Sasun Bughdaryan/Unsplash

Carolyn Nickson, University of Sydney; The University of Melbourne and Bruce Mann, The University of Melbourne

Sasun Bughdaryan/Unsplash

Carolyn Nickson, University of Sydney; The University of Melbourne and Bruce Mann, The University of MelbourneAt least 20,000 Australian women are diagnosed with breast cancer each year. And more than 3,300 die from the disease.

To save women’s lives, we need to detect breast cancer early. Breast screening, which halves women’s risk of dying from breast cancer, is key to that.

A new Australian study published today in The Lancet Digital Health suggests AI could help improve how we screen for breast cancer.

How do we currently screen for breast cancer?

Since 1992, Australia has offered free breast X-rays, known as mammograms, every two years to women aged between 50 and 74. Just over half of eligible women participate.

Of the women found to have cancer, about 25% are diagnosed between the biennial screens. These “interval cancers” are often aggressive and, unfortunately, more likely to be fatal.

In some cases, a more sensitive screening test may have detected them earlier.

The role of AI

Australia’s BreastScreen program was established in response to several major clinical trials conducted between the 1960s and 1980s. The screening technology used by the program has not substantially changed since then.

Researchers are now exploring risk-adjusted screening, which tailors screening to women based on their risk, as a way to detect more cancers earlier. This may include programs offering different technologies for women at higher risk of developing breast cancer.

Currently, we generally assess cancer risk via questionnaires that help identify if a woman has any risk factors associated with breast cancer.

One risk factor is breast density which refers to how much glandular tissue is in the breast. As well as being a risk factor for breast cancer, the higher a woman’s breast density, the harder it is to detect cancer on a mammogram.

We can also use one-off genetic testing to identify women with a higher lifetime risk of developing breast cancer. This involves looking for high-risk gene mutations such as BRCA1 and BRCA2, which are associated with increased breast and ovarian cancer risk. Genetic testing can also help us estimate a person’s lifetime risk of developing breast cancer.

More recently, researchers have been investigating artificial intelligence (AI) as a new approach to assess breast cancer risk. A new Australian study, published in The Lancet Digital Health today, focused on a specific AI tool known as BRAIx.

What did the study involve? And what did it find?

This study used an AI tool, known as BRAIx, trained using BreastScreen Australia data to help radiologists assess mammograms.

The study assessed how well BRAIx predicted women’s risk of developing breast cancer in the next four years, among women who had a clear mammogram.

Of the 95,823 Australian women assessed, 1.1% (1,098) had developed breast cancer in the four years after they received a clear mammogram. Of the 4,430 Swedish women assessed, 6.9% had developed breast cancer within two years of a clear screen.

The study findings show that BRAIx scores were very useful for identifying women who were more likely to develop cancer one to two years after having a clear screen. Findings from the Australian dataset suggest BRAIx scores identified cancers found three to four years later, but with less accuracy.

These findings suggest BRAIx could help identify women who might benefit from additional tests. This may include an MRI (which uses a magnetic field to produce images of organs and tissue) or contrast-enhanced mammography (which uses an iodine dye to improve the visibility of a regular mammogram).

These findings reinforce a 2024 Swedish study that used an AI-based risk assessment to select women for additional testing. The researchers referred 7% of women to have a follow-up MRI, and 6.5% of were found to have cancers missed by mammograms.

Does the study have any limitations?

As with most studies, yes. Here are two.

it’s difficult to compare BRAIx to genetic testing. This is because BRAIx is trained to find missed or emerging cancers over a four year period. In contrast, genetic testing identifies a person’s risk of developing cancer over their lifetime

it might not use the best breast density data. This study found BRAIx more accurately predicts breast cancer risk compared to assessments based on breast density. But this breast density data was collected using a different tool to those used by the Breastscreen program. So this finding should be interpreted carefully.

So, where to from here?

The study adds to a growing body of evidence that AI risk assessment could help breast screening programs find cancers earlier.

BRAIx is now being trialled as part of the BreastScreen Victoria program, to help read mammograms. And other states are already using and evaluating different AI tools for reading mammograms.

So it may be time for Australia to conduct a national, independent review of these new tools. As part of a more risk-adjusted approach to breast screening, they could save lives.![]()

Carolyn Nickson, Principal Research Fellow, Cancer Elimination Collaboration, University of Sydney; The University of Melbourne and Bruce Mann, Professor of Surgery, Specialist Breast Surgeon, The University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

