Sagumai et al. / Journal of Fish Biology, 2025

Sagumai et al. / Journal of Fish Biology, 2025Elusive Sailback Shark Rediscovered After 50 Years

Sagumai et al. / Journal of Fish Biology, 2025

Sagumai et al. / Journal of Fish Biology, 2025South Africa’s great white sharks are changing locations – they need to be monitored for beach safety and conservation

In Cape Town, skilled “shark spotters” documented a peak of over 300 great white shark sightings across eight beaches in 2011, but have recorded no sightings since 2019. These declines have sparked concerns about the overall conservation status of the species.

Conserving great white sharks is vital because they have a pivotal role in marine ecosystems. As top predators, they help maintain the health and balance of marine food webs. Their presence influences the behaviour of other marine animals, affecting the entire ecosystem’s structure and stability.

Marine biologists like us needed to know whether the decline in shark numbers in the Western Cape indicated changes in the whole South African population or whether the sharks had moved to a different location.

To investigate this problem, we undertook an extensive study using data collected by scientists, tour operators and shore anglers. We examined the trends over time in abundance and shifts in distribution across the sharks’ South African range.

Our investigation revealed significant differences in the abundance at primary gathering sites. There were declines at some locations; others showed increases or stability. Overall, there appears to be a stable trend. This suggests that white shark numbers have remained constant since they were given protection in 1991.

Looking at the potential change in the distribution of sharks between locations, we discovered a shift in human-shark interactions from the Western Cape to the Eastern Cape. More research is required to be sure whether the sharks that vanished from the Western Cape are the same sharks documented along the Eastern Cape.

The stable population of white sharks is reassuring, but the distribution shift introduces its own challenges, such as the risk posed by fisheries, and the need for beach management. So there is a need for better monitoring of where the sharks are.

Factors influencing shark movements

We recorded the biggest changes between 2015 and 2020. For example, at Seal Island, False Bay (Western Cape), shark sightings declined from 2.5 sightings per hour in 2005 to 0.6 in 2017. Shifting eastward to Algoa Bay, in 2013, shore anglers caught only six individual sharks. By 2019, this figure had risen to 59.

The changes at each site are complex, however. Understanding the patterns remains challenging.

These predators can live for more than 70 years. Each life stage comes with distinct behaviours: juveniles, especially males, tend to stay close to the coastline, while sub-adults and adults, particularly females, venture offshore.

Environmental factors like water temperature, lunar phase, season and food availability further influence their movement patterns.

Changes in the climate and ocean over extended periods might also come into play.

As adaptable predators, they target a wide range of prey and thrive in a broad range of temperatures, with a preference for 14–24°C. Their migratory nature allows them to seek optimal conditions when faced with unfavourable environments.

Predation of sharks by killer whales

The movement complexity deepens with the involvement of specialist killer whales with a taste for shark livers. Recently, these apex predators have been observed preying on white, sevengill and bronze whaler sharks.

Cases were first documented in 2015 along the South African coast, coinciding with significant behavioural shifts in white sharks within Gansbaai and False Bay.

Although a direct cause-and-effect link is not firmly established, observations and tracking data support the notion of a distinct flight response among white sharks following confirmed predation incidents.

More recently, it was clear that in Mossel Bay, when a killer whale pod killed at least three white sharks, the remaining sharks were prompted to leave the area.

Survival and conservation of sharks

The risk landscape for white sharks is complex. A study published in 2022 showed a notable overlap of white sharks with longline and gillnet fisheries, extending across 25% of South Africa’s Exclusive Economic Zone. The sharks spent 15% of their time exposed to these fisheries.

The highest white shark catches were reported in KwaZulu-Natal, averaging around 32 per year. This emphasised the need to combine shark movement with reliable catch records to assess risks to shark populations.

As shark movement patterns shift eastward, the potential change in risk must be considered. Increased overlap between white sharks, shark nets, drumlines (baited hooks) and gillnets might increase the likelihood of captures.

Beach safety and management adaptation

Although shark bites remain a low risk, changing shark movements could also influence beach safety. The presence of sharks can influence human activities, particularly in popular swimming and water sports areas. Adjusting existing shark management strategies might be necessary as distributions change.

Increased signage, temporary beach closures, or improved education about shark behaviour might be needed.

