Australia leads first human trial of one-time gene editing therapy to halve bad cholesterol

Parkinson's disease causes progressive changes in brain's blood vessels: Study

Nanotechnology breakthrough may boost treatment for aggressive breast cancer: Study

Climate change is a crisis of intergenerational justice. It’s not too late to make it right

Philippa Collin, Western Sydney University; Judith Bessant, RMIT University, and Rob Watts, RMIT University

Climate change is the biggest issue of our time. 2024 marked both the hottest year on record and the highest levels of carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions in the past two million years.

Global warming increases the frequency and severity of extreme weather events, bushfires, floods and droughts. These are already affecting young people, who will experience the challenges for more of their lives than older people.

It will also adversely affect those not yet born, creating a crisis of intergenerational justice.

Caught in the changing climate

In 2025, children and young people comprise a third of Australia’s population.

Given their early stage of physiological and cognitive development, children are more vulnerable to climate disasters such as crop failures, river floods and drought.

They are also less able to protect themselves from the associated trauma than most older people.

Under current emissions trajectories, United Nations research warns every child in Australia could be subject to more than four heatwaves a year. It’s estimated more than two million Australian children could be living in areas where heatwaves will last longer than four days.

A recent report found more than one million children and young people in Australia experience a climate disaster or extreme weather event in an “average year”.

Those in remote areas, from lower socioeconomic backgrounds and Indigenous children are more likely to be negatively effected. That’s equivalent to one in six children, and numbers are rising.

Anxiety, frustration and fear

The impact of climate change on young people’s health and wellbeing is also significant. Globally, young people bear the greatest psychological burden associated with the impacts of climate change.

Feelings such as frustration, fear and anxiety related to climate change are compounded by the experience of extreme weather events and associated health impacts.

Intergenerational inequality is the term on the lips of policymakers in Canberra and beyond. In this four-part series, we’ve asked leading experts what’s making younger generations worse off and how policy could help fix it.

For young people who live through climate-related disasters, they may experience challenges with education, displacement, housing insecurity and financial difficulties.

All these come on top of other issues. These include increased socioeconomic inequality, rising child poverty, mounting education debt, precarious employment, and lack of access to affordable housing.

This means this generation of young people is likely to be worse off economically than their parents.

Not walking the walk

Some key policy figures understand how climate change is turbo-charging intergenerational unfairness.

Former treasury secretary Ken Henry described the situation as an “intergenerational tragedy”, referring to the ways Australian policymakers are failing to address the changing climate, among other crucial issues.

Even Treasurer Jim Chalmers acknowledged “intergenerational fairness is one of the defining principles of our country”.

Yet, the current responses to the Climate Risk Assessment Report suggest it’s not the highest priority.

Climate change was barely mentioned in the May 2025 federal election. The major parties largely avoided the subject.

It was also concerning that the first major decision of the newly reelected Albanese government was approving an extension to Woodside’s North West Shelf gas project off Western Australia until 2070.

This leaves a legacy to young people of an additional 87 million tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent every year for many years to come.

Raising young voices

Australia’s children and young people are not stupid. Many worked out early that they could not trust governments.

Since 2018, young people have mobilised hundreds of thousands of other children in protests calling for climate action.

Youth-led organisations in Australia, such as the Australian Youth Climate Coalition, have long led campaigns and strategies to address climate change. They are joined by an increasing range of older allies, from Parents for Climate to the Knitting Nannas to the Country Women’s Association.

Domestically, many young people have turned to strategic climate litigation and collaboration with members of parliament on legislative change. They argue governments have a legal duty of care to prevent the harms of climate change.

Thwarted attempts

Beyond accelerating implementation of the National Adaptation Plan, other legislative innovations will help.

In 2023, young people worked with independent Senator David Pocock to draft legislation addressing these concerns.

This bill required governments to consider the health and wellbeing of children and future generations when deciding on projects that could exacerbate climate change.

It was sent to the Senate Environment and Communications Legislation Committee. While all but one of 403 public submissions to the committee supported the bill, in June 2024 the Labor and Coalition members agreed to reject it. They argued it was difficult to quantify notions such as “wellbeing” or “material risk”.

Adding insult to injury, both major parties claimed Australia already had more than adequate environmental laws in place to protect children.

