59-year-old Man Who Had Type 2 Diabetes for 25 Years is Cured by Stem Cells

Ape Treating His Wound Using Medicinal Plant is a World First for a Wild Animal

Facial wound on adult male orangutan – Max Planck Institute of Animal Behavior via SWNS

Facial wound on adult male orangutan – Max Planck Institute of Animal Behavior via SWNS Rakus, 47 days after first treating the wound using the medicinal plant – Max Planck Institute of Animal Behavior via SWNS

Rakus, 47 days after first treating the wound using the medicinal plant – Max Planck Institute of Animal Behavior via SWNSScientists Studying Crows Get Big Surprise –They’re So Smart They Understand the Concept of Zero

Chuck Homler, DBA Focus on Wildlife/CC license 4.0

Chuck Homler, DBA Focus on Wildlife/CC license 4.0If size and frequency count, crickets may be the sexiest creatures

Susan Lawler, La Trobe University: If you had to guess what creature in the world had the largest testes, I doubt you would guess that the prize belonged to a cricket.

The testes of the tuberous bush cricket (Platycleis affinis) are an internal affair, taking up most of the cricket’s abdomen. At nearly 14% of their body weight, they are disproportionately large when compared to other species. Just think, a 100kg human would be walking around with 14kg of testicles, which would be mighty uncomfortable.

Why do these crickets need all that sperm power? It is because their females are highly promiscuous. The male bush crickets do not release more sperm than normal in any given sexual act, but they can be called upon to do it so often they apparently need the reserves. In the world of insects, it is not worth missing an opportunity, and if the females are going to be all available like that, then a cricket needs some world-class balls.

But this is not the only sexual record held by crickets. An Australian species known as scaly crickets (Ornebius aperta) have the most frequent sex of any species in the world. These little guys can do it more than 50 times in a few hours, often with the same female!

Why do they have to keep this up? Because she eats it.

That’s right, cricket sex provides more than the spark for the next generation. Males actually produce a package called a spermatophore, which is sperm wrapped up in a nutritious protein package. When the males insert it into a special opening in the females, sometimes she just bends down to gobble up her yummy post-coital snack.

Australian spiny cricket males respond to this sabotage by releasing only a few sperm per package, between 5 and 225 sperm per copulation, an astonishingly low amount compared to the average (100,000). Yet when researchers measured sperm loads in females, they had up to 20,000 sperm stored away. This means that they had sex up to 200 times to collect that amount.

Of course the females were storing up more than sperm. They also gathered nutrients that will help them develop eggs for the next generation. Other species of crickets manage the situation by offering a courtship gift in the form of food from the dorsal glands that distract the female and give her something to eat during sex.

Some female crickets seek out males in order to get these tasty gifts. A study of 32 different species of bushcrickets showed that the larger the spermatophore, the more likely the females were to actively seek out males. These gifts are costly to produce, so species that produce small spermatophores may mate twice a night, while those with large spermatophores may mate only once or twice in a lifetime.

The final cricket sex record goes to the Mormon cricket, which produces a spermatophore that is 27% of its body weight. That’s a huge investment in wild oats, which is a good description, since most of the package is food. The Mormon crickets are flightless and form swarms similar to locusts. These great walking hordes are often so hungry that cannibalism is common.

Female Mormon crickets will compete for males just so they can get a feed, and the benefit for the male is that some of his sperm may make it to the next generation.

Crickets are not likely to be overly loyal to each other, because research on Spanish field crickets shows that individuals with more mating partners leave more offspring. This applies to both male and female crickets, so it is surprising that males will nevertheless protect a female that they have mated with.

Male crickets will linger near a female they have recently given their sperm to, not to scare away other suitors, but to protect the female from predators. He does this at his own peril, because males that hang about after sex are four times more likely to be eaten. On the other hand, the females are six times less likely to be eaten if he is there to protect her.

Male crickets are not confused about the goal of spermatophore transfer. But female crickets want more than just sperm from their partner. A meal (or several dozen meals) increases the male cricket’s chance of getting lucky.

Maybe they are not so different from people, after all. ![]()

Susan Lawler, Head of Department, Department of Environmental Management & Ecology, La Trobe University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