In Cape Town, for example, shark spotters have adjusted their efforts on specific beaches. Following two fatal shark incidents in 2022, their programme expanded to Plettenberg Bay. Anecdotal evidence highlights additional Eastern Cape locations where surfers and divers encounter more white sharks than before.

Enhanced monitoring and long-term programmes

Further research is required to understand the factors behind the movements of sharks and their impact on distribution over space and time. Our study underscores the importance of standardising data collection methods to generate reliable abundance statistics across their entire range. Other countries suffer from the same problem.

Additionally, we propose establishing long-term monitoring programmes along the Eastern Cape and continuing work to reduce the number of shark deaths.

Sarah Waries, a master’s student and CEO of Shark Spotters in Cape Town, contributed to this article.![]()

Alison Kock, Marine Biologist, South African National Parks (SANParks); Honorary Research Associate, South African Institute for Aquatic Biodiversity (SAIAB), South African Institute for Aquatic Biodiversity; Alison Towner, Marine biologist, Rhodes University; Heather Bowlby, Research Lead, Fisheries and Oceans Canada; Matt Dicken, Adjunct Professor of Marine Biology, Nelson Mandela University, and Toby Rogers, PhD Candidate, University of Cape Town

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Sharks may show the way for humans to re-grow teeth

Shark Net: Dr. Barbara Block/TOPP release great app to track California's white sharks

TOPP to discover many of the secrets involving the migration patterns of these large and critically important animals. It was TOPP that coined the phrase "White Shark Cafe" to describe where great white sharks from California and Mexico migrate to in the Pacific Ocean. One particularly important finding regarding these migration patterns was the possible explanation for the seasonal nature of the sharks' sojourns: Mid-Pacific upwellings which bring nutrients that feed the food chain and ultimately replenish the larger fish that the sharks feed on. Cyclical weather and ocean movement patterns produce these upwellings - and as climate change continues to present itself, there is always the possibility of shifts in the upwelling cycle that could have unknown consequences for these animals. Whenever I am called upon to speak about sharks, these fascinating migration patterns are always a topic I include as I am guaranteed they will mesmerize my audience. So, thank you, Dr. Block! While Internet users can monitor the ongoing activities of TOPP through its website, it's now possible to carry it with you on your iPhone or iPad. Shark Net - Predators of the Blue Serengeti is available fromiTunes at no charge (as in free!) and provides a range of features on the cataloging and whereabouts of those most iconic of California ocean predators, the great white shark. Users can get updates on the latest monitoring of sharks, pinpoint the location of the tracking buoys that gather the data, and get biographies, photos, and videos about many of the sharks that frequent California's waters. There are other apps available that provide white shark tracking info but this is thedefinitive app for monitoring the white sharks that ply the waters off California's coast - and beyond, thanks to those incredible migration patterns. In a recent interview for U.K.'s The Guardian, Dr. Block explained her use of the term "Blue Serengeti" to describe California's coastal waters and the large migration patterns that occur within it. "White sharks and tuna travel for thousands of miles before returning to the same hot spot just as salmon do when they return to the same stream. These journeys are the marine equivalent of wildebeest migrations that take place on the Serengeti plain in Africa. That is why I call this part of the Californian coast the Blue Serengeti." "Everyone knows about watering holes on the Serengeti even though most of us have never been there. We can just close our eyes and see the zebras, the elephants and the hyenas. We want to do the same for the migration hot spots we have found off the coast of California." Dr. Block and TOPP are setting new standards for ocean animal tracking, expanding on the various GPS and satellite tracking methods (which can sometimes provide data intermittently) to include cutting-edge, round-the-clock monitoring technology using monitoring networks or even self-contained, solar-powered tracking stations like Wave Glider that travels the currents along the California coast. Through the efforts of TOPP and consumer apps like Shark Net, Dr. Block hopes to bring the hidden complexity of our ocean planet to a wider audience. Humankind's curiosity makes it look outward, and that has lead us into the stars. But there is a whole world to be discovered starting right at the shoreline. "Human technology has made it to Mars. We are transmitting gorgeous pictures from it. Yet we have not explored our own planet. Two-thirds of it is covered with oceans that are still mysterious places. We are trying to hook people up to what is going on out there now and get them to realize that it could all be lost if we did not do something to protect it. Ultimately, I want to create a world heritage site here. Wiring up the oceans, as we are doing, is our way to get people to understand the importance of these places."Source: RTSea