Turning around the Titanic

The Australian parliament may have another opportunity to embed a legislative duty to protect children and secure intergenerational justice. Independent MP Sophie Scamps introduced the Wellbeing of Future Generations Bill in February 2025. As legislation brought before the parliament lapses once an election is called, Scamps is planning to reintroduce the bill in this sitting term.

The bill would introduce a legislative framework to embed the wellbeing of future generations into decision making processes. It would also establish a positive duty and create an independent commissioner for future generations to advocate for Australia’s long-term interests and sustainable practice.

While this bill does not include penalties for breaches of the duty, if passed, it would force the government of the day to consider the rights and interests of current and future generations.

It’s based on similar legislation in Wales, which has worked successfully for a decade.

If nothing else, the Welsh experiment suggests we can take entirely practical steps to promote intergenerational justice, reduce the negative impacts of climate change on young people right now and avert a climate catastrophe threatening our children who are yet to be born.

It may feel like turning around the Titanic, but it must be done.![]()

Philippa Collin, Professor of Political Sociology, Institute for Culture and Society, Western Sydney University; Judith Bessant, Distinguished Professor in School of Global, Urban and Social Studies, RMIT University, and Rob Watts, Professor of Social Policy, RMIT University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Blue, green, brown, or something in between – the science of eye colour explained

You’re introduced to someone and your attention catches on their eyes. They might be a rich, earthy brown, a pale blue, or the rare green that shifts with every flicker of light. Eyes have a way of holding us, of sparking recognition or curiosity before a single word is spoken. They are often the first thing we notice about someone, and sometimes the feature we remember most.

Across the world, human eyes span a wide palette. Brown is by far the most common shade, especially in Africa and Asia, while blue is most often seen in northern and eastern Europe. Green is the rarest of all, found in only about 2% of the global population. Hazel eyes add even more diversity, often appearing to shift between green and brown depending on the light.

So, what lies behind these differences?

It’s all in the melanin

The answer rests in the iris, the coloured ring of tissue that surrounds the pupil. Here, a pigment called melanin does most of the work.

Brown eyes contain a high concentration of melanin, which absorbs light and creates their darker appearance. Blue eyes contain very little melanin. Their colour doesn’t come from pigment at all but from the scattering of light within the iris, a physical effect known as the Tyndall effect, a bit like the effect that makes the sky look blue.

In blue eyes, the shorter wavelengths of light (such as blue) are scattered more effectively than longer wavelengths like red or yellow. Due to the low concentration of melanin, less light is absorbed, allowing the scattered blue light to dominate what we perceive. This blue hue results not from pigment but from the way light interacts with the eye’s structure.

Green eyes result from a balance, a moderate amount of melanin layered with light scattering. Hazel eyes are more complex still. Uneven melanin distribution in the iris creates a mosaic of colour that can shift depending on the surrounding ambient light.

What have genes got to do with it?

The genetics of eye colour is just as fascinating.

For a long time, scientists believed a simple “brown beats blue” model, controlled by a single gene. Research now shows the reality is much more complex. Many genes contribute to determining eye colour. This explains why children in the same family can have dramatically different eye colours, and why two blue-eyed parents can sometimes have a child with green or even light brown eyes.

Eye colour also changes over time. Many babies of European ancestry are born with blue or grey eyes because their melanin levels are still low. As pigment gradually builds up over the first few years of life, those blue eyes may shift to green or brown.

In adulthood, eye colour tends to be more stable, though small changes in appearance are common depending on lighting, clothing, or pupil size. For example, blue-grey eyes can appear very blue, very grey or even a little green depending on ambient light. More permanent shifts are rarer but can occur as people age, or in response to certain medical conditions that affect melanin in the iris.

The real curiosities

Then there are the real curiosities.

Heterochromia, where one eye is a different colour from the other, or one iris contains two distinct colours, is rare but striking. It can be genetic, the result of injury, or linked to specific health conditions. Celebrities such as Kate Bosworth and Mila Kunis are well-known examples. Musician David Bowie’s eyes appeared as different colours because of a permanently dilated pupil after an accident, giving the illusion of heterochromia.

In the end, eye colour is more than just a quirk of genetics and physics. It’s a reminder of how biology and beauty intertwine. Each iris is like a tiny universe, rings of pigment, flecks of gold, or pools of deep brown that catch the light differently every time you look.