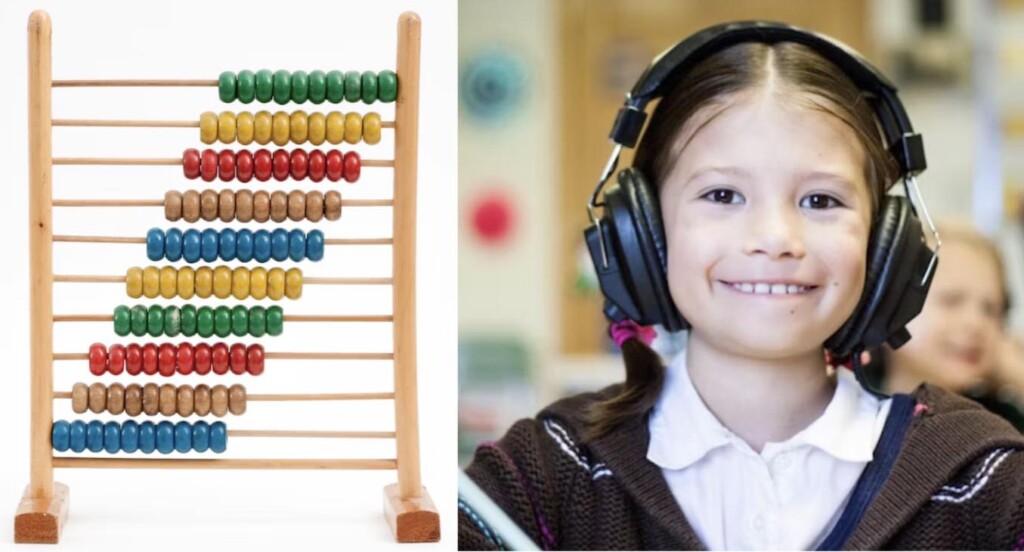

Children Do Much Better in Math When Music is Added to the Lesson: New Study

Photos by Crissy Jarvis (left) and Ben Mullins

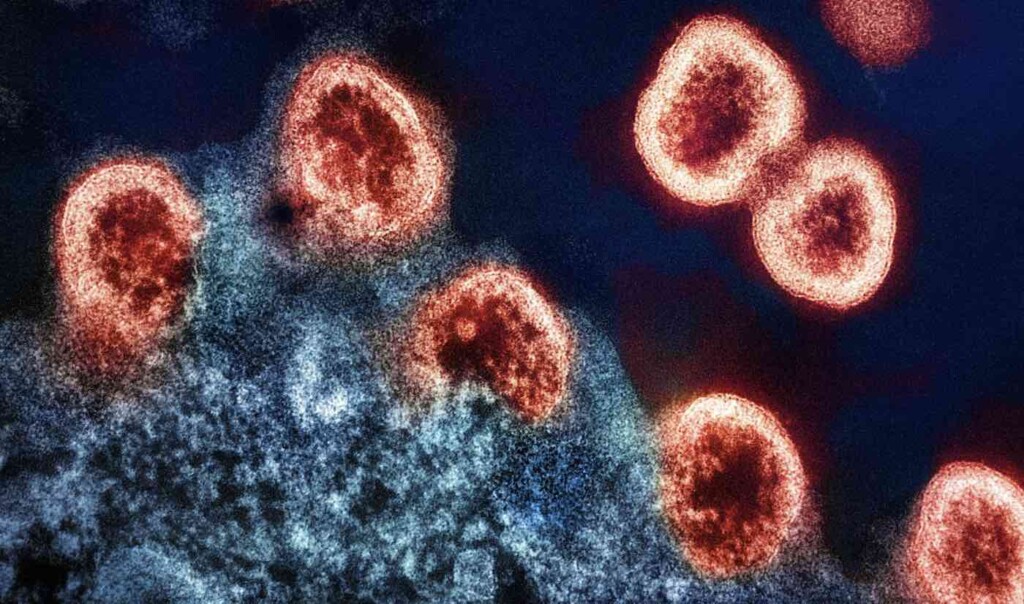

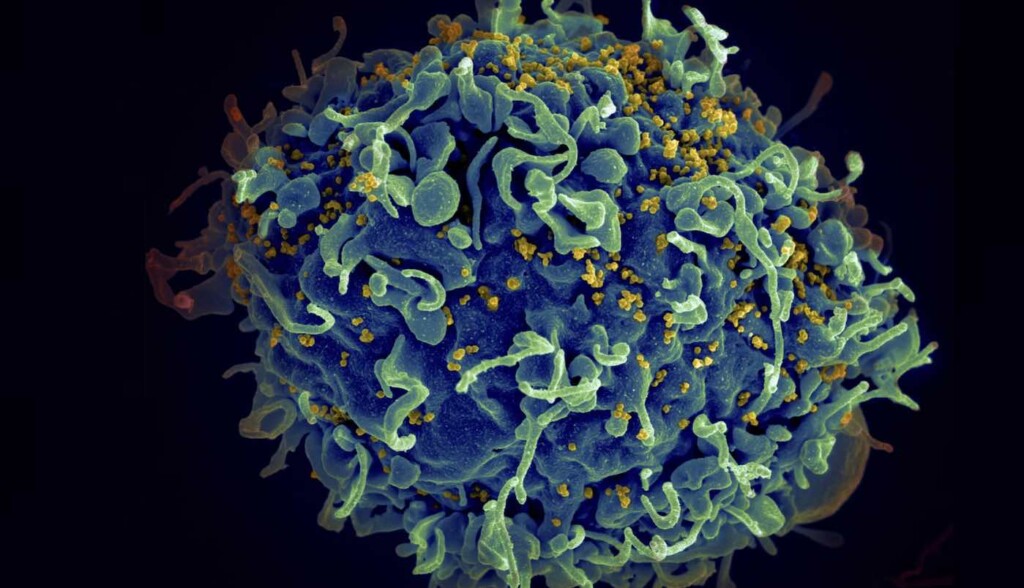

Photos by Crissy Jarvis (left) and Ben MullinsScientists Discover Potential HIV Cure that Eliminates Disease from Cells Using CRISPR-Cas Gene Editing