TOPP to discover many of the secrets involving the migration patterns of these large and critically important animals. It was TOPP that coined the phrase "White Shark Cafe" to describe where great white sharks from California and Mexico migrate to in the Pacific Ocean. One particularly important finding regarding these migration patterns was the possible explanation for the seasonal nature of the sharks' sojourns: Mid-Pacific upwellings which bring nutrients that feed the food chain and ultimately replenish the larger fish that the sharks feed on. Cyclical weather and ocean movement patterns produce these upwellings - and as climate change continues to present itself, there is always the possibility of shifts in the upwelling cycle that could have unknown consequences for these animals. Whenever I am called upon to speak about sharks, these fascinating migration patterns are always a topic I include as I am guaranteed they will mesmerize my audience. So, thank you, Dr. Block! While Internet users can monitor the ongoing activities of TOPP through its website, it's now possible to carry it with you on your iPhone or iPad. Shark Net - Predators of the Blue Serengeti is available fromiTunes at no charge (as in free!) and provides a range of features on the cataloging and whereabouts of those most iconic of California ocean predators, the great white shark. Users can get updates on the latest monitoring of sharks, pinpoint the location of the tracking buoys that gather the data, and get biographies, photos, and videos about many of the sharks that frequent California's waters. There are other apps available that provide white shark tracking info but this is thedefinitive app for monitoring the white sharks that ply the waters off California's coast - and beyond, thanks to those incredible migration patterns. In a recent interview for U.K.'s The Guardian, Dr. Block explained her use of the term "Blue Serengeti" to describe California's coastal waters and the large migration patterns that occur within it. "White sharks and tuna travel for thousands of miles before returning to the same hot spot just as salmon do when they return to the same stream. These journeys are the marine equivalent of wildebeest migrations that take place on the Serengeti plain in Africa. That is why I call this part of the Californian coast the Blue Serengeti." "Everyone knows about watering holes on the Serengeti even though most of us have never been there. We can just close our eyes and see the zebras, the elephants and the hyenas. We want to do the same for the migration hot spots we have found off the coast of California." Dr. Block and TOPP are setting new standards for ocean animal tracking, expanding on the various GPS and satellite tracking methods (which can sometimes provide data intermittently) to include cutting-edge, round-the-clock monitoring technology using monitoring networks or even self-contained, solar-powered tracking stations like Wave Glider that travels the currents along the California coast. Through the efforts of TOPP and consumer apps like Shark Net, Dr. Block hopes to bring the hidden complexity of our ocean planet to a wider audience. Humankind's curiosity makes it look outward, and that has lead us into the stars. But there is a whole world to be discovered starting right at the shoreline. "Human technology has made it to Mars. We are transmitting gorgeous pictures from it. Yet we have not explored our own planet. Two-thirds of it is covered with oceans that are still mysterious places. We are trying to hook people up to what is going on out there now and get them to realize that it could all be lost if we did not do something to protect it. Ultimately, I want to create a world heritage site here. Wiring up the oceans, as we are doing, is our way to get people to understand the importance of these places."Source: RTSeaHere Are The Most Vicious Fish Of All Time

.jpg) Amazon, the black piranha, and describes the underlying functional morphology of the jaws that allows this creature to bite with a force more than 30 times greater than its weight. The powerful bite is achieved primarily due to the large muscle mass of the black piranha’s jaw and the efficient transmission of its large contractile forces through a highly modified jaw-closing lever. The expedition was organized and filmed by National Geographic. A subsequent program called Megapiranha aired on the National Geographic Channel featured the expedition and focused on the creature that existed millions of years ago. “It was very exciting to participate in this project, travel one more time to the Amazon to be able to directly measure bite forces in the wild,” said Dr. Orti. “I learned a lot of biomechanics from my colleagues while collecting valuable specimens for my own research.” The authors also reconstructed the bite force of the megapiranha, showing that for its relatively diminutive body size, the bite of this fossil piranha dwarfed that of other extinct mega-predators, including the whale-eating shark and the Devonian placoderm. Research at the Ortí lab at GW continues to focus on reconstructing the genealogical tree of fishes including piranhas based on genomic data. Scientific Reports is a primary research publication from the publishers of Nature, covering all areas of the natural sciences. Contacts and sources: Rice Hall, George Washington University, Source: Nano Patents And Innovations

