Credit: iStock.

Using artificial intelligence shortens the time to identify complex quantum phases in materials from months to minutes, finds a new study published in Newton. The breakthrough could significantly speed up research into quantum materials, particularly low-dimensional superconductors.

The study was led by theorists at Emory University and experimentalists at Yale University. Senior authors include Fang Liu and Yao Wang, assistant professors in Emory’s Department of Chemistry, and Yu He, assistant professor in Yale’s Department of Applied Physics.

The team applied machine-learning techniques to detect clear spectral signals that indicate phase transitions in quantum materials — systems where electrons are strongly entangled. These materials are notoriously difficult to model with traditional physics because of their unpredictable fluctuations.

“Our method gives a fast and accurate snapshot of a very complex phase transition, at virtually no cost,” says Xu Chen, the study’s first author and an Emory PhD student in chemistry. “We hope this can dramatically speed up discoveries in the field of superconductivity.”

One of the challenges in applying machine learning to quantum materials is the lack of sufficient high-quality experimental data needed to train models. To overcome this, the researchers used high-throughput simulations to generate large amounts of data. They then combined these simulation results with just a small amount of experimental data to create a powerful and efficient machine-learning framework.

“This is like training self-driving cars,” Liu explains. “You might test them extensively in Atlanta, but you want them to perform reliably in New Haven, or really, anywhere. So, the question is: how do we make the learning both transferable and understandable?”

Their framework allows machine learning models to recognize phases in experimental data —even from just a single spectral snapshot — by applying the insights gained from simulations. This approach tackles the ongoing challenge of limited experimental data in scientific machine learning and opens the door to faster, more scalable exploration of quantum materials and molecular systems.

Other contributors to the study include Yuanjie Sun, a former undergraduate at Clemson University; Eugen Hruska, a former postdoctoral researcher at Emory; Vivek Dixit, a former postdoctoral researcher at Clemson; and Jinming Yang, a PhD student at Yale.

Quantum fluctuations: angel and demon

Quantum materials are a special class of materials in which particles like electrons and atoms behave in ways that defy classical physics. One of their most fascinating features is a quantum phenomenon called entanglement, where particles influence each other at a far distance. A popular analogy is Schrödinger’s cat — a thought experiment in which a cat can be both alive and dead at the same time. In quantum materials, electrons can behave similarly, acting collectively rather than individually.

These unusual correlations, or more precisely fluctuations, are what give quantum materials their remarkable properties. One of the best-known examples is high-temperature superconductivity found in copper-oxide compounds, or cuprates, where electricity flows without resistance under certain conditions.

But while fluctuations often accompany these powerful properties, they also make many physical properties incredibly difficult to understand, measure and design. Traditional methods for identifying phase transitions in materials rely on something called the spectral gap – the energy needed to break superconducting electron pairs. However, in systems with strong fluctuations, this method breaks down.

“Instead, it is the level of global coordination between gazillions of superconducting electrons, or the quantum ‘phase,’ that governs the transition,” says He, who recently published a study revealing a surprisingly wide extent of this effect.

“It’s like moving to a different country where everyone speaks a different language — you can’t just rely on what worked before,” Wang adds.

This means scientists can’t easily determine the transition temperature — the point at which superconductivity kicks in — just by looking at the spectral gap. Finding better ways to characterize these transitions is crucial for efficiently discovering new quantum materials and designing them for real-world applications.

High-temperature superconductivity

Superconductivity — the ability of certain materials to conduct electricity with zero energy loss — is one of the most fascinating phenomena in quantum physics. It was discovered in 1911, when scientists found that mercury completely lost its electrical resistance at 4 Kelvin (-452°F), a temperature colder than any natural place in our solar system.

It wasn’t until 1957 that scientists were able to fully explain how superconductivity works. At everyday temperatures, electrons in a material move independently and frequently collide with atoms, losing energy in the process. But at very low temperatures, electrons can team up and form a new state of matter. In this paired state, they move in perfect sync, like a well-choreographed dance, allowing electricity to flow without resistance.

A major breakthrough came in 1986 with the discovery of cuprate superconductors. These materials can superconduct at temperatures as high as 130 Kelvin (-211°F), which, while still cold, is warm enough to be reached using inexpensive liquid nitrogen. This made practical applications of superconductivity much more realistic.

However, cuprates belong to the class of quantum materials, where the behavior of electrons is governed by entanglement and strong quantum fluctuations. These material phases are complex and hard to predict using traditional theories, making them both exciting and challenging to study.

Today, scientists around the world are racing to unlock the full potential of superconductors. The ultimate goal is to create materials that can superconduct at room temperature. If successful, this could revolutionize everything from power grids to computing — allowing electricity to flow with perfect efficiency, without heat or waste.

A new approach

The researchers wanted to use a machine learning model to overcome this obstacle.