HIV-1 virus particles under electron micrograph with H9 T-cells (in blue) – Credit: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases

HIV-1 virus particles under electron micrograph with H9 T-cells (in blue) – Credit: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases

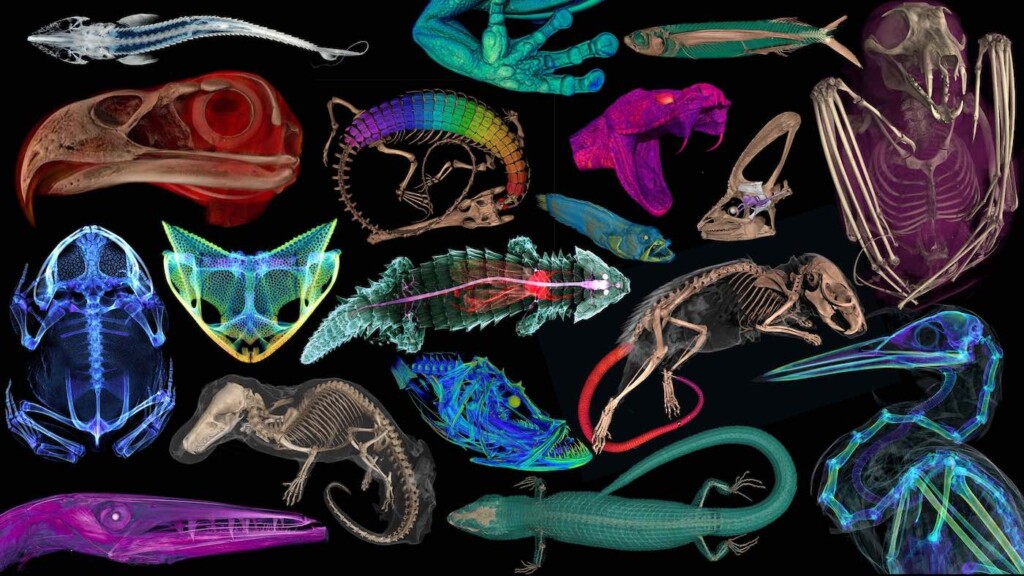

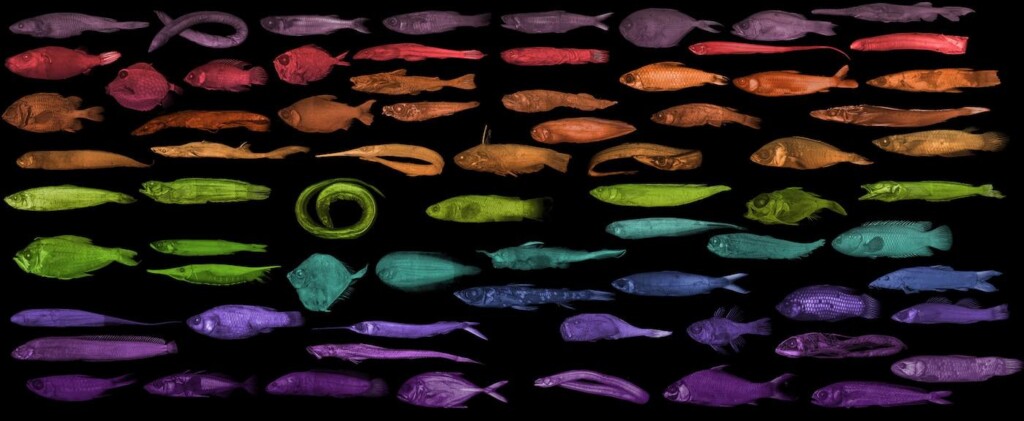

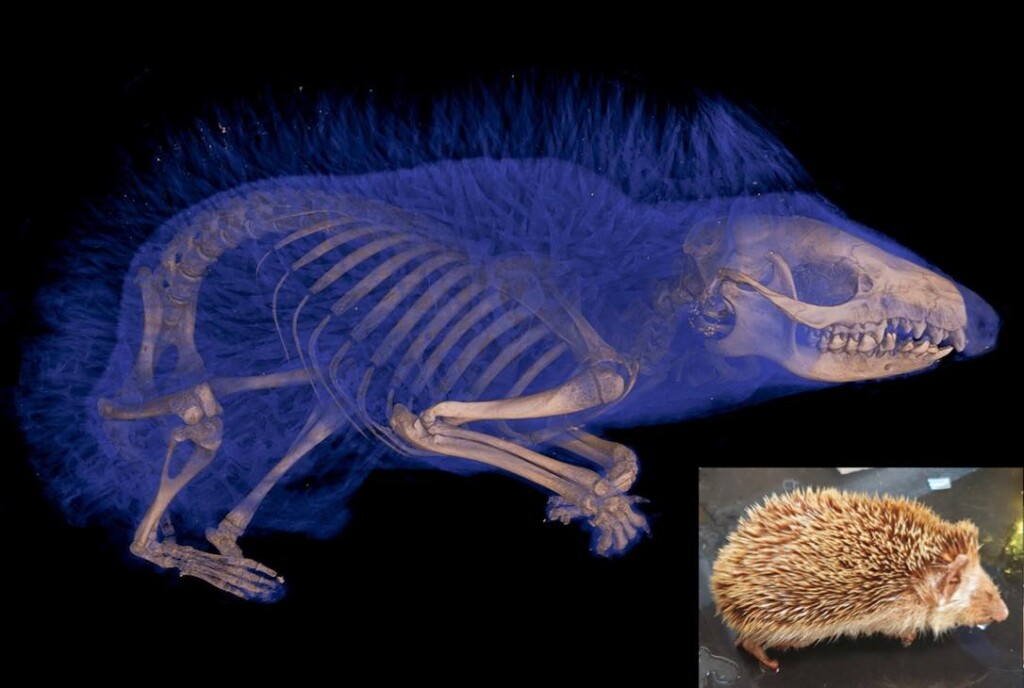

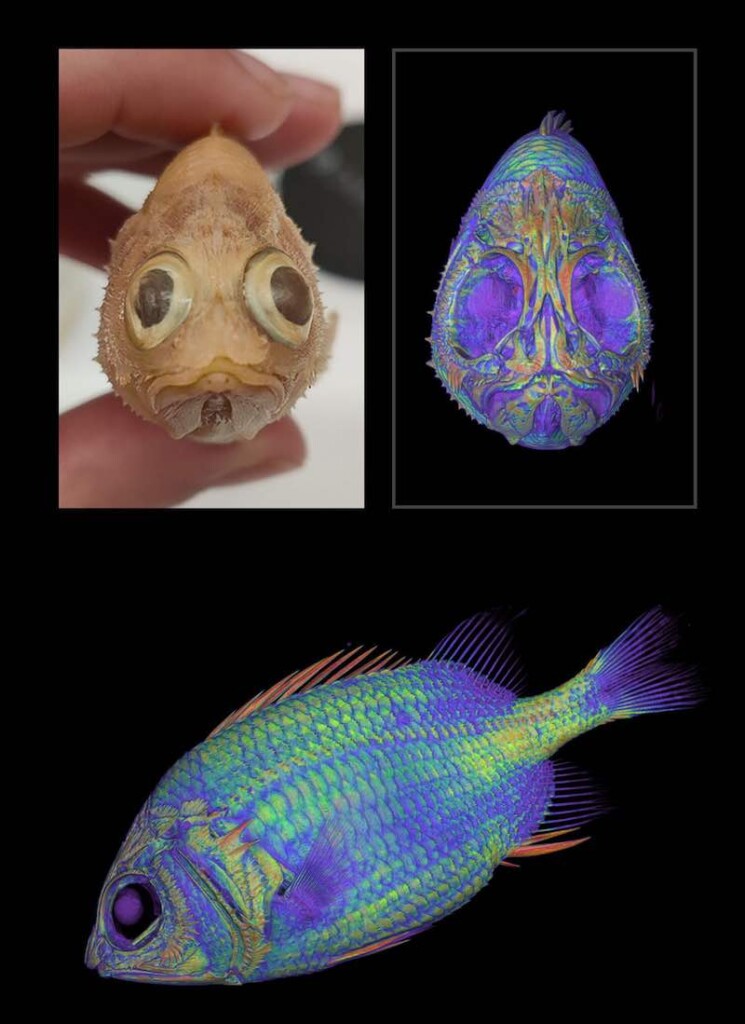

Scientists Have 3D-Scanned Thousands of Creatures Creating Incredibly Intricate Images Anyone Can Access for Free

'Love hormone' guides young songbirds in choice of 'voice coach'

Zebra finches are highly social birds and will press a lever in order to hear a recording of another Zebra finch singing. (Photo by Carlos Rodríguez-Saltos)

Zebra finches are highly social birds and will press a lever in order to hear a recording of another Zebra finch singing. (Photo by Carlos Rodríguez-Saltos)Scientists studied twins’ diets. Those who ate vegan saw fast results.

A member of staff works inside ‘Rudy’s Vegan Butcher’ shop, amid the coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak, in London, Britain, October 30, 2020. Picture taken October 30, 2020. REUTERS/Henry Nicholls

A member of staff works inside ‘Rudy’s Vegan Butcher’ shop, amid the coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak, in London, Britain, October 30, 2020. Picture taken October 30, 2020. REUTERS/Henry NichollsResearchers found 37 mine sites in Australia that could be converted into renewable energy storage. So what are we waiting for?

Shutterstock

Timothy Weber, Australian National University and Andrew Blakers, Australian National University

Shutterstock

Timothy Weber, Australian National University and Andrew Blakers, Australian National UniversityThe world is rapidly moving towards a renewable energy future. To support the transition, we must prepare back-up energy supplies for times when solar panels and wind turbines are not producing enough electricity.

One solution is to build more pumped hydro energy storage. But where should this expansion happen?

Our new research identified more than 900 suitable locations around the world: at former and existing mining sites. Some 37 sites are in Australia.

Huge open-cut mining pits would be turned into reservoirs to hold water for renewable energy storage. It would give the sites a new lease on life and help shore up the world’s low-emissions future.

