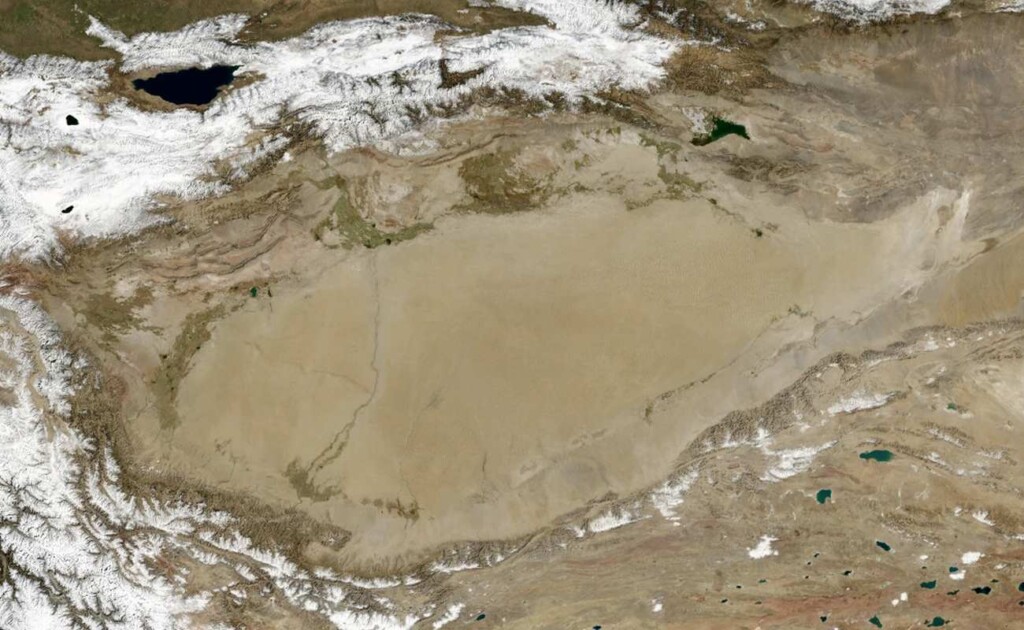

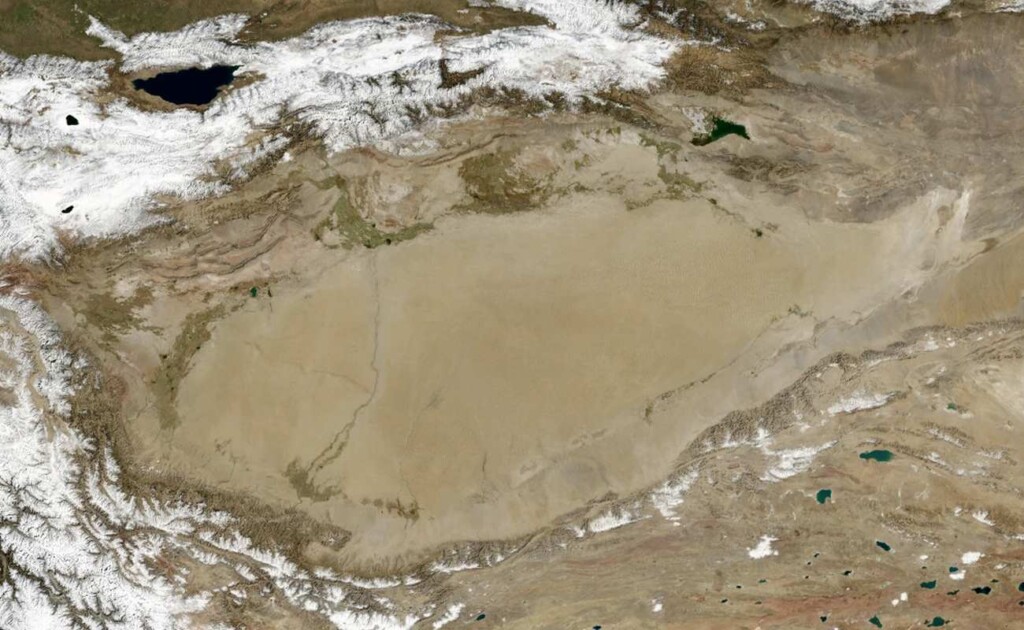

Photographer: Alen Alex

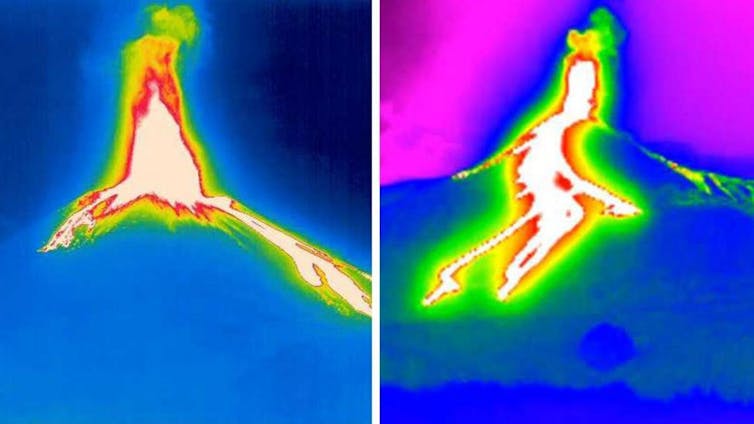

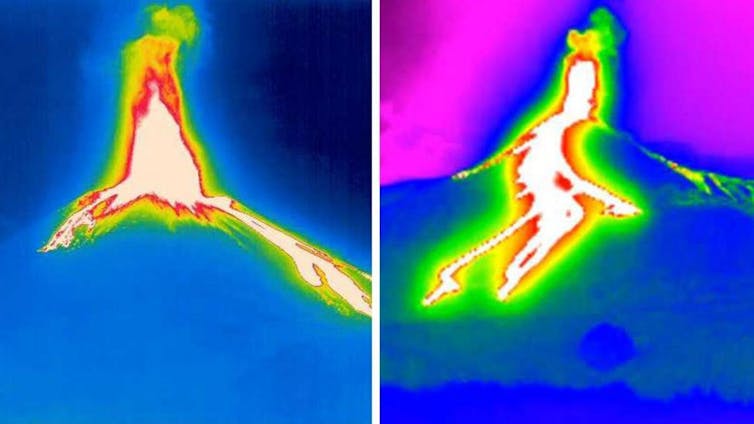

Photographer: Alen Alex  Thermal camera images show the eruption and flows of lava down the side of Mount Etna. National Institute of Geophysics and Volcanology, CC BY

Thermal camera images show the eruption and flows of lava down the side of Mount Etna. National Institute of Geophysics and Volcanology, CC BYOn Monday morning local time, a huge cloud of ash, hot gas and rock fragments began spewing from Italy’s Mount Etna.

An enormous plume was seen stretching several kilometres into the sky from the mountain on the island of Sicily, which is the largest active volcano in Europe.

While the blast created an impressive sight, the eruption resulted in no reported injuries or damage and barely even disrupted flights on or off the island. Mount Etna eruptions are commonly described as “Strombolian eruptions” – though as we will see, that may not apply to this event.

The eruption began with an increase of pressure in the hot gases inside the volcano. This led to the partial collapse of part of one of the craters atop Etna.

The collapse allowed what is called a pyroclastic flow: a fast-moving cloud of ash, hot gas and fragments of rock bursting out from inside the volcano.

Thermal camera images show the eruption and flows of lava down the side of Mount Etna. National Institute of Geophysics and Volcanology, CC BY

Thermal camera images show the eruption and flows of lava down the side of Mount Etna. National Institute of Geophysics and Volcanology, CC BYNext, lava began to flow in three different directions down the mountainside. These flows are now cooling down. On Monday evening, Italy’s National Institute of Geophysics and Volcanology announced the volcanic activity had ended.

Etna is one of the most active volcanoes in the world, so this eruption is reasonably normal.

Volcanologists classify eruptions by how explosive they are. More explosive eruptions tend to be more dangerous, because they move faster and cover a larger area.

At the mildest end are Hawaiian eruptions. You have probably seen pictures of these: lava flowing sedately down the slope of the volcano. The lava damages whatever it runs into, but it’s a relatively local effect.

As eruptions grow more explosive, they send ash and rock fragments flying further afield.

At the more explosive end of the scale are Plinian eruptions. These include the famous eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79AD, described by the Roman writer Pliny the Younger, which buried the Roman towns of Pompeii and Herculaneum under metres of ash.

