live migration map, BirdCast tracked more than 1.2 billion birds streaming toward their wintering grounds after sunset on September 25—the largest single-night total recorded since the project began mapping live migrations in 2018.

“These numbers are almost inconceivable,” said Andrew Farnsworth, a visiting scientist at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology and longtime BirdCast researcher. “They’re enormous… even for people that study migration regularly. The scale of how many organisms that this represents, is just mind blowing.”

The surge surpasses the previous milestone of one billion birds, first observed during the migration in October 2023. Both included well over one hundred species flying toward warmer weather, including songbirds and shorebirds.

Farnsworth said this seemingly rare night captured about 10% of the continent’s birds in flight at the same time. On an average fall night during peak migration, about 400 million birds are detected in flight at the same time above the United States, but on this night, the number was three times that.

“It’s really unbelievable,” he said.

While astonishing to both birders and scientists, Farnsworth said this event was not random. It resulted from a combination of ideal migrating conditions coinciding with the peak of fall migration.

The weather that night was perfect for travel, he explained in a media release. It featured calm winds—including tail winds that helped push the birds along their migratory paths across much of the center of the country and the Mississippi River valley.

Farnsworth said this record-breaking migration—documented by radar technology that was never intended to track birds—is a chance to not only to marvel at the immense magnitude of bird migration but also a chance to remind the public that the data is freely available and accessible in real time.

The technology at BirdCast.org allows anyone to view forecast maps that predict the number of birds migrating while live migration maps show migration happening in real time. Both tools let people know when birds are moving nearby, so they can take necessary precautions to protect them.

“BirdCast gives the ability for more people to engage in and participate in this incredible spectacle,” Farnsworth said, whose Cornell Lab partners with three US universities in the project: Purdue, Illinois Urbana-Champaign, and Massachusetts Amherst.

It’s also a timely reminder that you can help make birds’ journeys safer. Every year, more than one billion birds die in collisions with windows in the United States.

Bright lights can disorient birds migrating at night, drawing them into areas where collisions with glass are common. To assist our feathered friends, turn off nonessential lights at night. You can also add bird friendly film or other markings on the outside of windows. Learn more at stopbirdcollisions.org. Record-Breaking Night of Bird Migration Caught on Radar During a ‘Perfect Storm’ for Feathered Flight

of the GSLV-D5 mission, however, is to flight-test the rocket’s all-important third stage: the indigenously-built cryogenic upper stage (CUS). The CUS, expected to be the mainstay of future GSLV flights, replaces the Russian cryogenic engine which was used in the rocket’s earlier experimental flights. There will be a lot of crossed fingers at Sriharikota during the launch, considering the new engine had a disastrous maiden flight in April 2010, shutting down less than a second after ignition, with the rocket plunging into the sea. The GSLV’s significance lies in the fact that the future of the global satellite market lies in the field of communications. The GSAT 14 satellite piggybacking the GSLV-D5 carries six Ku-band and six extended C-band transponders to help in digital audio broadcasting and other communications across the entire

of the GSLV-D5 mission, however, is to flight-test the rocket’s all-important third stage: the indigenously-built cryogenic upper stage (CUS). The CUS, expected to be the mainstay of future GSLV flights, replaces the Russian cryogenic engine which was used in the rocket’s earlier experimental flights. There will be a lot of crossed fingers at Sriharikota during the launch, considering the new engine had a disastrous maiden flight in April 2010, shutting down less than a second after ignition, with the rocket plunging into the sea. The GSLV’s significance lies in the fact that the future of the global satellite market lies in the field of communications. The GSAT 14 satellite piggybacking the GSLV-D5 carries six Ku-band and six extended C-band transponders to help in digital audio broadcasting and other communications across the entire subcontinent. Designed to last for a dozen years in its orbit, the satellite will replace the GSAT-3 (EDUSAT) which has been in orbit for 10 years. The big boosters in the GSLV series can hoist heavy communication satellites into geosynchronous orbits 36,000 km above the equator. In this position, the satellite keeps pace with Earth’s rotation and, as a result, appears stationary from the ground. This makes it easier to build simpler antennas on the ground, which do not have to track moving satellites in the sky. But powerful GSLV Mark IIIs (like the GSLV-D5) that can carry five-tonne satellites need cryogenic engines. These engines use fuels like oxygen and hydrogen in