The benefits of pumped hydro storage

Pumped hydro energy storage has been demonstrated at scale for more than a century. Over the past few years, we have been identifying the best sites for “closed-loop” pumped hydro systems around the world.

Unlike conventional hydropower systems operating on rivers, closed-loop systems are located away from rivers. They require only two reservoirs, one higher than the other, between which water flows down a tunnel and through a turbine, producing electricity.

The water can be released – and power produced – to cover gaps in electricity supply when output from solar and wind is low (for example on cloudy or windless days). And when wind and solar are producing more electricity than is needed – such as on sunny or windy days – this cheap surplus power is used to pump the water back up the hill to the top reservoir, ready to be released again.

Off-river sites have very small environmental footprints and require very little water to operate. Pumped hydro energy storage is also generally cheaper than battery storage at large scales.

Batteries are the preferred method for energy storage over seconds to hours, while pumped hydro is preferred for overnight and longer storage.

Pumped-hydro storage technology has been demonstrated at scale for over a century. Shutterstock

Pumped-hydro storage technology has been demonstrated at scale for over a century. ShutterstockWhy mining sites?

There are big benefits to converting mining areas into pumped hydro plants.

For a start, the hole has already been dug, reducing construction costs. What’s more, mining sites are typically already serviced by roads and transmission infrastructure. The site usually has access to a water source for which the mine operators may have pumping rights. And the development takes place on land that is already cleared of vegetation, avoiding the need to disturb new areas.

Finally, community support may have already been obtained for the mining operations, which could easily be rolled over into a pumped hydro site.

In Australia, one pumped hydro energy storage project is already being built at a former gold mine site at Kidston in Far North Queensland.

The feasibility of two others is being assessed at Mount Rawdon near Bundaberg in Queensland, and at Muswellbrook in New South Wales. Both would repurpose old mining pits.

What we found

Our previous research identified suitable locations in undeveloped areas (excluding protected land) and using existing reservoirs. Now, we have turned our attention to mine sites.

Our study used a computer algorithm to search the Earth’s surface for suitable sites. It looked for mining pits, pit lakes and tailings ponds in mining sites which were located near suitable land for a new upper reservoir. The idea is that the reservoir and mining site are “paired” and water pumped between them.

Globally, we identified 904 suitable mining sites across 77 countries.

Some 37 suitable sites are located in Australia. They include the Mount Rawdon and Muswellbrook mining pits already under investigation.

There are a number of potential options in Western Australia: in the iron-ore region of the Pilbara, south of Perth and around Kalgoorlie.

Options in Queensland and New South Wales are mostly located down the east coast, including the Coppabella Mine and the coal mining pits near the old Liddell Power Station. Possible sites also exist inland at Mount Isa in Queensland and at the Cadia Hill gold mine near Orange in NSW.

Potential sites in South Australia include the old Leigh Creek coal mine in the Flinders Ranges and the operating Prominent Hill mine northwest of Adelaide. Tasmania and Victoria also offer possible locations, although many other non-mining options exist in these states for pumped hydro storage.

We are not suggesting that operating mines be closed – rather, that pumped hydro storage be considered as part of site rehabilitation at the end of the mine’s life.

If old mining sites are to be converted into pumped hydro, several challenges must be addressed. For example, mine pits may contain contaminants that, if filled with water, could seep into groundwater. However, this could be overcome by lining reservoirs.

Looking ahead

Australia has set a readily achievable goal of reaching 82% renewable electricity by 2030.

The Australian Energy Market Operator suggests by 2050, this nation needs about 640 gigawatt-hours of dispatchable or “on demand” storage to support solar and wind capacity. We currently have about 17 gigawatt-hours of electricity storage, with more committed by Snowy 2.0 and other projects.

The 37 possible pumped hydro sites we’ve identified could deliver 540 gigawatt-hours of storage potential. Combined with other non-mining sites we’ve identified previously, the options are far more numerous than our needs.

This means we can afford to be picky, and develop only the very best sites. So what are we waiting for?![]()

Timothy Weber, Research Officer for School of Engineering, Australian National University and Andrew Blakers, Professor of Engineering, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Think you’re good at multi-tasking? Here’s how your brain compensates – and how this changes with age

Arlington Research/Unsplash Peter Wilson, Australian Catholic UniversityWe’re all time-poor, so multi-tasking is seen as a necessity of modern living. We answer work emails while watching TV, make shopping lists in meetings and listen to podcasts when doing the dishes. We attempt to split our attention countless times a day when juggling both mundane and important tasks.

Arlington Research/Unsplash Peter Wilson, Australian Catholic UniversityWe’re all time-poor, so multi-tasking is seen as a necessity of modern living. We answer work emails while watching TV, make shopping lists in meetings and listen to podcasts when doing the dishes. We attempt to split our attention countless times a day when juggling both mundane and important tasks.

But doing two things at the same time isn’t always as productive or safe as focusing on one thing at a time.

The dilemma with multi-tasking is that when tasks become complex or energy-demanding, like driving a car while talking on the phone, our performance often drops on one or both.

Here’s why – and how our ability to multi-task changes as we age.

Doing more things, but less effectively

The issue with multi-tasking at a brain level, is that two tasks performed at the same time often compete for common neural pathways – like two intersecting streams of traffic on a road.