In a Plinian eruption, hot gas, ash, and rock can explode high enough to reach the stratosphere – and when the eruption column collapses, the debris falls to Earth and can wreak terrifying destruction over a huge area.

What about Strombolian eruptions? These relatively mild eruptions are named after Stromboli, another Italian volcano which belches out a minor eruption every 10 to 20 minutes.

In a Strombolian eruption, chunks of rock and cinders may travel tens or hundreds of metres through the air, but rarely further. The pyroclastic flow from yesterday’s eruption at Etna was rather more explosive than this – so it wasn’t strictly Strombolian.

Volcanic eruptions are a bit like weather. They are very hard to predict in detail, but we are a lot better than we used to be at forecasting them.

To understand what a volcano will do in the future, we first need to know what is happening inside it right now. We can’t look inside directly, but we do have indirect measurements.

For example, before an eruption magma travels from deep inside the Earth up to the surface. On the way, it pushes rocks apart and can generate earthquakes. If we record the vibrations of these quakes, we can track the magma’s journey from the depths.

Rising magma can also make the ground near a volcano bulge upwards very slightly, by a few millimetres or centimetres. We can monitor this bulging, for example with satellites, to gather clues about an upcoming eruption.

Some volcanoes release gas even when they are not strictly erupting. We can measure the chemicals in this gas – and if they change, it can tell us that new magma is on its way to the surface.

When we have this information about what’s happening inside the volcano, we also need to understand its “personality” to know what the information means for future eruptions.

As a volcanologist, I often hear from people that it seems there are more volcanic eruptions now than in the past. This is not the case.

What is happening, I tell them, is that we have better monitoring systems now, and a very active global media system. So we know about more eruptions – and even see photos of them.

Monitoring is extremely important. We are fortunate that many volcanoes in places such as Italy, the United States, Indonesia and New Zealand have excellent monitoring in place.

This monitoring allows local authorities to issue warnings when an eruption is imminent. For a visitor or tourist out to see the spectacular natural wonder of a volcano, listening to these warnings is all-important.![]()

Teresa Ubide, ARC Future Fellow and Associate Professor in Igneous Petrology/Volcanology, The University of Queensland

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

It’s just past midnight in the cool, ancient forests of Tasmania. We’ve spent a long day and night surveying endangered Tasmanian devils. All around, small animals scurry through bushes. A devil calls in the darkness. Microbats swoop and swirl as a spotted-tailed quoll slips through the shadows. Working here is spine-tingling and electric.

Weeks later, we’re in a moonlit forest in Victoria. It was logged a few years earlier and burnt by bushfire a few decades before that. The old trees are gone. So too are the quolls, bats and moths that once dwelled in their hollows. Invasive blackberry chokes what remains. The silence is deafening, and devastating.

In our work as field biologists, we often desperately wish we saw a place before it was cleared, logged, burnt or overtaken by invasive species. Other times, we hold back tears as we read about the latest environmental catastrophe, overwhelmed by anger and frustration. Perhaps you know this feeling of grief?

The new year is a chance to reflect on the past and consider future possibilities. Perhaps we’ll sign up to the gym, spend more time with family, or – perish the thought – finally get to the dentist.

But let us also set a New Year’s resolution for nature. Let’s make a personal pledge to care for beetles and butterflies, rainforests and reefs, for ourselves, and for future generations. Because now, more than ever — when the natural world seems to be on the precipice — it’s not too late to be a catalyst for positive change.

Our work brings us up close to the beauty of nature. We trek through deserts, stumble through forests and trudge over snowy mountains to study and conserve Australia’s unique wildlife.

But we must also confront devastating destruction. The underlying purpose of our work – trying to save species before it is too late – is almost always heartbreaking. It is a race we cannot always win.

Since Europeans arrived in Australia, much of the country has become severely degraded.

Around 40% of our forests and 99% of grasslands have been cut down and cleared, and much of what remains is under threat. Thousands of ecological communities, plants and animal species are threatened with extinction.

And it seems the news only gets worse. The global average temperature for the past decade is the warmest on record, about 1.2°C above the pre-industrial average. Severe bushfires are more and more likely. Yet Australia’s federal government recently approved four coalmine expansions.

Australia remains a global logging and deforestation hotspot. We have the world’s worst record for mammal extinctions and lead the world in arresting climate and environment protesters.

