IIT Bombay’s new smart platform to help researchers decode brain diseases

Mom and Baby Beat 1-in-a-Million Odds to Survive the ‘Rarest of Pregnancies’

How facial recognition for bears can help ecologists manage wildlife

Emily Wanderer, University of Pittsburgh

When a grizzly bear attacked a group of fourth- and fifth-graders in western Canada in late November 2025, it sparked more than a rescue effort for the 11 people injured – four with severe injuries. Local authorities began trying to find the specific bear that was involved in order to relocate or euthanize it, depending on the results of their assessment.

The attack, in Bella Coola, British Columbia, was very unusual bear behavior and sparked an effort to figure out exactly what had happened and why. That meant finding the bear involved – which, based on witness statements, was a mother grizzly with two cubs.

Searchers combed the area on foot and by helicopter and trapped four bears. DNA comparisons to evidence from the attack cleared each of the trapped bears, and they were released back to the wild. After more than three weeks without finding the bear responsible for the attack, officials called off the search.

The case highlights the difficulty of identifying individual bears, which becomes important when one is exhibiting unusual behavior. Bears tend to look a lot alike to people, and untrained observers can have a very hard time telling them apart. DNA testing is excellent for telling individuals apart, but it is expensive and requires physical samples from bears. Being trapped and having other contact with humans is also stressful for them, and wildlife managers often seek to minimize trapping.

Recent advances in computer vision and other types of artificial intelligence offer a possible alternative: facial recognition for bears.

As a cultural anthropologist, I study how scientists produce knowledge and technologies, and how new technology is transforming ecological science and conservation practices. Some of my research has looked at the work of computer scientists and ecologists making facial recognition for animals. These tools, which reflect both technological advances and broader popular interest in wildlife, can reshape how scientists and the general public understand animals by getting to know formerly anonymous creatures as individuals.

New ways to identify animals

A facial recognition tool for bears called BearID is under development by computer scientists Ed Miller and Mary Nguyen, working with Melanie Clapham, a behavioral ecologist working for the Nanwakolas Council of First Nations, conducting applied research on grizzly bears in British Columbia.

It uses deep learning, a subset of machine learning that makes use of artificial neural networks, to analyze images of bears and identify individual animals. The photos are drawn from a collection of images taken by naturalists at Knight Inlet, British Columbia, and by National Park Service staff and independent photographers at Brooks River in Katmai National Park, Alaska.

Bears’ bodies change dramatically from post-hibernation skinny in the spring to fat and ready for winter in the fall. However, the geometry of each bear’s face – the arrangement of key features like their eyes and nose – remains relatively stable over seasons and years.

BearID uses an algorithm to locate bear faces in pictures and make measurements between those key features. Each animal has a unique set of measurements, so a photograph of one taken yesterday can be matched with an image taken some time ago.

Miller has built a web tool to automatically detect bears in the webcams from Brooks River that originally inspired the project. The BearID team has also been working with Rebecca Zug, a professor and director of the carnivore lab at the Universidad San Francisco de Quito, to develop a bear identification model for Andean bears to use in bear ecology and conservation research in Ecuador.

Animal faces are less controversial

Human facial recognition is extremely controversial. In 2021, Meta ended the use of its face recognition system, which automatically identified people in photographs and videos uploaded to Facebook. The company described it as a powerful technology that, while potentially beneficial, was currently not suitable for widespread use on its platform.

In the years following that announcement, Meta gradually reintroduced facial recognition technology, using it to detect scams involving public figures and to verify users’ identities after their accounts had been breached.

When used on humans, critics have called facial recognition technology the “plutonium of AI” and a dangerous tool with few legitimate uses. Even as facial recognition has become more widespread, researchers remain convinced of its dangers. Researchers at the American Civil Liberties Union highlight the continued threat to Americans’ constitutional rights posed by facial recognition and the harms caused by inaccurate identifications.

For wildlife, the ethical controversies are perhaps less pressing, although there is still potential for animals to be harmed by people who are using AI systems. And facial recognition could help wildlife managers identify and euthanize or relocate bears that are causing significant problems for people.

Wildlife ecologists sometimes find focusing on individual animals problematic. Naming animals may make them “seem less wild.” Names that carry cultural meaning can also frame people’s interpretations of animal behavior. As the Katmai rangers note, humans may interpret the behaviors of a bear named Killer differently than one named Fluffy.