Amazon, the black piranha, and describes the underlying functional morphology of the jaws that allows this creature to bite with a force more than 30 times greater than its weight. The powerful bite is achieved primarily due to the large muscle mass of the black piranha’s jaw and the efficient transmission of its large contractile forces through a highly modified jaw-closing lever. The expedition was organized and filmed by National Geographic. A subsequent program called Megapiranha aired on the National Geographic Channel featured the expedition and focused on the creature that existed millions of years ago. “It was very exciting to participate in this project, travel one more time to the Amazon to be able to directly measure bite forces in the wild,” said Dr. Orti. “I learned a lot of biomechanics from my colleagues while collecting valuable specimens for my own research.” The authors also reconstructed the bite force of the megapiranha, showing that for its relatively diminutive body size, the bite of this fossil piranha dwarfed that of other extinct mega-predators, including the whale-eating shark and the Devonian placoderm. Research at the Ortí lab at GW continues to focus on reconstructing the genealogical tree of fishes including piranhas based on genomic data. Scientific Reports is a primary research publication from the publishers of Nature, covering all areas of the natural sciences. Contacts and sources: Rice Hall, George Washington University, Source: Nano Patents And InnovationsSharks Are Color Blind: new study shows they live in a world of contrast

According to a new study by scientists from Australia, sharks are color blind. This puts them in the same category as whales and dolphins as sea creatures that may have had color vision at one time but evolved to a black and white world, perhaps as a more effective means of hunting. Previous studies of several species of rays, part of the same general family as sharks, were found to have several types of ospins or light sensitive proteins in the photoreceptors of their retinas which provide them with the ability to see in color. But studies of wobbegong sharks showed them to not have the necessary levels of ospins for color, only black and white. Dr. Susan Theiss, University of Queensland (yes, we're related - she is my niece), and her colleagues studied two different species of wobbegong sharks; each of which prefer different levels of depth in the sea as their normal habitat. Because of those differences in depth, the vision of the two species is more sensitive to different wavelengths of light. Each species is better attuned to the type of light that predominantly penetrates their environment. One wobbegong shark species preferred deeper water where it is penetrated by shorter wavelengths - a bluish kind of light. Sharks in shallower water can be more sensitive to red or green spectrums of light. Color blind as they are then, sharks live in a world of contrast. Their other senses of sound and scent can aid them in their search for prey then, at some point, contrasting visual stimuli kicks in, and at close range sensing electrical impulses can come into play. Sometimes color can be a distraction and can prevent the shark from staying focused on a potential target. Color exists in nature for a variety of reasons and in some environments it can actually act as a kind of camouflage. Oddly enough, as a filmmaker, I typically use a black and white viewfinder with my camera as it can often provide a sharper image for focusing purposes. Playing off that sense of visual contrast, it might be possible to help keep sharks from becoming accidental bycatch by camouflaging or making hooks less visually interesting. And the same could possibly be said for surfers who provide considerable contrast (as does a seal) in their black wetsuits. "If we can use this knowledge to design longline fishing lures that are less visible to sharks then we will be able to reduce the amount of shark bycatch. We may also be able to make wetsuits less attractive, and make the water safer for surfers and divers," says co-author Associate professor Nathan Hart of the University of Western Australia and reported in Australia's ABC Science.Source: RTSea