To top it off, a recent study estimated more than 9,000 native Australian animals, mostly invertebrates, have gone extinct since European arrival. That’s between one and three species every week.

Many will never be formally listed, named or known. Is this how the world ends – not with a bang, but with a silent invertebrate apocalypse?

The degradation of our environment affects more than distant plants and animals. It resonates deeply with many humans, too.

Ecological grief is an emotional response to environmental degradation and climate change, damaging our mental health and wellbeing. It can manifest as sadness, anxiety, despair or helplessness. Or it might bring a profound sense of guilt that we all, directly or indirectly, contribute to the problems facing the natural world.

Academic research on ecological grief is growing rapidly, but the concept has been around for decades.

In 1949, American writer and philosopher Aldo Leopold – widely considered the father of wildlife ecology and modern conservation – eloquently wrote in his book A Sand County Almanac that:

One of the penalties of an ecological education is that one lives alone in a world of wounds. Much of the damage inflicted on land is quite invisible to laymen. An ecologist must either harden his shell and make believe that the consequences of science are none of his business, or he must be the doctor who sees the marks of death in a community that believes itself well and does not want to be told otherwise.

Ecological grief is certainly a heavy burden. But it can also be a catalyst for change.

So how do we unlock the transformative potential of ecological grief?

In our experience, it first helps to share our experience with colleagues, friends and family. It’s important to know others have similar feelings and that we are not alone.

Next, remember that it is not too late to act – passivity is the enemy of positive change. It’s vital to value and protect what remains, and restore what we can.

Taking action doesn’t just help nature, it’s also a powerful way to combat feelings of helplessness and grief. It might involve helping local wildlife, supporting environmental causes, reducing meat consumption, or – perhaps most importantly – lobbying political representatives to demand change.

Lastly, for environmental professionals such as us, celebrating wins – no matter how small – can help buoy us to fight another day.

We are encouraged by our proud memories of helping return the mainland eastern barred bandicoot to the wild. The species was declared extinct on mainland Australia in 2013. After more than three decades of conservation action, it was taken off the “extinct in the wild list” in 2021, a first for an Australian threatened species.

Our work to support mountain pygmy-possum populations after the Black Summer fires helped to ease our grief at the loss of so many forests, as did seeing the end of native forest logging in Victoria a year ago.

So, for our New Year’s resolution, let’s harness our ecological grief to bring about positive change. Let’s renew the fight to return those lost voices, and protect our remaining ancient ecosystems. We can, and must, do better – because so much depends on it.

And maybe, just maybe, we’ll finally get to the dentist.![]()

Darcy Watchorn, Threatened Species Biologist, Wildlife Conservation & Science Department, Zoos Victoria, and Visiting Scholar, School of Life & Environmental Science, Deakin University and Marissa Parrott, Senior Conservation Biologist, Wildlife Conservation & Science, Zoos Victoria, and Honorary Research Associate, BioSciences, The University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Queensland is widely known as the land clearing capital of Australia. But what’s not so well known is many of the cleared trees can grow back naturally.

The latest state government figures show regrowth across more than 7.6 million hectares in Queensland in 2020-21. These trees, though young, still provide valuable habitat for many threatened species – as long as they’re not bulldozed again.

Our new research explored the benefits of regrowth for 30 threatened animal species in Queensland. We found regrown forests and woodlands provided valuable habitat and food for species after an average of 15 years. Some species were likely to benefit from trees as young as three years.

This presents an opportunity for governments to support landowners and encourage them to retain more regrowing forest and woodland, especially where it can provide much-needed habitat for wildlife. But it’s a challenge because there is strong pressure to clear regrowth, largely to maintain pasture.

We focused on threatened animal species that depend on forests and woodlands, and occur in regions with substantial regrowth.

We wanted to find out which species use regrowth, and how old the trees need to be. But there’s not much survey data available on threatened species living in naturally regenerated forest and woodlands.

To elicit this information we asked almost 50 experts to complete a detailed questionnaire and attend a workshop.

We found 15 years was the average minimum age at which regrowth became useful to threatened species. But the full range was 3-68 years, depending on factors such as what a species eats, how it moves through the landscape and whether it needs tree hollows for shelter or breeding.

For example, one threatened bird (the squatter pigeon) could use woodlands as young as three years old. Koalas benefited from regrowth as young as nine years old.