Wildlife management decisions are meant to be made about groups of animals and areas of territory. When people become connected to individual animals, including by naming them, decisions become more complicated, whether in the wild or in captivity.

When people connect with particular animals, they may object to management decisions that harm individuals for the sake of the health of the population as a whole. For example, wildlife managers may need to move or euthanize animals for the health of the broader population or ecosystem.

But knowing and understanding bears as individual animals can also deepen the fascination and connections people already have with bears.

For example, Fat Bear Week, an annual competition hosted by explore.org and Katmai National Park, drew over a million votes in 2025 as people campaigned and voted for their favorite bear. The winner was Bear 32, also known as “Chunk.” Chunk was identified in photographs and videos the old-fashioned way, based on human observations of distinguishing characteristics – such as a large scar across his muzzle and a broken jaw.

In addition to identifying problematic animals, I believe algorithmic tools like facial recognition could help an even broader audience of humans deepen their understanding of bears as a whole by connecting with one or two specific animals.![]()

Emily Wanderer, Associate Professor of Anthropology, University of Pittsburgh

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

First projects selected for INL reactor experiments

_15595.jpg) (Image: INL)

(Image: INL)Samsung's 600-Mile-Range Batteries That Charge in 9 Minutes Ready for Production/Sale Next Year

New Underwater Tool Lets Ecologists ID Fish From Their Sounds–46 Species So Far (LISTEN to 5 of Them)

First Human Cornea Transplant Using 3D Printed, Lab-Grown Tissue Restores Sight in a ‘Game Changer’ for Millions Who are Blind

The first successful human implant of a 3D-printed cornea made from human eye cells cultured in a laboratory has restored a patient’s sight.

The North Carolina-based company that developed the cornea described the procedure as a ‘world first’—and a major milestone toward its goal of alleviating the lack of available donor tissue and long wait-times for people seeking transplants.

According to Precise Bio, its robotic bio-fabrication approach could potentially turn a single donated cornea into hundreds of lab-grown grafts, at a time when there’s currently only one available for an estimated 70 patients who need one to see.

“This achievement marks a turning point for regenerative ophthalmology—a moment of real hope for millions living with corneal blindness,” Aryeh Batt, Precise Bio’s co-founder and CEO, said in a statement.

“For the first time, a corneal implant manufactured entirely in the lab from cultured human corneal cells, rather than direct donor tissue, has been successfully implanted in a patient.”

The company said the transplant was performed Oct. 29 in one eye of a patient who was considered legally blind.

“This is a game changer. We’ve witnessed a cornea created in the lab, from living human cells, bring sight back to a human being,” said Dr. Michael Mimouni, director of the cornea unit at Rambam Medical Center in Israel, who performed the procedure.

“It was an unforgettable moment—a glimpse into a future where no one will have to live in darkness because of a shortage of donor tissue.”

Dubbed PB-001, the implant is designed to match the optical clarity, transparency and bio-mechanical properties of a native cornea. Previously tested in animal models, the company said its graft is capable of integrating with a patient’s own tissue.

The outer layer of the eye—covering the iris and pupil—can end up clouding a person’s vision following injuries, infections, scarring and other conditions. PB-001 is currently being tested in a single-arm phase 1 trial in Israel, which aims to enroll between 10 and 15 participants with excess fluid buildups in the cornea due to dysfunction within its inner cell layers.

Precise Bio said it plans to announce top-line results from the study in the second half of 2026, tracking six-month efficacy outcomes.

The corneas are designed to be compatible with current surgery hardware and workflows. Shipped under long-term cryopreservation, it is delivered preloaded on standard delivery devices and unrolls during implantation to form a natural corneal shape.

“PB-001 has the potential to offer a new, standardized solution to one of ophthalmology’s most urgent needs—reliable, safe, and effective corneal replacement,” said Anthony Atala, M.D., co-founder of Precise Bio and director of the Wake Forest Institute for Regenerative Medicine.