According to a new study by scientists from Australia, sharks are color blind. This puts them in the same category as whales and dolphins as sea creatures that may have had color vision at one time but evolved to a black and white world, perhaps as a more effective means of hunting. Previous studies of several species of rays, part of the same general family as sharks, were found to have several types of ospins or light sensitive proteins in the photoreceptors of their retinas which provide them with the ability to see in color. But studies of wobbegong sharks showed them to not have the necessary levels of ospins for color, only black and white. Dr. Susan Theiss, University of Queensland (yes, we're related - she is my niece), and her colleagues studied two different species of wobbegong sharks; each of which prefer different levels of depth in the sea as their normal habitat. Because of those differences in depth, the vision of the two species is more sensitive to different wavelengths of light. Each species is better attuned to the type of light that predominantly penetrates their environment. One wobbegong shark species preferred deeper water where it is penetrated by shorter wavelengths - a bluish kind of light. Sharks in shallower water can be more sensitive to red or green spectrums of light. Color blind as they are then, sharks live in a world of contrast. Their other senses of sound and scent can aid them in their search for prey then, at some point, contrasting visual stimuli kicks in, and at close range sensing electrical impulses can come into play. Sometimes color can be a distraction and can prevent the shark from staying focused on a potential target. Color exists in nature for a variety of reasons and in some environments it can actually act as a kind of camouflage. Oddly enough, as a filmmaker, I typically use a black and white viewfinder with my camera as it can often provide a sharper image for focusing purposes. Playing off that sense of visual contrast, it might be possible to help keep sharks from becoming accidental bycatch by camouflaging or making hooks less visually interesting. And the same could possibly be said for surfers who provide considerable contrast (as does a seal) in their black wetsuits. "If we can use this knowledge to design longline fishing lures that are less visible to sharks then we will be able to reduce the amount of shark bycatch. We may also be able to make wetsuits less attractive, and make the water safer for surfers and divers," says co-author Associate professor Nathan Hart of the University of Western Australia and reported in Australia's ABC Science.Source: RTSeaShark's Sense of Smell: scientist sniffs out the subtleties of acute sense

We have long heard about a shark's acute sense of smell. It's ability to detect the odors or scents given off by an injured fish was long considered one of a shark's primary tools in its predator tool kit. But just how sensitive is it? With currents or water motion moving odors around, just how does a shark sense a smell and then begin tracking it to its source? Dr. Jelle Atema has been studying sharks for some 20 years, working with the Boston University and the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. He has spent considerable time investigating just how sharks utilize their sense of smell to their best advantage. Reporting in BU Today, Susan Seligson writes of Dr. Atema's work with smooth dogfish, a small shark that is often found in the U.S. northeast (BTW: And one that has been severely hit by commercial shark fishing operations). Using controlled plumes of odors like squid scent in a long observation tank, he is unlocking many of the secret subtleties as to how a shark senses odor and tracks it to its source. Often we think of sharks as sensing the smell given off by an injured animal. That may be true but, when hunting, sharks are attracted to the odors of familiar prey, injured or otherwise. “All animals give off some kind of body odor,” says Atema.“The science here is to understand how odor is dispersed into the water, and how many molecules does a shark need in his nose to track that odor.” Dr. Atema's experiments have also provided new insight as to how a shark responds to odors and how they just where to go to get to the source. As reported in BU Today, "Working along with Jayne Gardiner at the University of South Florida, in Tampa, Atema’s most recent discovery is that sharks are guided by the nostril that first detects the prey’s odor, rather than orienting themselves based on which nostril senses the greater odor concentration. The finding—that smell reaches one nostril before the other, signaling whether to veer left or right—means that sharks can decipher very quickly, a matter of seconds as opposed to minutes, where their next meal is, no matter how chaotic the dispersed odor plume. Before this discovery, published in Current Biology, scientists had long believed that sharks’ sense of smell was a function of the plume’s surface area—the bigger the plume, the easier it would be for sharks to smell it." In some respects, the ocean is a very smelly place, full of scents or odors of hundreds of different organisms and at varying strengths or intensities. Bombarded with all these stimuli, sharks can amazingly sort it all out and, along with its other senses, be the efficient predator that it is. Source: RTSea

Robotic shark spotter tested

'Bullingdon Club' dolphins form elite societies and cliques, scientists find

Wild bottlenose dolphins bond over their use of tools, with distinct cliques and classes forming over decades as a result of their skills, scientists have found. The communities, which have been compared with societies such as the Bullingdon Club in humans, mean the aquatic animals share their knowledge only with those in their own circle, passing it down the family line. The findings mean the traits of “inclusive inheritability” and culture are no longer considered exclusive to human beings. Observing wild dolphins in Shark Bay, Australia, researchers from Georgetown University used hunting tools as a marker of dolphin societal habits. Noticing some dolphins in the area used a sponge to protect their beaks while hunting, they attempted to discover why the practice had not spread. Source: The Coming Crisis