Machine learning models, however, need training on vast quantities of labeled data to learn how to effectively distinguish a particular feature from surrounding noise. The catch of course, is the low volume of experimental data on phase transitions in correlated materials.

The researchers took the approach of a domain-adversarial neural network (DANN), an image-recognition training approach similar to that used in the technology behind self-driving cars. Rather than input millions of images of cats into the machine learning model, it’s more practical to identify and extract key features of cats. For instance, simple, simulated, 3D images showing the essential features of a cat can be photographed from many different angles to capture the synthetic data needed to train a model to recognize a real cat.

“In the same way, by simulating data for the essential features of the thermodynamic phase transition we can train a machine learning model to recognize it,” Chen says. “And that opens up a lot of new space that we can explore much more quickly than we can through real-life experiments. As long as we have an understanding of the key characteristics in a system, we can rapidly generate thousands of images to train a machine learning model to identify this pattern.”

These patterns, he adds, are directly applicable to probe the superconducting phase of real experimental spectra.

Their novel, data-driven approach leverages the limited amount of experimental spectroscopy data on correlated materials by combining it with large amounts of simulated data. The key signatures for phase transition used in the model makes the AI decision-making process underlying it transparent and explainable.

Validating the model

The Yale team of physicists tested the machine learning model through experiments with a cuprate. The results showed that the method can distinguish between superconducting and non-superconducting phases with nearly 98% accuracy.

And unlike traditional machine-learning, assisted-feature extraction in spectroscopy, the new method pinpoints phase transitions based on characteristic spectral features inside an energy gap, making it more robust and generalizable to a range of materials. That boosts the model’s potential for high-throughput analyses.

By demonstrating the power of machine learning to overcome experimental limitations for data, the work overcomes a long-standing challenge in quantum materials research, clearing the path for faster discoveries that could impact everything from energy-efficient electronics to next-generation computing.

Reference: Chen X, Sun Y, Hruska E, et al. Detecting thermodynamic phase transition via explainable machine learning of photoemission spectroscopy. Newton. 2025:100066. doi:

10.1016/j.newton.2025.100066

Iron-air batteries for stable power – Credit: Form Energy

Iron-air batteries for stable power – Credit: Form Energy

Photo by Hamish on Unsplash

Photo by Hamish on Unsplash Worms collected in the Chornobyl Exclusion Zone – SWNS / New York University

Worms collected in the Chornobyl Exclusion Zone – SWNS / New York University

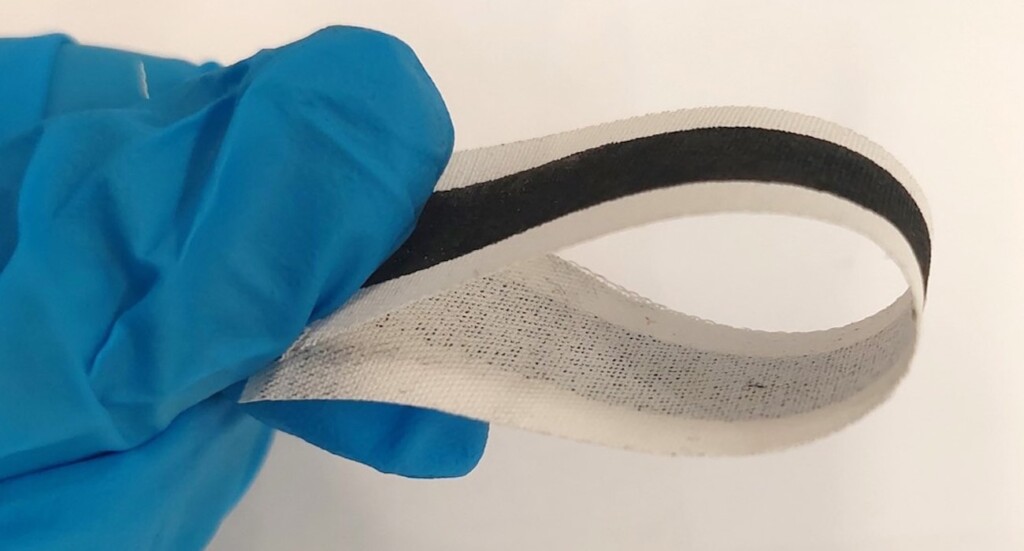

Flexible inkjet printed E-textile – Credit: Marzia Dulal

Flexible inkjet printed E-textile – Credit: Marzia Dulal Gloves with e-textile sensors monitoring heart rate – Credit: Marzia Dulal

Gloves with e-textile sensors monitoring heart rate – Credit: Marzia Dulal Four strips in a variety of decomposed states, during four months of decomposition – Credit: Marzia Dulal