“The ability to produce patient-ready tissue on demand could lead the way towards reshaping transplant medicine as we know it.”(Edited from original article by Conor Hale) First Human Cornea Transplant Using 3D Printed, Lab-Grown Tissue Restores Sight in a ‘Game Changer’ for Millions Who are Blind

Volcanic ash plume from Ethiopia moving over North India will not impact AQI: Experts

TinyML: The Small Technology Tackling the Biggest Climate Challenge

Indian startups file 83,000 patents in FY23; AI, neurotechnology lead

IANS Photo

IANS PhotoWhat are climate tipping points? They sound scary, especially for ice sheets and oceans, but there’s still room for optimism

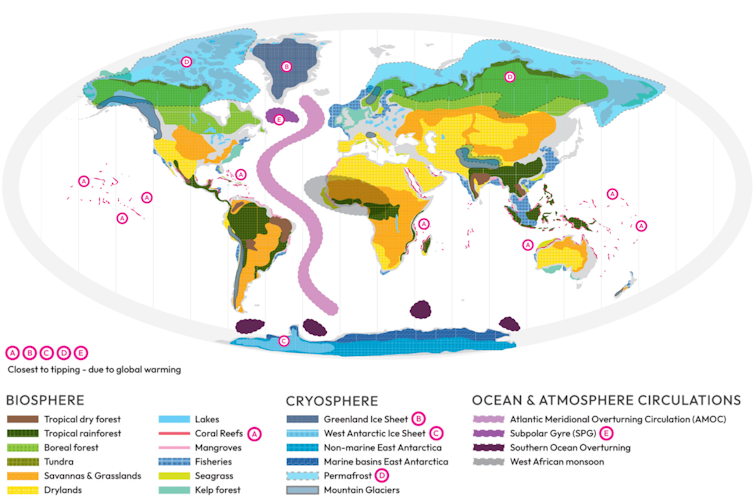

Pink circles show the systems closest to tipping points. Some would have regional effects, such as loss of coral reefs. Others are global, such as the beginning of the collapse of the Greenland ice sheet. Global Tipping Points Report, CC BY-ND

Pink circles show the systems closest to tipping points. Some would have regional effects, such as loss of coral reefs. Others are global, such as the beginning of the collapse of the Greenland ice sheet. Global Tipping Points Report, CC BY-NDScientists have long warned that if global temperatures warmed more than 1.5 degrees Celsius (2.7 Fahrenheit) compared with before the Industrial Revolution, and stayed high, they would increase the risk of passing multiple tipping points. For each of these elements, like the Amazon rain forest or the Greenland ice sheet, hotter temperatures lead to melting ice or drier forests that leave the system more vulnerable to further changes.

Worse, these systems can interact. Freshwater melting from the Greenland ice sheet can weaken ocean currents in the North Atlantic, disrupting air and ocean temperature patterns and marine food chains.

Pink circles show the systems closest to tipping points. Some would have regional effects, such as loss of coral reefs. Others are global, such as the beginning of the collapse of the Greenland ice sheet. Global Tipping Points Report, CC BY-ND

Pink circles show the systems closest to tipping points. Some would have regional effects, such as loss of coral reefs. Others are global, such as the beginning of the collapse of the Greenland ice sheet. Global Tipping Points Report, CC BY-NDWith these warnings in mind, 194 countries a decade ago set 1.5 C as a goal they would try not to cross. Yet in 2024, the planet temporarily breached that threshold.

The term “tipping point” is often used to illustrate these problems, but apocalyptic messages can leave people feeling helpless, wondering if it’s pointless to slam the brakes. As a geoscientist who has studied the ocean and climate for over a decade and recently spent a year on Capitol Hill working on bipartisan climate policy, I still see room for optimism.

It helps to understand what a tipping point is – and what’s known about when each might be reached.

Tipping points are not precise

A tipping point is a metaphor for runaway change. Small changes can push a system out of balance. Once past a threshold, the changes reinforce themselves, amplifying until the system transforms into something new.

Almost as soon as “tipping points” entered the climate science lexicon — following Malcolm Gladwell’s 2000 book, “The Tipping Point: How Little Things Can Make a Big Difference” — scientists warned the public not to confuse global warming policy benchmarks with precise thresholds.