Eyes don’t just let us see the world, they also connect us to one another. Whether blue, green, brown, or something in-between, every pair tells a story that’s utterly unique, one of heritage, individuality, and the quiet wonder of being human.![]()

Davinia Beaver, Postdoctoral research fellow, Clem Jones Centre for Regenerative Medicine, Bond University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Giant stick insect species discovered in Australia

A large and previously unknown stick insect has been discovered in the misty forests of Far North Queensland — and it might just be Australia's heaviest insect.

The giant stick insect has been named Acrophylla alta, a nod to its high-altitude habitat in the Atherton Tablelands, ABC reported.

James Cook University Adjunct Professor Angus Emmott and south-east Queensland scientist Ross Coupland searched for the stick insect after they received a photograph of what they believed was an unknown species.

Despite its elusive nature, they managed to find a large female at an elevation above 900 metres between Millaa Millaa and Mount Hypipamee in the Wet Tropics World Heritage Area.

"We looked at its eggs after it laid some eggs and we were absolutely certain it was a new species," Mr Emmott said.

Two females have since been found, including one that a friend of Mr Emmott's found in a garden.

"They let it go afterwards, but they weighed it and photographed the weighing of it, and it was 44 grams," he said.

"I'm not sure exactly how to go about [verifying] that. I know the large burrowing cockroach was considered the heaviest insect, but it only gets into the mid-30 grams."Their findings have been published in the journal Zootaxa., Source: Article

Scientists develop real-time genome sequencing to combat deadly superbug

IANS Photo

IANS PhotoLizard Island on Australia's Great Barrier Reef faces alarming coral loss following 2024 bleaching

Scientists Reverse Parkinson’s Symptoms in Mice: ‘We were astonished by the success’

Australian scientists discover proteins that could help fight cancer, slow ageing

Australian researchers use a quantum computer to simulate how real molecules behave

When a molecule absorbs light, it undergoes a whirlwind of quantum-mechanical transformations. Electrons jump between energy levels, atoms vibrate, and chemical bonds shift — all within millionths of a billionth of a second.

These processes underpin everything from photosynthesis in plants and DNA damage from sunlight, to the operation of solar cells and light-powered cancer therapies.

Yet despite their importance, chemical processes driven by light are difficult to simulate accurately. Traditional computers struggle, because it takes vast computational power to simulate this quantum behaviour.

Quantum computers, by contrast, are themselves quantum systems — so quantum behaviour comes naturally. This makes quantum computers natural candidates for simulating chemistry.

Until now, quantum devices have only been able to calculate unchanging things, such as the energies of molecules. Our study, published this week in the Journal of the American Chemical Society, demonstrates we can also model how those molecules change over time.

We experimentally simulated how specific real molecules behave after absorbing light.

Simulating reality with a single ion

We used what is called a trapped-ion quantum computer. This works by manipulating individual atoms in a vacuum chamber, held in place with electromagnetic fields.

Normally, quantum computers store information using quantum bits, or qubits. However, to simulate the behaviour of the molecules, we also used vibrations of the atoms in the computer called “bosonic modes”.

This technique is called mixed qudit-boson simulation. It dramatically reduces how big a quantum computer you need to simulate a molecule.

We simulated the behaviour of three molecules absorbing light: allene, butatriene, and pyrazine. Each molecule features complex electronic and vibrational interactions after absorbing light, making them ideal test cases.

Our simulation, which used a laser and a single atom in the quantum computer, slowed these processes down by a factor of 100 billion. In the real world, the interactions take femtoseconds, but our simulation of them played out in milliseconds – slow enough for us to see what happened.

A million times more efficient

What makes our experiment particularly significant is the size of the quantum computer we used.

Performing the same simulation with a traditional quantum computer (without using bosonic modes) would require 11 qubits, and to carry out roughly 300,000 “entangling” operations without errors. This is well beyond the reach of current technology.

By contrast, our approach accomplished the task by zapping a single trapped ion with a single laser pulse. We estimate our method is at least a million times more resource-efficient than standard quantum approaches.

We also simulated “open-system” dynamics, where the molecule interacts with its environment. This is typically a much harder problem for classical computers.

By injecting controlled noise into the ion’s environment, we replicated how real molecules lose energy. This showed environmental complexity can also be captured by quantum simulation.

