What actually was the biggest dinosaur?

– Zavier, 14, Tauranga, New Zealand.

Great question Zavier, and one that palaeontologists (scientists who study fossil animals and plants) are interested in all around the world.

And let’s face it, kids of all ages (and I include adults here) are fascinated by dinosaurs that break records for the biggest, the longest, the scariest or the fastest. It’s why, to this day, one of most famous dinosaurs is still Tyranosaurus rex, the tyrant king.

These record-breaking dinosaurs are part of the reason why the Jurassic Park movie franchise has been so successful. Just think of the scene where Dr Alan Grant (played by New Zealand actor Sam Neill) is stunned by the giant sauropod dinosaur rearing up to reach the highest leaves in the tree with its long neck.

But how do scientists work out how big and heavy a dinosaur was? And what were the biggest dinosaurs that ever lived?

Calculating dinosaur size

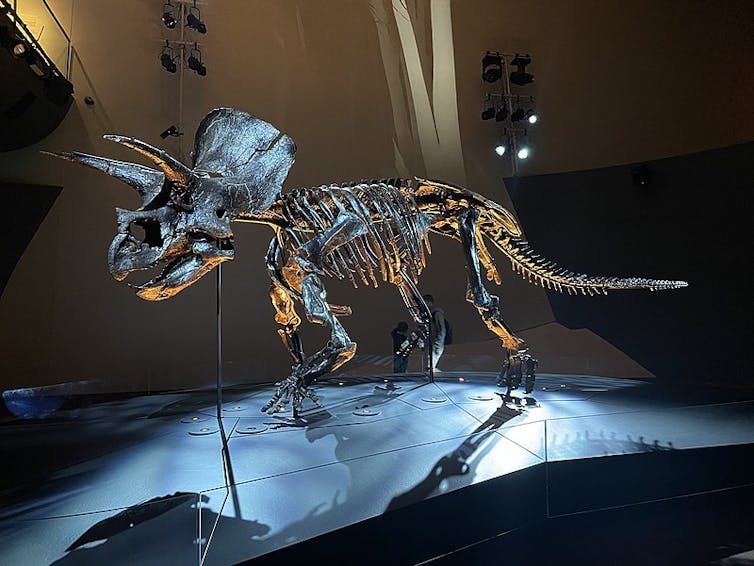

In an ideal world, calculating how big a dinosaur was would be easy – with a nearly complete skeleton. Standing next to the remarkable Triceratops skeleton on permanent display at Melbourne Museum makes you realise how gigantic and formidable these creatures were.

By measuring bone proportions (such as length, width or circumference) and plugging them into mathematical formulas and computer models, scientists can compare the measurements to those of living animals. They can then work out the likely size and weight of dinosaurs.

Calculating the size of dinosaurs is easy when you have near complete skeletons like this Triceratops at Melbourne Museum. Ginkgoales via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-NC-SA

Calculating the size of dinosaurs is easy when you have near complete skeletons like this Triceratops at Melbourne Museum. Ginkgoales via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-NC-SAEvery palaeontologist has their own favourite formula or computer model. Some are more accurate than others, which can lead to heated arguments!

In palaeontology, however, we are not always blessed with nearly complete skeletons. In a process called “taphonomy” – basically, what happens to the bones after an animal dies – dinosaur skeletons can be broken up and bones lost.

The more fragmented the remains of a dinosaur are, the more error is introduced into size and weight estimates.

Enter the titanosaurs

If we could travel back in time to South America during the Cretaceous period (about 143 million to 66 million years ago), we’d find a land ruled by a group of four-legged, long-necked and long-tailed, plant-eating sauropods. They would have towered over us, and the ground would shake with every step they took.

These were the titanosaurs. They reached their largest sizes during this period, before an asteroid crashed into what is now modern day Mexico 66 million years ago, making them extinct.

There are several contenders among the titanosaurs for the biggest dinosaur ever. Even the list below is controversial, with my palaeontology students pointing out several other possible contenders.