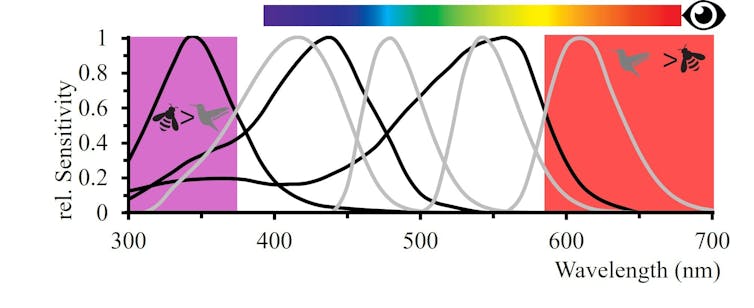

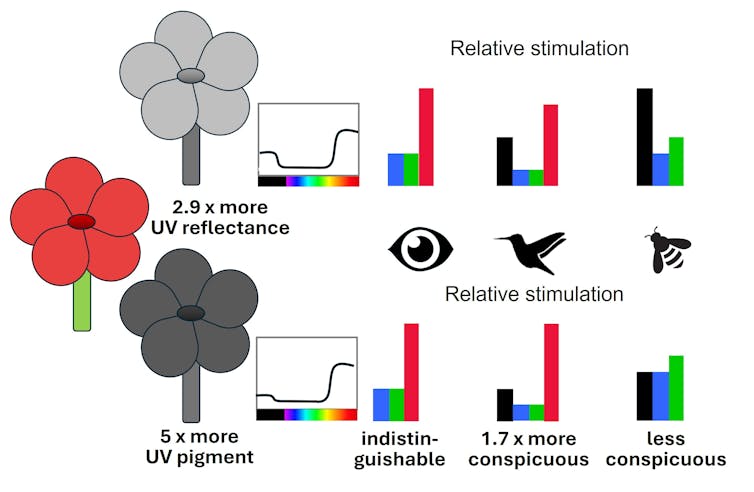

Most red flowers are visited by birds, rather than bees.

Most red flowers are visited by birds, rather than bees.

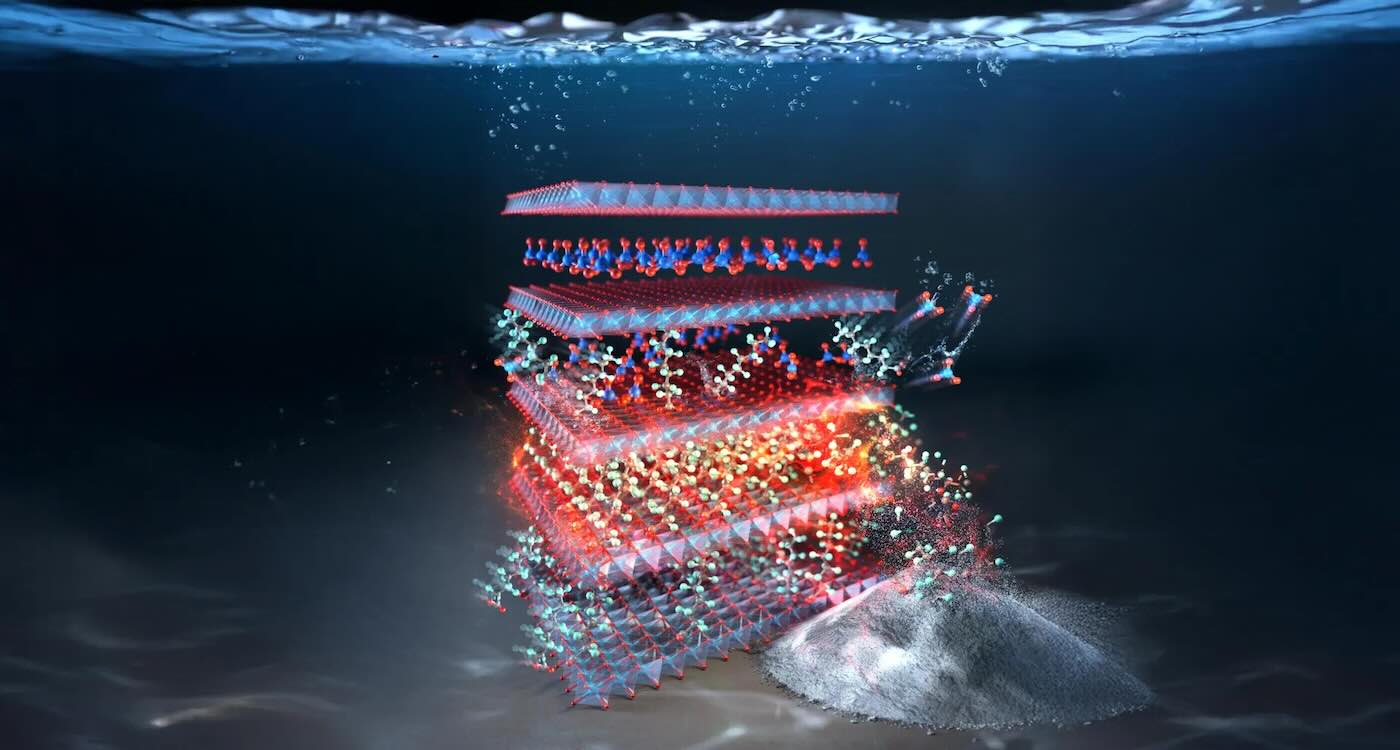

_15595.jpg) (Image: INL)

(Image: INL)