What’s next?

This work is an important step forward for quantum chemistry. Even though current quantum computers are still limited in scale, our methods show that small, well-designed experiments can already tackle problems of real scientific interest.

Simulating the real-world behaviour of atoms and molecules is a key goal of quantum chemistry. It will make it easier to understand the properties of different materials, and may accelerate breakthroughs in medicine, materials and energy.

We believe that with a modest increase in scale — to perhaps 20 or 30 ions — quantum simulations could tackle chemical systems too complex for any classical supercomputer. That would open the door to rapid advances in drug development, clean energy, and our fundamental understanding of chemical processes that drive life itself.![]()

Ivan Kassal, Professor of Chemical Physics, University of Sydney and Tingrei Tan, Research Fellow, Quantum Control Laboratory, University of Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Using tranquillisers on racehorses is ethically questionable and puts horses and riders at risk

Australia’s horse racing industry is in the spotlight after recent allegations of tranquilliser use on horses so they can be “worked” (exercised) between race days.

A recent ABC report stated workers in the Australian racing industry allegge horses are being routinely medicated for track work at the peril of rider and horse safety.

Using tranquillisers on horses during training and management may not be illegal but this could breach nationwide racing rules.

The prevalence of the practice is not clear but many industry insiders report it as common.

Racing Australia had “recently become aware” of the use of acepromazine for track work and had begun collecting data about the practice, but had not been made aware of any complaints or concerns.

What medications are horses given?

Horses may be given a low dose of a tranquilliser, most commonly acepromazine. This makes their behaviour easier to control in certain situations, such as when they’re being examined by a veterinarian.

This drug must be prescribed by an attending veterinarian, and it can calm unfriendly and apprehensive animals. This could assist with making excited, hyperactive horses easier to control and less likely to buck, rear or put people at risk of injury from uncontrolled flight responses.

But proprioception – the way horses feel the world around them, notably the ground beneath them – is likely to be compromised. So, from a work health and safety perspective, the risk of tripping and falling is front of mind.

Other risks to horses from acepromazine can include impaired blood clotting, lower blood pressure, respiratory depression and, in rare cases, permanent paralysis of the penis in male horses.

A dangerous combination

In the racing industry, tranquillisers are given to reduce the difficulties that come from riding and handling very fit, young horses that have been bred, fed and managed to be highly reactive and move at very high speeds.

This combination of selective breeding and only basic training can make them very difficult to control both during trackwork, when speeds of over 60 kilometres per hour can be reached, as well as during routine management.

Thoroughbreds’ diets, intensive management and relative lack of behavioural conditioning can be a dangerous combination.

The diets and confinement make them excitable and likely to take off; if they do, the lack of appropriate training makes them difficult to stop.

What makes race thoroughbreds hard to handle?

All horses have three fundamental needs – friends, forage and freedom, known as the “three F’s”.

Friends: horses have evolved to spend time with large mixed groups. They feel safer in these groups and this safety is highly valued: mutual grooming with preferred conspecifics (other equids) can calm them. In contrast, most stabled horses have no choice about who their neighbours are and can usually only have minimal physical interactions. Once out on the track, horses are highly motivated to stay with other horses and are more likely to be distracted rather than to attend to the rider.

Freedom: horses evolved to move for up to 70% of their day, which is essential for their welfare. In contrast, most racehorses, and indeed many other performance horses, often spend up to 23 hours a day confined in stables. Unfortunately, stabled horses are harder to train and more likely to buck. Prolonged confinement leads to many horses becoming more reactive, a state that increases the likelihood of injuries to riders.

Forage: horses are trickle feeders that graze on high-fibre, low-nutrient forages for up to 16 hours a day. In contrast, racehorses are fed high-energy diets that can be quickly consumed, leading to risk of digestive disturbances, such as gastric ulcers and long periods during which, confined to their stables, they have nothing to do.

Modern racehorse management and training often denies them access to these “three F’s”, which leads to behavioural problems that are then sometimes managed by tranquillising the horse.

Lastly, there’s the kind of work racehorses do.

High-intensity work increases the concentrations of adrenaline and cortisol to support the energy demands of the work. However, this increases the horse’s arousal and reduces their ability to attend to rider cues.

This can make them hard to control.