Some species, such as the greater glider, need much older forests. This is because they require large tree hollows to shelter in during the day, and large trees to feed on and move between at night.

So young forests shouldn’t be seen as an alternative to protecting old forests. We need both.

We also estimated the proportion of each species’ current habitat that comprises regrowth, using satellite data and publicly available data.

For some species, we found regrowth made up almost a third of their potential habitat in Queensland. On average, it was 18%.

However, nearly three-quarters of the habitat lost in Queensland since 2018 was regrowth forests and woodlands. So while the loss of older, “remnant” vegetation is more damaging per unit area, the regrowth habitat is being lost on a bigger scale.

Our research suggests retaining more regrowth could be an easy and cost-effective way to help save threatened species.

In contrast, tree planting is time-consuming and expensive. What’s more, only 10% of our native plants are readily available as seeds for sale. This, combined with more extreme weather such as prolonged droughts, often causes restoration projects to fail.

The fact that habitat can regrow naturally in parts of Queensland is a huge bonus. But farmers also need to maintain productivity, which can decrease if there’s too much regrowth.

So, how do we help these landowners retain more regrowth?

One way is to provide incentives. For example, government-funded biodiversity stewardship schemes provide payments to cover the costs of managing the vegetation – such as fencing off habitat and managing weeds – as well as compensation for loss of agricultural production. Targeting areas of regrowth with high habitat values could be a way for such schemes to benefit wildlife.

Alternatively, market-based schemes allow landowners to generate biodiversity or carbon “credits” by keeping more trees on their property. Then, businesses (or governments) buy these credits. For example, some big emitters in Australia have to purchase carbon credits to “offset” their own emissions.

However, Australia’s carbon market has been accused of issuing “low integrity” carbon credits. This means the carbon credits were paid for projects that may not have captured and stored the amount of carbon they were supposed to. To make sure these markets work, robust methods are needed – and until now, there hasn’t been one that worked to retain regrowth.

In February, the Queensland government released a method by which landholders could generate carbon credits by agreeing not to clear their regrowing woodlands and forests.

The new carbon method provides a promising opportunity to allow landowners to diversify their farm income.

In addition, tree cover brings direct, on-farm benefits such as more shade and shelter for livestock, natural pest control and better soil health.

At a landscape level, greater tree cover can improve local climate regulation, reduce sediment run-off to the Great Barrier Reef and reduce Australia’s carbon emissions.

Ideally, Australia’s carbon and biodiversity markets would work alongside sufficient government funding for nature recovery, which needs to increase to at least 1% (currently it’s around 0.1%).

Meanwhile, our research has shown embracing natural regeneration potential in Queensland will have benefits for a range of threatened species too.

We acknowledge our research coauthors, Jeremy Simmonds (2rog Consulting), Michelle Ward (Griffith University) and Teresa Eyre (Queensland Department of Environment, Tourism, Science and Innovation).![]()

Hannah Thomas, PhD candidate in Environmental Policy, The University of Queensland and Martine Maron, Professor of Environmental Management, The University of Queensland

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

credit – Marcin Kopij

credit – Marcin Kopij

three to ten centimeters, depending on the time of year, longer leaves with robust traps are usually formed after flowering. Flytraps that have more than 7 leaves are colonies formed by rosettes that have divided beneath the ground. Illustration from Curtis's Botanical Magazine byWilliam Curtis (1746–1799) The leaf blade is divided into two regions: a flat, heart-shaped photosynthesis-capable petiole, and a pair of terminal lobes hinged at the midrib, forming the trap which is the true leaf. The upper surface of these lobes contains red anthocyanin pigments and its edges secrete mucilage. The lobes exhibit rapid plant movements, snapping shut when stimulated by prey. The trapping mechanism is tripped when prey contacts one of the three hair-like trichomes that are found on the upper surface of each of the lobes. The trapping mechanism is so specialized that it can distinguish between living prey and non-prey stimuli such as falling raindrops; two trigger hairs must be touched in succession within 20 seconds of each other or one hair touched twice in rapid succession, whereupon the lobes of the trap will snap shut in about one-tenth of a second. The edges of the lobes are fringed by stiff hair-like protrusions or cilia, which mesh together and prevent large prey from escaping. (These protrusions, and the trigger hairs, also known as sensitive hairs, are probablyhomologous with the tentacles found in this plant’s close relatives, the sundews.) Scientists have concluded that the Venus flytrap is closely related to Drosera (sundews), and that the snap trap evolved