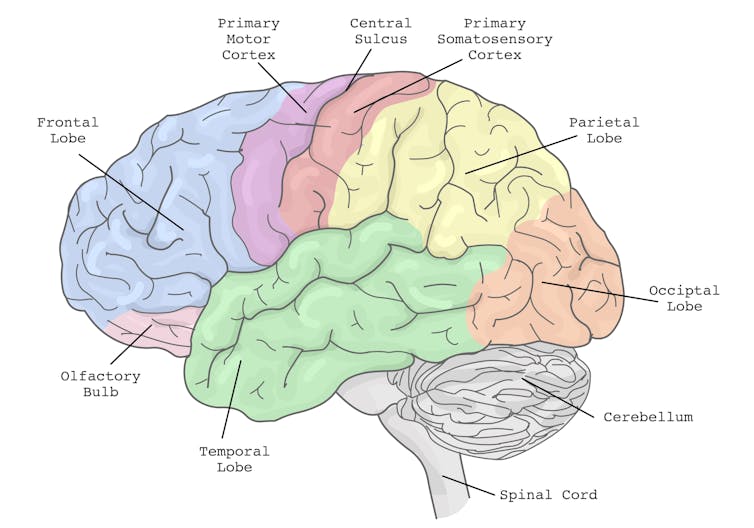

In particular, the brain’s planning centres in the frontal cortex (and connections to parieto-cerebellar system, among others) are needed for both motor and cognitive tasks. The more tasks rely on the same sensory system, like vision, the greater the interference.

The brain’s action planning centres are in the frontal cortex (blue), with reciprocal connections to parietal cortex (yellow) and the cerebellum (grey), among others. grayjay/Shutterstock

The brain’s action planning centres are in the frontal cortex (blue), with reciprocal connections to parietal cortex (yellow) and the cerebellum (grey), among others. grayjay/ShutterstockThis is why multi-tasking, such as talking on the phone, while driving can be risky. It takes longer to react to critical events, such as a car braking suddenly, and you have a higher risk of missing critical signals, such as a red light.

The more involved the phone conversation, the higher the accident risk, even when talking “hands-free”.

Having a conversation while driving slows your reaction time. GBJSTOCK/Shutterstock

Having a conversation while driving slows your reaction time. GBJSTOCK/ShutterstockGenerally, the more skilled you are on a primary motor task, the better able you are to juggle another task at the same time. Skilled surgeons, for example, can multitask more effectively than residents, which is reassuring in a busy operating suite.

Highly automated skills and efficient brain processes mean greater flexibility when multi-tasking.

Adults are better at multi-tasking than kids

Both brain capacity and experience endow adults with a greater capacity for multi-tasking compared with children.

You may have noticed that when you start thinking about a problem, you walk more slowly, and sometimes to a standstill if deep in thought. The ability to walk and think at the same time gets better over childhood and adolescence, as do other types of multi-tasking.

When children do these two things at once, their walking speed and smoothness both wane, particularly when also doing a memory task (like recalling a sequence of numbers), verbal fluency task (like naming animals) or a fine-motor task (like buttoning up a shirt). Alternately, outside the lab, the cognitive task might fall by wayside as the motor goal takes precedence.

Brain maturation has a lot to do with these age differences. A larger prefrontal cortex helps share cognitive resources between tasks, thereby reducing the costs. This means better capacity to maintain performance at or near single-task levels.

The white matter tract that connects our two hemispheres (the corpus callosum) also takes a long time to fully mature, placing limits on how well children can walk around and do manual tasks (like texting on a phone) together.

For a child or adult with motor skill difficulties, or developmental coordination disorder, multi-tastking errors are more common. Simply standing still while solving a visual task (like judging which of two lines is longer) is hard. When walking, it takes much longer to complete a path if it also involves cognitive effort along the way. So you can imagine how difficult walking to school could be.

What about as we approach older age?

Older adults are more prone to multi-tasking errors. When walking, for example, adding another task generally means older adults walk much slower and with less fluid movement than younger adults.

These age differences are even more pronounced when obstacles must be avoided or the path is winding or uneven.

Our ability to multi-task reduces with age. Shutterstock/Grizanda

Our ability to multi-task reduces with age. Shutterstock/GrizandaOlder adults tend to enlist more of their prefrontal cortex when walking and, especially, when multi-tasking. This creates more interference when the same brain networks are also enlisted to perform a cognitive task.

These age differences in performance of multi-tasking might be more “compensatory” than anything else, allowing older adults more time and safety when negotiating events around them.

Older people can practise and improve

Testing multi-tasking capabilities can tell clinicians about an older patient’s risk of future falls better than an assessment of walking alone, even for healthy people living in the community.

Testing can be as simple as asking someone to walk a path while either mentally subtracting by sevens, carrying a cup and saucer, or balancing a ball on a tray.

Patients can then practise and improve these abilities by, for example, pedalling an exercise bike or walking on a treadmill while composing a poem, making a shopping list, or playing a word game.

The goal is for patients to be able to divide their attention more efficiently across two tasks and to ignore distractions, improving speed and balance.