Collectively, these factors create horses that are not having their fundamental needs met. It’s no wonder that, once free of the confinement of their stables, they can become excited and hard to control, putting their riders and even themselves at risk of injury.

A band-aid solution

There is no textbook that advises vets on how to diagnose or treat horses that are hyperactive, nor are there any data on how horses can be safely tranquillised before being ridden.

However, a UK government data sheet for the most common equine tranquilliser globally, acepromazine maleate, states: “do not, in any circumstances, ride horses within the 36 hours following administration of the product”.

In Australia, racing trainers must keep records of all medications given to horses. Unfortunately, the veterinarians who supply this medication to trainers for use on racehorses are usually doing so without a specific diagnosis or treatment plan.

Routine use of tranquillisers is a band-aid solution to an industry-wide practice of confining, over-feeding and under-training fit, young horses that have been bred to run.

If this practice is ever policed, there will likely be enormous repercussions for the sustainability of racing.

As a first step to addressing this issue, the industry could commit to monitoring and publishing annual data on the routine use of tranquillisers.![]()

Paul McGreevy, Professor, School of Veterinary Science, University of Sydney and Cathrynne Henshall, Post-doctoral Fellow, School of Agricultural, Environmental and Veterinary Sciences, Charles Sturt University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Scientists Discover Mechanisms That Prevent Autoimmune Diseases and Win $600,000 Crafoord Prize

Man Lives for 100 Days with Artificial Titanium Heart in Successful New Trial

The Total Artificial Heart, made of titanium – credit BiVACOR

The Total Artificial Heart, made of titanium – credit BiVACORRenewables are cheap. So why isn’t your power bill falling?

Power prices are set to go up again even though renewables now account for 40% of the electricity in Australia’s main grid – close to quadruple the clean power we had just 15 years ago. How can that be, given renewables are the cheapest form of newly built power generation?

This is a fair question. As Australia heads for a federal election campaign likely to focus on the rising cost of living, many of us are wondering when, exactly, cheap renewables will bring cheap power.

The simple answer is – not yet. While solar and wind farms produce power at remarkably low cost, they need to be built where it’s sunny or windy. Our existing transmission lines link gas and coal power stations to cities. Connecting renewables to the grid requires expensive new transmission lines, as well as storage for when the wind isn’t blowing or the sun isn’t shining.

Notably, Victoria’s mooted price increase of 0.7% was much lower than other states, which would be as high as 8.9% in parts of New South Wales. This is due to Victoria’s influx of renewables – and good connections to other states. Because Victoria can draw cheap wind from South Australia, hydroelectricity from Tasmania or coal power from New South Wales through a good transmission line network, it has kept wholesale prices the lowest in the national energy market since 2020.

While it was foolish for the Albanese government to promise more renewables would lower power bills by a specific amount, the path we are on is still the right one.

That’s because most of our coal plants are near the end of their life. Breakdowns are more common and reliability is dropping. Building new coal plants would be expensive too. New gas would be pricier still. And the Coalition’s nuclear plan would be both very expensive and arrive sometime in the 2040s, far too late to help.

Renewables are cheap, building a better grid is not

The reason solar is so cheap and wind not too far behind is because there is no fuel. There’s no need to keep pipelines of gas flowing or trainloads of coal arriving to be burned.

But sun and wind are intermittent. During clear sunny days, the National Energy Market can get so much solar that power prices actually turn negative. Similarly, long windy periods can drive down power prices. But when the sun goes down and the wind stops, we still need power.

This is why grid planners want to be able to draw on renewable sources from a wide range of locations. If it’s not windy on land, there will always be wind at sea. To connect these new sources to the grid, though, requires another 10,000 kilometres of high voltage transmission lines to add to our existing 40,000 km. These are expensive and cost blowouts have become common. In some areas, strong objections from rural residents are adding years of delay and extra cost.

So while the cost of generating power from renewables is very low, we have underestimated the cost of getting this power to markets as well as ensuring the power can be “firmed”. Firming is when electricity from variable renewable sources is turned into a commodity able to be turned on or off as needed and is generally done by storing power in pumped hydro schemes or in grid-scale batteries.

In fact, the cost of transmission and firming is broadly offsetting the lower input costs from renewables.

Does this mean the renewable path was wrong?

At both federal and state levels, Labor ministers have made an error in claiming renewables would directly translate to lower power prices.