But based on six partial skeletons, the best estimate is for Patagotitan, which is thought to have been 31 meters long and to have weighed 50–57 tonnes.

A couple of others might have been as big or even bigger. Argentinosaurus has been calculated to be longer and heavier at 30–35 metres and 65–80 tonnes. And Puertasaurus was thought to be around 30 metres long and 50 tonnes.

But while the available bones of Argentinosaurus and Puertasaursus suggest reptiles of colossal size (the complete thigh bone of Argentinosaurus is 2.5 metres long!), there is currently not enough fossil material to be confident of those estimates.

Spinosaurus rules North Africa

An ocean away from South America’s titanosaurs, Spinosaurus lived in what is now North Africa during the Cretaceous period.

By a very small margin, Spinosaurus is currently thought to have been the largest carnivorous (meat-eating) dinosaur, weighing in at 7.4 tonnes and 14 meters long. Other Cretaceous giants are right up there, too, including Tyranosaurus rex from North America, Gigantosaurus from South America, and Carcharodontosaurus from North Africa.

Spinosaurus is unique among predatory dinosaurs in that it was semi-aquatic and had adapted to eating fish. You can see in the picture above how similar its skull shape was to a modern crocodile.

Palaeontology is now more popular than ever – maybe because of the ongoing Jurassic Park series – with a fossil “gold rush” occurring in the Southern Hemisphere.

Members of the public (known as “fossil forecasters”) are making new discoveries all the time.

So, who knows? The next discovery might turn out to be a new record holder as the biggest or longest dinosaur to have ever lived. There can be only one!

Hello curious kids! Do you have a question you’d like an expert to answer? Ask an adult to send your question to curiouskids@theconversation.edu.au![]()

Nic Rawlence, Associate Professor in Ancient DNA, University of Otago

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

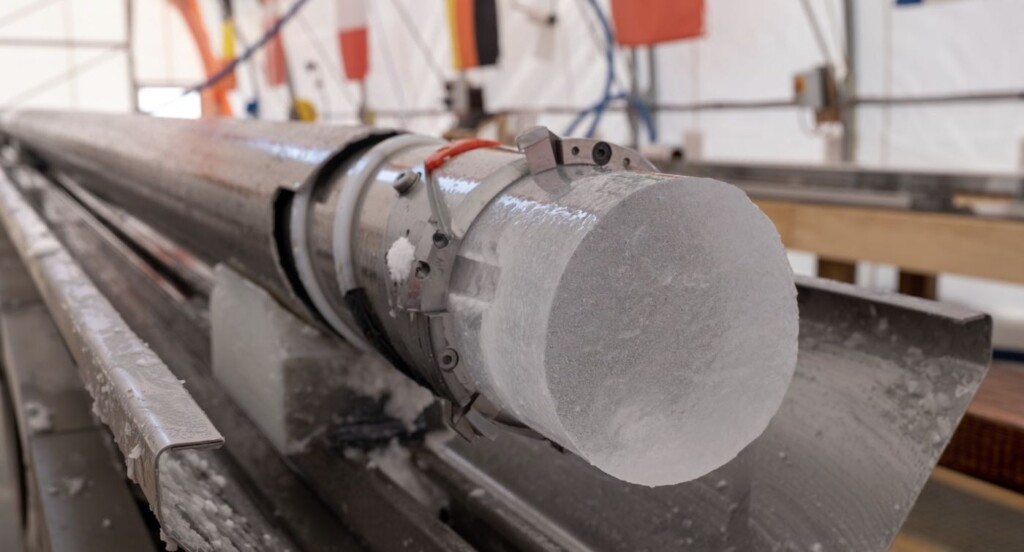

Antarctica ice core – PNRA / IPEV via SWNS

Antarctica ice core – PNRA / IPEV via SWNS Collecting and classifying ice core samples in Antarctic – PNRA / IPEV via SWNS

Collecting and classifying ice core samples in Antarctic – PNRA / IPEV via SWNS