There are times when we do think better when moving

Let’s not forget that a good walk can help unclutter our mind and promote creative thought. And, some research shows walking can improve our ability to search and respond to visual events in the environment.

But often, it’s better to focus on one thing at a time

We often overlook the emotional and energy costs of multi-tasking when time-pressured. In many areas of life – home, work and school – we think it will save us time and energy. But the reality can be different.

Multi-tasking can sometimes sap our reserves and create stress, raising our cortisol levels, especially when we’re time-pressured. If such performance is sustained over long periods, it can leave you feeling fatigued or just plain empty.

Deep thinking is energy demanding by itself and so caution is sometimes warranted when acting at the same time – such as being immersed in deep thought while crossing a busy road, descending steep stairs, using power tools, or climbing a ladder.

So, pick a good time to ask someone a vexed question – perhaps not while they’re cutting vegetables with a sharp knife. Sometimes, it’s better to focus on one thing at a time.![]()

Peter Wilson, Professor of Developmental Psychology, Australian Catholic University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Polar bears may struggle to produce milk for their cubs as climate change melts sea ice

During their time onshore, polar bear mothers may risk their survival by continuing to nurse when food is not available. (Shutterstock)

Louise Archer, University of Toronto

During their time onshore, polar bear mothers may risk their survival by continuing to nurse when food is not available. (Shutterstock)

Louise Archer, University of TorontoWhen sea ice melts, polar bears must move onto land for several months without access to food. This fasting period is challenging for all bears, but particularly for polar bear mothers who are nursing cubs.

Our research, published in Marine Ecology Progress Series, found that polar bear lactation is negatively affected by increased time spent on land when sea ice melts.

Impaired lactation has likely played a role in the recent decline of several polar bear populations. This research also indicates how polar bear families might be impacted in the future by continued sea-ice loss caused by climate warming.

Challenges of rearing cubs

While sea ice might appear as a vast and perhaps vacant ecosystem, the frozen Arctic waters provide an essential platform for polar bears to hunt energy-rich seals — the bread and butter of their diet.

On shore, polar bears often remain in a fasting state, using their body stores of fat for fuel. (Shutterstock)

On shore, polar bears often remain in a fasting state, using their body stores of fat for fuel. (Shutterstock)While on shore, hunting opportunities are rare and polar bears generally spend their time in a fasting state. Polar bears rely on their immense body fat stores to fuel them during these leaner months, with some individuals measuring almost 50 per cent body fat when they come onshore in early summer.

While on land, polar bears can lose around a kilogram of body mass per day, so making it to the end of the ice-free season requires them to carefully manage their energy. For most polar bears, this means reducing activity levels and conserving energy until the sea ice returns and seal hunting can resume.

Females with cubs must also factor in the additional burden of lactation. Polar bears produce high-energy milk, which — at up to 35 per cent fat — is like whipping cream. This high-fat milk allows cubs to grow quickly, increasing from just 600 grams at birth to well over 100 kilograms by the time they are around two-and-a-half years old and leave their mothers to become independent.

Although lactation is important to both mothers and cubs, studies on polar bear lactation are relatively rare.

To better understand how females manage their lactation investment, our research team revisited a data set of polar bear milk samples collected in the late 1980s and early 1990s from polar bears on land during the ice-free period.

We estimated how long each polar bear mom had been fasting based on annual sea-ice breakup dates and found that the energy content of their milk declined the more days spent onshore. Some bears had stopped producing milk entirely. Both milk energy content and lactation probability were negatively related to the mother’s body condition, meaning females in poor body condition had to prioritize their own energetic needs over their cubs.

The bears who reduced their investment in lactation benefited by using up less of their body reserves, meaning they could fast for longer. Yet the cubs who received lower energy milk grew more slowly than offspring of females that maintained their lactation effort. In the long term, this may reduce cub survival and, ultimately, negatively affect population dynamics.

Climate change and population declines

After around three months on land, the probability of a female with cubs lactating was 53 per cent. This dropped to 35 per cent for a female with yearlings (older cubs from the previous year).

The data in our study were collected around three decades ago. Since then, climate warming has meant that the ice-free season in western Hudson Bay has been extending by around seven days per decade. Polar bears are now regularly forced to spend more than four months on land.

As the ice-free season has increased and polar bears must go for longer without food, their average body condition has declined. The ability of female polar bears to nurse their cubs has probably also become increasingly impaired.

This may have contributed to the 50 per cent decline in the population size of the western Hudson Bay population over the last four decades, and is likely to contribute to further declines if climate warming and sea-ice declines continue as projected without mitigation.

This research adds another piece to our understanding of polar bear resilience to climate change. Without action to halt climate warming and sea-ice loss, survival of cubs will be at risk across the Arctic.![]()

Louise Archer, Postdoctoral Fellow, Biological Sciences, University of Toronto

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Is it normal to forget words while speaking? And when can it spell a problem?

mimi thian/unsplash Greig de Zubicaray, Queensland University of TechnologyWe’ve all experienced that moment mid-sentence when we just can’t find the word we want to use, even though we’re certain we know it.

mimi thian/unsplash Greig de Zubicaray, Queensland University of TechnologyWe’ve all experienced that moment mid-sentence when we just can’t find the word we want to use, even though we’re certain we know it.Why does this universal problem among speakers happen?