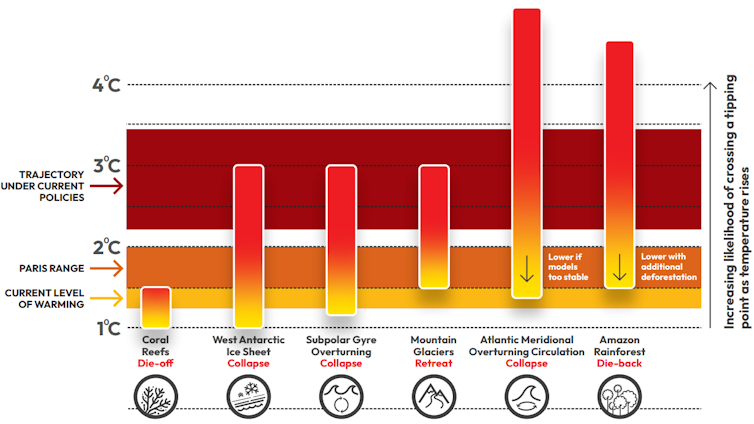

The scientific reality of tipping points is more complicated than crossing a temperature line. Instead, different elements in the climate system have risks of tipping that increase with each fraction of a degree of warming.

For example, the beginning of a slow collapse of the Greenland ice sheet, which could raise global sea level by about 24 feet (7.4 meters), is one of the most likely tipping elements in a world more than 1.5 C warmer than preindustrial times. Some models place the critical threshold at 1.6 C (2.9 F). More recent simulations estimate runaway conditions at 2.7 C (4.9 F) of warming. Both simulations consider when summer melt will outpace winter snow, but predicting the future is not an exact science.

Gradients show science-based estimates from the Global Tipping Points Report of when some key global or regional climate tipping points are increasingly likely to be reached. Every fraction of a degree increases the likeliness, reflected in the warming color. Global Tipping Points Report 2025, CC BY-ND

Gradients show science-based estimates from the Global Tipping Points Report of when some key global or regional climate tipping points are increasingly likely to be reached. Every fraction of a degree increases the likeliness, reflected in the warming color. Global Tipping Points Report 2025, CC BY-NDForecasts like these are generated using powerful climate models that simulate how air, oceans, land and ice interact. These virtual laboratories allow scientists to run experiments, increasing the temperature bit by bit to see when each element might tip.

Climate scientist Timothy Lenton first identified climate tipping points in 2008. In 2022, he and his team revisited temperature collapse ranges, integrating over a decade of additional data and more sophisticated computer models.

Their nine core tipping elements include large-scale components of Earth’s climate, such as ice sheets, rain forests and ocean currents. They also simulated thresholds for smaller tipping elements that pack a large punch, including die-offs of coral reefs and widespread thawing of permafrost.

The world may have already passed one tipping point, according to the 2025 Global Tipping Points Report: Corals reefs are dying as marine temperatures rise. Healthy reefs are essential fish nurseries and habitat and also help protect coastlines from storm erosion. Once they die, their structures begin to disintegrate. Vardhan Patankar/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA

The world may have already passed one tipping point, according to the 2025 Global Tipping Points Report: Corals reefs are dying as marine temperatures rise. Healthy reefs are essential fish nurseries and habitat and also help protect coastlines from storm erosion. Once they die, their structures begin to disintegrate. Vardhan Patankar/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA

Some tipping elements, such as the East Antarctic ice sheet, aren’t in immediate danger. The ice sheet’s stability is due to its massive size – nearly six times that of the Greenland ice sheet – making it much harder to push out of equilibrium. Model results vary, but they generally place its tipping threshold between 5 C (9 F) and 10 C (18 F) of warming.

Other elements, however, are closer to the edge.

Alarm bells sounding in forests and oceans

In the Amazon, self-perpetuating feedback loops threaten the stability of the Earth’s largest rain forest, an ecosystem that influences global climate. As temperatures rise, drought and wildfire activity increase, killing trees and releasing more carbon into the atmosphere, which in turn makes the forest hotter and drier still.

By 2050, scientists warn, nearly half of the Amazon rain forest could face multiple stressors. That pressure may trigger a tipping point with mass tree die-offs. The once-damp rain forest canopy could shift to a dry savanna for at least several centuries.

Rising temperatures also threaten biodiversity underwater.

The second Global Tipping Points Report, released Oct. 12, 2025, by a team of 160 scientists including Lenton, suggests tropical reefs may have passed a tipping point that will wipe out all but isolated patches.

Corals rely on algae called zooxanthellae to thrive. Under heat stress, the algae leave their coral homes, draining reefs of nutrition and color. These mass bleaching events can kill corals, stripping the ecosystem of vital biodiversity that millions of people rely on for food and tourism.

Low-latitude reefs have the highest risk of tipping, with the upper threshold at just 1.5 C, the report found. Above this amount of warming, there is a 99% chance that these coral reefs tip past their breaking point.