But consider the counterpoint. Let’s say the Coalition gets in, rips up plans for offshore wind zones and puts the renewable transition on ice. What happens then?

Our coal plants would continue to age, leading to more frequent breakdowns and unreliable power, especially during summer peak demand. Gas is so expensive as to be a last resort. Nuclear would be far in the future. What would be left? Quite likely, expensive retrofits of existing coal plants.

If we stick to the path of the green energy transition, we should expect power price rises to moderate. With more interconnections and transmission lines, we can accommodate more clean power from more sources, reducing the chance of price spikes and adding vital resilience to the grid. If an extreme weather event takes out one transmission line, power can still flow from others.

Storing electricity will be a game-changer

Until now, storing electricity at scale for later use hasn’t been possible. That means grid operators have to constantly match supply and demand. To cope with peak demand, such as a heatwave over summer, we have very expensive gas peaking plants which sit idle nearly all the time.

Solar has only made the challenge harder, as we get floods of solar at peak times and nothing in the evening when we use most of our power. Our coal plants do not deal well with being turned off and on to accommodate solar floods.

The good news is, storage is solving most of these problems. Being able to keep hours or even days of power stored in batteries or in elevated reservoirs at hydroelectric plants gives authorities much more flexibility in how they match supply and demand.

We will never see power “too cheap to meter”, as advocates once said of the nuclear industry. But over time, we should see price rises ease.

For our leaders and energy authorities, this is a tricky time. They must ensure our large-scale transmission line interconnectors actually get built, juggle the flood of renewables, ensure storage comes online, manage the exit of coal plants and try not to affect power prices. Pretty straightforward.![]()

Tony Wood, Program Director, Energy, Grattan Institute

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Second-Ever Elusive Night Parrot Egg Discovered in Australia Where it Had Been ‘Extinct’ for 100 Years

Ngururrpa Ranger Lucinda Gibson gently holding the unfertilised night parrot egg – credit: supplied by Ngururrpa Rangers.

Ngururrpa Ranger Lucinda Gibson gently holding the unfertilised night parrot egg – credit: supplied by Ngururrpa Rangers. Adult night parrots are ground-dwelling birds that fly – Photo by Steve Murphy

Adult night parrots are ground-dwelling birds that fly – Photo by Steve Murphy

It’s official: Australia’s ocean surface was the hottest on record in 2024

Australia’s sea surface temperatures were the warmest on record last year, according to a snapshot of the nation’s climate which underscores the perilous state of the world’s oceans.

The Bureau of Meteorology on Thursday released its annual climate statement for 2024 – the official record of temperature, rainfall, water resources, oceans, atmosphere and notable weather.

Among its many alarming findings were that sea surface temperatures were hotter than ever around the continent last year: a whopping 0.89°C above average.

Oceans cover more than 70% of Earth’s surface, and their warming is gravely concerning. It causes sea levels to rise, coral to bleach and Earth’s ice sheets to melt faster. Hotter oceans also makes weather on land more extreme and damages the marine life which underpins vital ocean ecosystems.

What the snapshot showed

Australia’s climate varies from year to year. That’s due to natural phenomena such as the El Niño and La Niña climate drivers, as well as human-induced climate change.

The bureau confirmed 2024 was Australia’s second-warmest year since national records began in 1910. The national annual average temperature was 1.46°C warmer than the long-term average (1961–90). Heatwaves struck large parts of Australia early in the year, and from September to December.

Average rainfall in Australia was 596 millimetres, 28% above the 30-year average, making last year the eighth-wettest since records began.

And annual sea surface temperatures for the Australian region were the warmest on record. Global sea surface temperatures in 2024 were also the warmest on record.

According to the bureau, Antarctic sea-ice extent was far below average, or close to record-lows, for much of the year but returned to average in December.

What caused the hot oceans?

It’s too early to officially attribute the ocean warming to climate change. But we do know greenhouse gas emissions are heating the Earth’s atmosphere, and oceans absorb 90% of this heat.

So we can expect human-induced climate change played a big role in warming the oceans last year. But shorter-term forces are at play, too.

The rare triple-dip La Niña Australia experienced from 2020 to 2023 brought cooler water from deep in the ocean up to the surface. It was like turning on the ocean’s air-conditioner.