three to ten centimeters, depending on the time of year, longer leaves with robust traps are usually formed after flowering. Flytraps that have more than 7 leaves are colonies formed by rosettes that have divided beneath the ground. Illustration from Curtis's Botanical Magazine byWilliam Curtis (1746–1799) The leaf blade is divided into two regions: a flat, heart-shaped photosynthesis-capable petiole, and a pair of terminal lobes hinged at the midrib, forming the trap which is the true leaf. The upper surface of these lobes contains red anthocyanin pigments and its edges secrete mucilage. The lobes exhibit rapid plant movements, snapping shut when stimulated by prey. The trapping mechanism is tripped when prey contacts one of the three hair-like trichomes that are found on the upper surface of each of the lobes. The trapping mechanism is so specialized that it can distinguish between living prey and non-prey stimuli such as falling raindrops; two trigger hairs must be touched in succession within 20 seconds of each other or one hair touched twice in rapid succession, whereupon the lobes of the trap will snap shut in about one-tenth of a second. The edges of the lobes are fringed by stiff hair-like protrusions or cilia, which mesh together and prevent large prey from escaping. (These protrusions, and the trigger hairs, also known as sensitive hairs, are probablyhomologous with the tentacles found in this plant’s close relatives, the sundews.) Scientists have concluded that the Venus flytrap is closely related to Drosera (sundews), and that the snap trap evolved from a fly-paper trap similar to that of Drosera. The holes in the meshwork allow small prey to escape, presumably because the benefit that would be obtained from them would be less than the cost of digesting them. If the prey is too small and escapes, the trap will reopen within 12 hours. If the prey moves around in the trap, it tightens and digestion begins more quickly. Speed of closing can vary depending on the amount of humidity, light, size of prey, and general growing conditions. The speed with which traps close can be used as an indicator of a plant's general health. Venus flytraps are not as humidity-dependent as are some other carnivorous plants, such as Nepenthes, Cephalotus, most Heliamphora, and some Drosera. The Venus flytrap exhibits variations in petiole shape and length and whether the leaf lies flat on the ground or extends up at an angle of about 40–60 degrees. The four major forms are: 'typica', the most common, with broad decumbent petioles; 'erecta', with leaves at a 45-degree angle; 'linearis', with narrow petioles and leaves at 45 degrees; and 'filiformis', with extremely narrow or linear petioles. Except for 'filiformis', all of these can be stages in leaf production of any plant depending on season (decumbent in summer versus short versus semi-erect in spring), length of photoperiod (long petioles in spring versus short in summer), and intensity of light (wide petioles in low light intensity versus narrow in brighter light). When grown from seed, plants take around four to five years to reach maturity and will live for 20 to 30 years if cultivated in the right conditions. Courtesy: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Venus_flytrap, Open images in browser to find its source of sharing.

from a fly-paper trap similar to that of Drosera. The holes in the meshwork allow small prey to escape, presumably because the benefit that would be obtained from them would be less than the cost of digesting them. If the prey is too small and escapes, the trap will reopen within 12 hours. If the prey moves around in the trap, it tightens and digestion begins more quickly. Speed of closing can vary depending on the amount of humidity, light, size of prey, and general growing conditions. The speed with which traps close can be used as an indicator of a plant's general health. Venus flytraps are not as humidity-dependent as are some other carnivorous plants, such as Nepenthes, Cephalotus, most Heliamphora, and some Drosera. The Venus flytrap exhibits variations in petiole shape and length and whether the leaf lies flat on the ground or extends up at an angle of about 40–60 degrees. The four major forms are: 'typica', the most common, with broad decumbent petioles; 'erecta', with leaves at a 45-degree angle; 'linearis', with narrow petioles and leaves at 45 degrees; and 'filiformis', with extremely narrow or linear petioles. Except for 'filiformis', all of these can be stages in leaf production of any plant depending on season (decumbent in summer versus short versus semi-erect in spring), length of photoperiod (long petioles in spring versus short in summer), and intensity of light (wide petioles in low light intensity versus narrow in brighter light). When grown from seed, plants take around four to five years to reach maturity and will live for 20 to 30 years if cultivated in the right conditions. Courtesy: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Venus_flytrap, Open images in browser to find its source of sharing.