Similar alarms are ringing for ocean currents, where freshwater ice melt is slowing down a major marine highway that circulates heat, known as the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation, or AMOC.

A weaker current could create a feedback loop, slowing the circulation further and leading to a shutdown within a century once it begins, according to one estimate. Like a domino, the climate changes that would accompany an AMOC collapse could worsen drought in the Amazon and accelerate ice loss in the Antarctic.

Questions about closeness of other tipping points

Not all scientists agree that an AMOC or rain forest collapse is close.

In the Amazon, researchers recognize the forest’s changes, but some have questioned whether some of the modeled vegetation data that underpins tipping point concerns is accurate. In the North Atlantic, there are similar concerns about data showing a long-term trend.

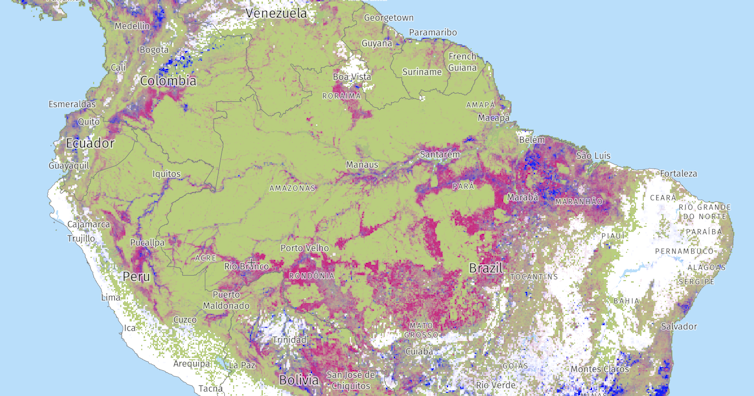

The Amazon forest has been losing tree cover to logging, farming, ranching, wildfires and a changing climate. Pink shows areas with greater than 75% tree canopy loss from 2001 to 2024. Blue is tree cover gain from 2000 to 2020. Global Forest Watch, CC BY

The Amazon forest has been losing tree cover to logging, farming, ranching, wildfires and a changing climate. Pink shows areas with greater than 75% tree canopy loss from 2001 to 2024. Blue is tree cover gain from 2000 to 2020. Global Forest Watch, CC BYOther changes driven by rising global temperatures, like melting permafrost, could be reversed. Permafrost, for example, could refreeze if temperatures drop again.

Risks are too high to ignore

Despite the uncertainty, tipping points are too risky to ignore. Rising temperatures put people and economies around the world at greater risk of dangerous conditions.

But there is still room for preventive actions – every fraction of a degree in warming that humans prevent reduces the risk of runaway climate conditions. Reducing greenhouse gas emissions slows warming and tipping point risks.

Tipping points highlight the stakes, but they also underscore the climate choices humanity can still make to stop the damage.

This article was updated to clarify permafrost discussion.![]()

Alexandra A Phillips, Assistant Teaching Professor in Environmental Communication, University of California, Santa Barbara

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Miracle Recovery for World’s Rarest and Strangest Deer – Just 39 Became 8,200

Pere David’s deer at the Jiangsu Dafeng Elk National Nature Reserve – credit, Jiangsu Dafeng Elk National Nature Reserve

Pere David’s deer at the Jiangsu Dafeng Elk National Nature Reserve – credit, Jiangsu Dafeng Elk National Nature ReserveQualcomm drives digital future with AI, 6G and 'Make in India' initiatives

IANS Photo

IANS PhotoStudy shows eye scans may provide clues to ageing, heart disease risk

(Photo: AI generated image/IANS)

(Photo: AI generated image/IANS)First Antidote for Carbon Monoxide Poisoning 'Cleans' Blood in Minutes

Birds all over the world use the same sound to warn of threats

Superb fairy-wrens attacking a taxidermied shining bronze-cuckoo. William Feeney, CC BY

Superb fairy-wrens attacking a taxidermied shining bronze-cuckoo. William Feeney, CC BYLanguage enables us to connect with each other and coordinate to achieve incredible feats. Our ability to communicate abstract concepts is often seen as a defining feature of our species, and one that separates us from the rest of life on Earth.

This is because while the ability to pair an arbitrary sound with a specific meaning is widespread in human language, it is rarely seen in other animal communication systems. Several recent studies have shown that birds, chimpanzees, dolphins, and elephants also do it. But how such a capacity emerges remains a mystery.