But that pattern ended and Australia entered an El Niño in September 2023. It lasted about seven months, when the oscillation between El Niño and La Niña entered a neutral phase.

The absence of a La Niña meant cool water was no longer being churned up from the deep. Once that masking effect disappeared, the long-term warming trend of the oceans became apparent once more.

Water can store a lot more heat than air. In fact, just the top few metres of the ocean store as much heat as Earth’s entire atmosphere. Oceans take a long time to heat up and a long time to cool.

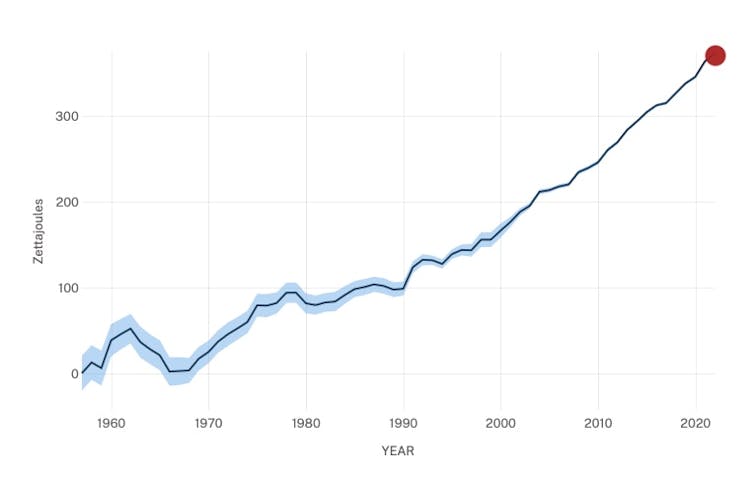

Heat at the ocean’s surface eventually gets pushed deeper into the water column and spreads across Earth’s surface in currents. The below chart shows how the world’s oceans have heated over the past 70 years. Changes in the world’s ocean heat content since 1955. NOAA/NCEI World Ocean Database

Changes in the world’s ocean heat content since 1955. NOAA/NCEI World Ocean Database

Why should we care about ocean warming?

Rapid warming of Earth’s oceans is setting off a raft of worrying changes.

It can lead to less nutrients in surface waters, which in turn leads to fewer fish. Warmer water can also cause species to move elsewhere. This threatens the food security and livelihoods of millions of people around the world.

Just last week, it was reported that tens of thousands of fish died off northwestern Australia due to a large and prolonged marine heatwave.

Warm water causes coral bleaching, as experienced on the Great Barrier Reef in recent decades. It also makes oceans more acidic, reducing the amount of calcium carbonate available for organisms to build shells and skeletons.

Warming oceans trigger sea level rise – both due to melt water from glaciers and ice sheets, and the fact seawater expands as it warms.

Hotter oceans are also linked to weather extremes, such as more intense cyclones and heavier rainfall. It’s likely the high annual rainfall Australia experienced in 2024 was in part due to warmer ocean temperatures.

What now?

As long as humans keep burning fossil fuels and pumping greenhouse gases into the atmosphere, the oceans will keep warming.

Unfortunately, the world is not doing a good job of shifting its emissions trajectory. As the bureau pointed out in its statement, concentrations of all major long-lived greenhouse gases in the atmosphere increased last year, including carbon dioxide and methane.

Prolonged ocean warming is driving changes in weather patterns and more frequent and intense marine heatwaves. This threatens ecosystems and human livelihoods. To protect our oceans and our way of life, we must transition to clean energy sources and cut carbon emissions.

At the same time, we must urgently expand ocean observing below the ocean’s surface, especially in under-studied regions, to establish crucial baseline data for measuring climate change impacts.

The time to act is now: to reduce emissions, support ocean research and help safeguard the future of our blue planet.![]()

Moninya Roughan, Professor in Oceanography, UNSW Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

To save Australia’s animals, scientists must count how many are left. But what if they’re getting it wrong?

Humans are causing enormous damage to the Earth, and about one million plant and animal species are now at risk of extinction. Keeping track of what’s left is vital to conserving biodiversity.

Biodiversity monitoring helps document changes in animal and plant populations. It tells us whether interventions, such as controlling feral predators, are working. It also helps experts decide if a species is at risk of extinction.

However, long-term biodiversity monitoring can be expensive and time consuming – and it is chronically underfunded. This means monitoring is either not done at all, or only done in a small part of the range of a species.