And when can word-finding difficulties indicate something serious?

Everyone will experience an occasional word-finding difficulty, but if they happen very often with a broad range of words, names and numbers, this could be a sign of a neurological disorder.

The steps involved in speaking

Producing spoken words involves several stages of processing.

These include:

identifying the intended meaning

selecting the right word from the “mental lexicon” (a mental dictionary of the speaker’s vocabulary)

retrieving its sound pattern (called its “form”)

executing the movements of the speech organs for articulating it.

Word-finding difficulties can potentially arise at each of these stages of processing.

When a healthy speaker can’t retrieve a word from their lexicon despite the feeling of knowing it, this is called a “tip-of-the-tongue” phenomenon by language scientists.

Often, the frustrated speaker will try to give a bit of information about their intended word’s meaning, “you know, that thing you hit a nail with”, or its spelling, “it starts with an H!”.

Tip-of-the-tongue states are relatively common and are a type of speech error that occurs primarily during retrieval of the sound pattern of a word (step three above).

What can affect word finding?

Word-finding difficulties occur at all ages but they do happen more often as we get older. In older adults, they can cause frustration and anxiety about the possibility of developing dementia. But they’re not always a cause for concern.

One way researchers investigate word-finding difficulties is to ask people to keep a diary to record how often and in what context they occur. Diary studies have shown that some word types, such as names of people and places, concrete nouns (things, such as “dog” or “building”) and abstract nouns (concepts, such as “beauty” or “truth”), are more likely to result in tip-of-the-tongue states compared with verbs and adjectives.

Less frequently used words are also more likely to result in tip-of-the-tongue states. It’s thought this is because they have weaker connections between their meanings and their sound patterns than more frequently used words.

Laboratory studies have also shown tip-of-the-tongue states are more likely to occur under socially stressful conditions when speakers are told they are being evaluated, regardless of their age. Many people report having experienced tip-of-the-tongue problems during job interviews.

When could it spell more serious issues?

More frequent failures with a broader range of words, names and numbers are likely to indicate more serious issues.

When this happens, language scientists use the terms “anomia” or “anomic aphasia” to describe the condition, which can be associated with brain damage due to stroke, tumours, head injury or dementia such as Alzheimer’s disease.

Recently, the actor Bruce Willis’s family revealed he has been diagnosed with a degenerative disorder known as primary progressive aphasia, for which one of the earliest symptoms is word-finding difficulties rather than memory loss.

Primary progressive aphasia is typically associated with frontotemporal or Alzheimer’s dementias, although it can be associated with other pathologies.

Anomic aphasia can arise due to problems occurring at different stages of speech production. An assessment by a clinical neuropsychologist or speech pathologist can help clarify which processing stage is affected and how serious the problem might be.

For example, if a person is unable to name a picture of a common object such as a hammer, a clinical neuropsychologist or speech pathologist will ask them to describe what the object is used for (the individual might then say “it’s something you hit things with” or “it’s a tool”).

If they can’t, they will be asked to gesture or mime how it’s used. They might also be provided with a cue or prompt, such as the first letter (h) or syllable (ham).

Most people with anomic aphasia benefit greatly from being prompted, indicating they are mostly experiencing problems with later stages of retrieving word forms and motor aspects of speech.

But if they’re unable to describe or mime the object’s use, and cueing does not help, this is likely to indicate an actual loss of word knowledge or meaning. This is typically a sign of a more serious issue such as primary progressive aphasia.

Imaging studies in healthy adults and people with anomic aphasia have shown different areas of the brain are responsible for their word-finding difficulties.

In healthy adults, occasional failures to name a picture of a common object are linked with changes in activity in brain regions that control motor aspects of speech, suggesting a spontaneous problem with articulation rather than a loss of word knowledge.

In anomia due to primary progressive aphasia, brain regions that process word meanings show a loss of nerve cells and connections or atrophy.

Although anomic aphasia is common after strokes to the left hemisphere of the brain, the associated word-finding difficulties do not appear to be distinguishable by specific areas.

There are treatments available for anomic aphasia. These will often involve speech pathologists training the individual on naming tasks using different kinds of cues or prompts to help retrieve words. The cues can be various meaningful features of objects and ideas, or sound features of words, or a combination of both. Smart tablet and phone apps also show promise when used to complement therapy with home-based practice.

The type of cue used for treatment is determined by the nature of the person’s impairment. Successful treatment is associated with changes in activity in brain regions known to support speech production. Unfortunately, there is no effective treatment for primary progressive aphasia, although some studies have suggested speech therapy can produce temporary benefits.

If you’re concerned about your word-finding difficulties or those of a loved one, you can consult your GP for a referral to a clinical neuropsychologist or a speech pathologist. ![]()

Greig de Zubicaray, Professor of Neuropsychology, Queensland University of Technology

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

How consciousness may rely on brain cells acting collectively – new psychedelics research on rats

Pär Halje, Associate Research Fellow of Neurophysiology, Lund University This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Pär Halje, Associate Research Fellow of Neurophysiology, Lund University This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.