subcontinent. Designed to last for a dozen years in its orbit, the satellite will replace the GSAT-3 (EDUSAT) which has been in orbit for 10 years. The big boosters in the GSLV series can hoist heavy communication satellites into geosynchronous orbits 36,000 km above the equator. In this position, the satellite keeps pace with Earth’s rotation and, as a result, appears stationary from the ground. This makes it easier to build simpler antennas on the ground, which do not have to track moving satellites in the sky. But powerful GSLV Mark IIIs (like the GSLV-D5) that can carry five-tonne satellites need cryogenic engines. These engines use fuels like oxygen and hydrogen in liquid form — stored at extremely low temperatures — to produce enormous amounts of thrust per unit mass (engineering parlance for the mass of fuel the engine requires to provide maximum thrust for a specific period such as, say, pounds of fuel per hour per pound of thrust). Rockets powered by cryogenic motors, therefore, need to carry much less fuel than would otherwise be required. Cryogenic fuels are also extremely clean as they give out only water while burning. A successful GSLV-D5 flight will make India only the sixth nation to possess this cutting edge technology, joining the United States, Russia, France, Japan and China in an elite club. India’s cryogenic

liquid form — stored at extremely low temperatures — to produce enormous amounts of thrust per unit mass (engineering parlance for the mass of fuel the engine requires to provide maximum thrust for a specific period such as, say, pounds of fuel per hour per pound of thrust). Rockets powered by cryogenic motors, therefore, need to carry much less fuel than would otherwise be required. Cryogenic fuels are also extremely clean as they give out only water while burning. A successful GSLV-D5 flight will make India only the sixth nation to possess this cutting edge technology, joining the United States, Russia, France, Japan and China in an elite club. India’s cryogenic motor development encountered some rough weather in 1993 when exaggerated US jitters — that India might utilise its space capabilities for military purposes — led to Moscow chickening out of a cryo-engine technology transfer deal with New Delhi. Of course, the real reason for guarding cryogenic engine technology so zealously probably had more to do with economics than national security. India’s arrival in the global heavy-lift launch market as a low cost launch source would have threatened the business interests of Europe, Russia, and the US. In hindsight, though, it seems to have been a disguised blessing for Indian scientists who were forced to develop

motor development encountered some rough weather in 1993 when exaggerated US jitters — that India might utilise its space capabilities for military purposes — led to Moscow chickening out of a cryo-engine technology transfer deal with New Delhi. Of course, the real reason for guarding cryogenic engine technology so zealously probably had more to do with economics than national security. India’s arrival in the global heavy-lift launch market as a low cost launch source would have threatened the business interests of Europe, Russia, and the US. In hindsight, though, it seems to have been a disguised blessing for Indian scientists who were forced to develop the technology on their own. The GSLV will reduce India’s dependence on foreign launchers like the ESA’s Ariane to launch INSAT-class satellites. Isro sources speak of plans to fly two more GSLVs at six-month-intervals before using the third one for the Chandrayaan-2 Moon mission. The GSLV-Mark III is also earmarked for launching human space flights in future and building orbiting space stations. Isro has built up an impressive portfolio of comparatively cheap space products and services that are attractive to foreign space agencies that want to outsource space missions. Together with the old workhorse Polar Satellite Launch Vehicle (PSLV), the GSLV can bolster

the technology on their own. The GSLV will reduce India’s dependence on foreign launchers like the ESA’s Ariane to launch INSAT-class satellites. Isro sources speak of plans to fly two more GSLVs at six-month-intervals before using the third one for the Chandrayaan-2 Moon mission. The GSLV-Mark III is also earmarked for launching human space flights in future and building orbiting space stations. Isro has built up an impressive portfolio of comparatively cheap space products and services that are attractive to foreign space agencies that want to outsource space missions. Together with the old workhorse Polar Satellite Launch Vehicle (PSLV), the GSLV can bolster India’s launch capability, which already boasts 30 to 35% cheaper launches than other countries. That said, however, the space agency cannot afford to ignore the fact that other players jostling in the international space market are constantly pushing the bar still higher. For the moment, though, all eyes will be on the GSLV-D5 mission, which will determine how soon Isro can claim its rightful share of the $300 billion global space market.

India’s launch capability, which already boasts 30 to 35% cheaper launches than other countries. That said, however, the space agency cannot afford to ignore the fact that other players jostling in the international space market are constantly pushing the bar still higher. For the moment, though, all eyes will be on the GSLV-D5 mission, which will determine how soon Isro can claim its rightful share of the $300 billion global space market.