Our new research shows these limitations can produce an inaccurate picture of how a species is faring. This is a problem for conservation efforts, and Australia’s new “nature repair market”. It’s also a problem for Australia’s unique and vulnerable biodiversity.

How monitoring works

Biodiversity monitoring involves looking for a plant or animal species, or traces of it, and recording what was found, as well as when and where.

Depending on the species, scientists might physically count individual plants or animals, or review sound or video recordings. Or they might look for evidence of an animal’s presence, such as scats (poos).

But long-term monitoring programs can be challenging to maintain. Robust programs typically require money, and a lot of time and expertise. A lack of funding means monitoring programs are often short lived or conducted across a small geographic area.

Such limitations can mean the results do not reflect the trajectory of a species across its entire range. We decided to test how this problem might be playing out in Australia, with monitoring of birds.

What our study involved

Our new study focused on 18 common species of birds. We have monitored them (and hundreds of other bird species) for more than two decades across more than 570 sites in Australia’s southeast. The programs aimed to gauge how the birds responded to threats such as bushfires and logging, as well as conservation efforts such as vegetation restoration.

But we used the monitoring results for a different purpose. We wanted to know if different populations of the same species showed similar patterns of change. As a hypothetical example, did a group of crimson rosellas in one area increase in size at the same rate as a group of crimson rosellas living 150 kilometres away?

Answering this question is important. If all populations show the same pattern of change over time, then the trends from a single population would serve as a good indicator for other populations.

But if there are strong differences in patterns between populations, then a single monitoring program in the middle of a species’ range would not accurately indicate how that species is faring at the edge of its range, or overall.

The 18 bird species we examined in detail included – aside from the crimson rosella – the red wattlebird, grey shrike-thrush, superb fairy-wren and brown thornbill.

What we found

We discovered marked differences in how many individuals of a species were detected in different parts of its range. For example, some populations of the grey shrike thrush were stable, others increased, and yet another declined steeply.

We also wanted to determine if there were ways to predict which populations of a given species might be more likely to be increasing or decreasing.

For example, if the monitoring program was at the centre of a species’ distribution – where the climate and food availability was optimal – a population there might be expected to be increasing faster than populations at the edge of that species’ distribution, where conditions could be less suitable.

Surprisingly, however, we found no evidence to support this hypothesis.

We also thought particular traits of a bird species, such as diet or body size, might affect whether numbers were rising, falling, or steady.

For instance, small bush birds might be more likely to decline due to being killed by predators or losing the competition for food to larger birds. Conversely, we expected that larger birds might be more resilient and their numbers more likely to increase. But again, we found no evidence of this.

These results indicate it is difficult to predict in advance which populations of a species will be declining versus those that are increasing or stable. It means scientists can’t reliably use such predictions when determining which parts of a species’ distribution should be monitored.

Our findings suggest that to get an accurate picture of a species’ overall trend, monitoring should cover, at a minimum, several populations of that species in different parts of its overall distribution. Importantly, this information can help identify those locations where populations are declining and conservation programs are needed.

And where a species is declining everywhere it is monitored, we should be extremely concerned. It shows a need for decisive conservation action. A species should not be allowed to go extinct while it is being observed, as occurred with the Christmas Island Pipistrelle bat.

Getting it right

Biodiversity monitoring in Australia is, overall, extremely poor. However, some excellent biodiversity monitoring programs do exist.

They include one on native mammals in south-west Western Australia and another on waterbirds across large parts of inland Australia. These programs demonstrate what’s possible when funding and resources are adequate.

The federal government is currently setting up Australia’s new “nature repair market”. Under the scheme, those who run projects to restore and protect the environment are rewarded financially. But how will we know if these projects are successful and biodiversity is increasing? Only monitoring can answer this question.

If the nature repair market is to be credible, Australia must markedly lift its game on biodiversity monitoring. Otherwise, environmental gains under the scheme may be purely fictional.![]()

David Lindenmayer, Professor, Fenner School of Environment and Society, Australian National University; Benjamin Scheele, Research Fellow in Ecology, Australian National University; Elle Bowd, Research Fellow, Fenner School of Environment and Society, Australian National University, and Maldwyn John Evans, Senior Research Fellow, Fenner School of Environment and Society, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.