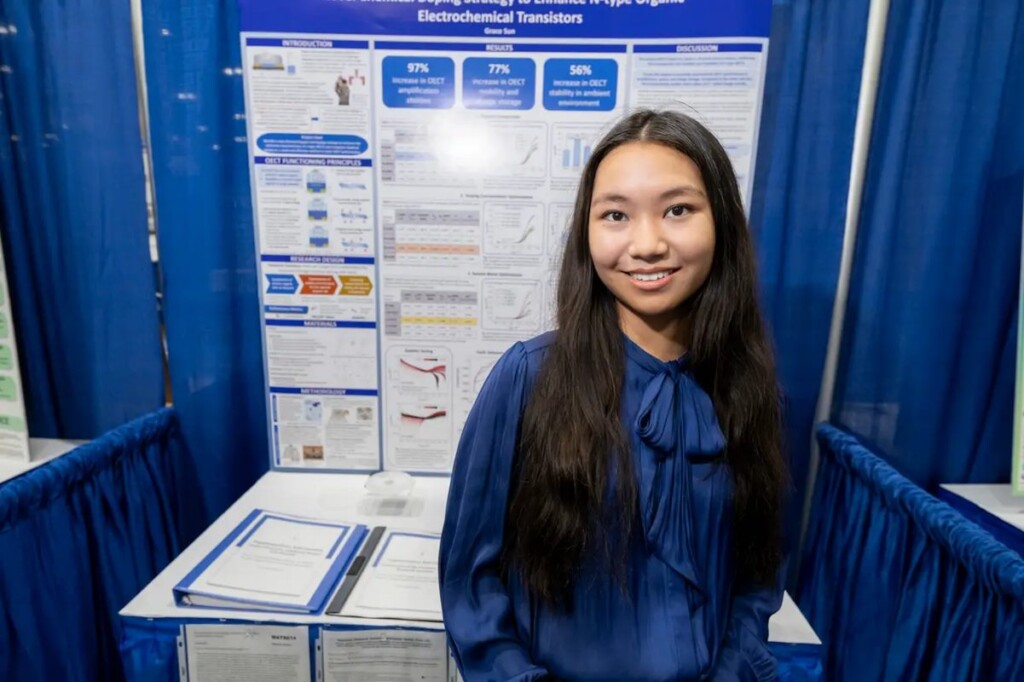

Four strips in a variety of decomposed states, during four months of decomposition – Credit: Marzia Dulal Grace Sun, credit – Society for Science

Grace Sun, credit – Society for Science

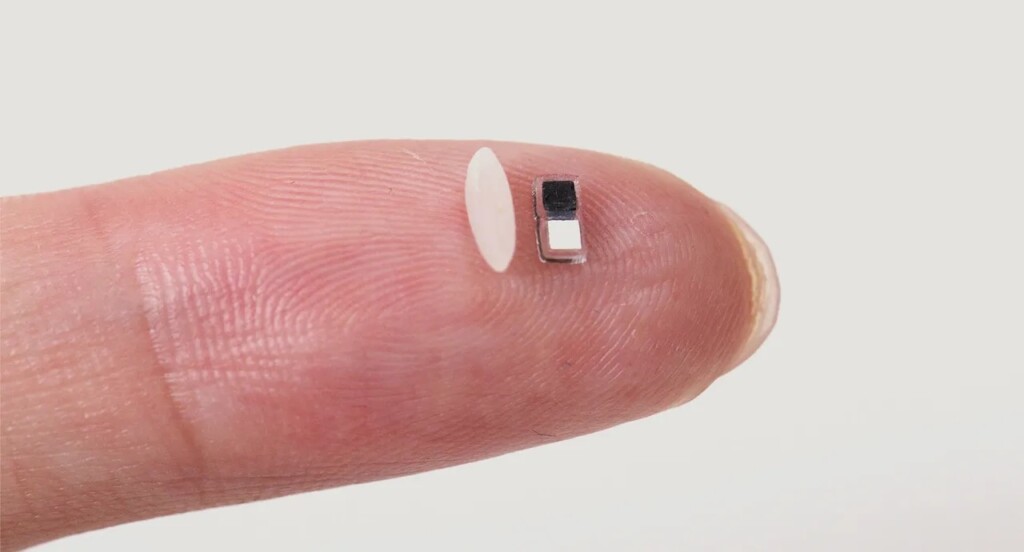

World’s smallest pacemaker next to a grain of rice – Credit: John Rogers / Northwestern University press release

World’s smallest pacemaker next to a grain of rice – Credit: John Rogers / Northwestern University press release

Ngururrpa Ranger Lucinda Gibson gently holding the unfertilised night parrot egg – credit: supplied by Ngururrpa Rangers.

Ngururrpa Ranger Lucinda Gibson gently holding the unfertilised night parrot egg – credit: supplied by Ngururrpa Rangers. Adult night parrots are ground-dwelling birds that fly – Photo by Steve Murphy

Adult night parrots are ground-dwelling birds that fly – Photo by Steve Murphy