While language is characterised by the widespread use of sounds that have a learned association with the item they refer to, humans and animals also produce instinctive sounds. For example, a scream made in response to pain. Over 150 years ago, naturalist Charles Darwin suggested the use of these instinctive sounds in a new context could be an important step in the development of language-like communication.

In our new study, published today in Nature Ecology and Evolution, we describe the first example of an animal vocalisation that contains both instinctive and learned features – similar to the stepping stone Darwin envisioned.

A unique call towards a unique threat

Birds have a variety of enemies, but brood parasites are unique.

Brood parasites, such as cuckoos, are birds that reproduce by laying their egg in the nest of another species and manipulating the unsuspecting host to incubate their egg and raise their offspring. The first thing a baby cuckoo does after it hatches is heave the other baby birds out of the nest, claiming the effort of its unsuspecting foster parents all to itself.

The high cost of brood parasitism makes it an excellent study system to explore how evolution works in the wild.

For example, our past work has shown that in Australia, the superb fairy-wren has evolved a unique call it makes when it sees a cuckoo. When other fairy-wrens hear this alarm call, they quickly come in and attack the cuckoo.

During these earlier experiments, we couldn’t help but notice other species were responding to this call and making a very similar call themselves. What’s more, discussions with collaborators who were working in countries as far away as China, India and Sweden suggested the birds there were also making a very similar call – and also only towards cuckoos.

Birds from around the world use the same call

First, we explored online wildlife media databases to see if there were other examples of this call towards brood parasites. We found 21 species that produce this call towards their brood parasites, including cuckoos and parasitic finches. Some of these birds were closely related and lived nearby each other, but others shared a last common ancestor over 50 million years ago and live on different continents.

For example, this is a superb fairy-wren responding to a shining bronze-cuckoo in Australia.

And this is a tawny-flanked prinia responding to a cuckoo finch in Zambia.

As vocalisations exist to communicate information, we suspected this call either functioned to attract the attention of their own or other species.

To compare these possibilities, we used a known database of the world’s brood parasites and hosts. If this call exists to communicate information within a species, we expected the species that produce it should be more cooperative, because more birds are better at defending their nest.

We did not find this. Instead, we found that species that produce this call exist in areas with more brood parasites and hosts, suggesting it exists to enable cooperation across different species that are targeted by brood parasites.

Communicating across species to defend against a common threat

To test whether these calls were produced uniquely towards cuckoos in multiple species, we conducted experiments in Australia.

When we presented superb fairy-wrens or white-browed scrubwrens with a taxidermied cuckoo, they made this call and tried to attack it. By contrast, when they were presented with other taxidermied models, such as a predator, this call was very rarely produced.

When we presented the fairy-wrens and scrubwrens with recordings of the call, they responded strongly. This suggests both species produce the call almost exclusively towards cuckoos, and when they hear it they respond predictably.

If this call is something like a “universal word” for a brood parasite across birds, we should expect different species to respond equally to hearing it – even when it is produced by a species they have never seen before. We found exactly this: when we played calls from Australia to birds in China (and vice-versa) they responded the same.

This suggests different species from all around the world use this call because it provides specific information about the presence of a brood parasite.

Superb fairy-wrens attacking a taxidermied shining bronze-cuckoo. William Feeney, CC BY

Superb fairy-wrens attacking a taxidermied shining bronze-cuckoo. William Feeney, CC BYInsights into the origins of language

Our study suggests that over 20 species of birds from all around the world that are separated by over 50 million years of evolution use the same call when they see their respective brood parasite species.

This is fascinating in and of itself. But while these birds know how to respond to the call, our past work has shown that birds that have never seen a cuckoo do not produce this call, but they do after watching others produce it when there is a cuckoo nearby.

In other words, while the response to the call is instinctive, producing the call itself is learned.

Whereas vocalisations are normally either instinctive or learned, this is the first example of an animal vocalisation across species that has both instinctive and learned components. This is important, because it appears to represent a midpoint between the types of vocalisations that are common in animal communication systems and human language.

So, Darwin may have been right about language all along.![]()

William Feeney, Research fellow, Environmental Futures Research Institute, Griffith University; Estación Biológica de Doñana (EBD-CSIC); James Kennerley, Postdoctoral Fellow, Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Cornell University, and Niki Teunissen, Postdoctoral research fellow, Monash University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.