From Shark Teeth To Shark Cage: some interesting items in the news

regularly, dental protection should not be a problem for sharks.” So, sharks have built-in cavity protection. And, as the professor mentioned, they replace their teeth regularly. A shark can contain as many as several hundred teeth in it's jaw at any one time, with rows of fresh new teeth ready to come to the fore as older teeth are pushed out. Which brings me to the second interesting shark item. Many of you have seen images of the white sharks at Seal Beach, South Africa leaping out of the water attempting to either bite down on an unsuspecting seal - or a seal decoy placed in the water by crews hoping to grab some spectacular video or still photos. South Africa's Chris Fallows has built a respected career out of documenting white sharks going airborne with videos like the "Air Jaws" series and some amazing photographs. Australia's The Daily Telegraph ran a brief article on Seal Beach with photographer Dan Callister taking his own memorable photographs of airborne white sharks. As dramatic as his shots were, what caught my eye in several rapid-fire images of a shark grabbing a seal decoy was the clear evidence

Are Sharks Social?: Australian researcher studies social interaction of Port Jackson sharks

A great white shark seems to keep its distance from its fellow white sharks. Even when I have had the opportunity to have as many as five white sharks circling around me, they still keep a respectable distance from each other and rarely came close to each other. Then on the other hand, you have hammerhead sharks that can be seen swimming in large schools. Lemon sharks or various types of reef sharks congregating in the tens and sometimes hundreds. And I have seen seasonal congregations of up to 4-5 foot leopard sharks and guitarfish in Southern California, presumably part of a breeding behavior. The social interactions of sharks is not well understood. Each species has its own type of behavior and while the general public thinks of sharks as somewhat solitary (which they often can be), in reality it is more likely a very complex relationship that revolves around feeding, breeding, and a predator's sense of territoriality (ie: survival). In Australia, one researcher is specifically focusing his efforts on understanding the social behavior of sharks. Working in conjunction with the Taronga Zoo in Sydney, Australia, Nathan Bass intends to study the patterns of interaction between Port Jackson sharks, a smaller, predominantly bottom-feeding species similar to the horn shark found along the Pacific coast of the U.S. “Port Jackson sharks have some really interesting interactions,” says Bass. “These types of sharks can be solitary, but they often occur in large groups around breeding time. They are apparently social while resting and seem to favour their resting sites, frequently with more than 30 individual sharks recorded together in one area alone.” Bass will be attaching acoustic transmitters, known as "tags," to several sharks to track their movements. Tags have long been used in shark research often to study the animal's regional hunting movements or longer migratory journeys. By attaching tags to a large number of Port Jackson sharks, Bass hopes to be able to correlate their movements and possible interactions with seasonal events such as known breeding periods to determine possible social behavioral patterns. “What we’d like to find out is whether Port Jackson sharks are frequently congregating with the same individuals for social reasons, and if they are, whether they prefer to socialise with individuals of the same sex and size or rather with individuals they’re related to,” said Bass.understanding of the social behavior An of one species of shark does not necessarily open the floodgates of enlightenment regarding sharks as a whole. But it is a solid first step and provides a sort of baseline with a set of behavioral assumptions that can be tested with other species. Insight into the social behavior patterns of sharks, no matter how social or anti-social these animals prove to be, will provide us with a better understanding as to their role in the maintenance of a healthy marine ecosystem and what the implications are with the loss of one or more of these important predators within a specific area. Source: RTSea Blog

A great white shark seems to keep its distance from its fellow white sharks. Even when I have had the opportunity to have as many as five white sharks circling around me, they still keep a respectable distance from each other and rarely came close to each other. Then on the other hand, you have hammerhead sharks that can be seen swimming in large schools. Lemon sharks or various types of reef sharks congregating in the tens and sometimes hundreds. And I have seen seasonal congregations of up to 4-5 foot leopard sharks and guitarfish in Southern California, presumably part of a breeding behavior. The social interactions of sharks is not well understood. Each species has its own type of behavior and while the general public thinks of sharks as somewhat solitary (which they often can be), in reality it is more likely a very complex relationship that revolves around feeding, breeding, and a predator's sense of territoriality (ie: survival). In Australia, one researcher is specifically focusing his efforts on understanding the social behavior of sharks. Working in conjunction with the Taronga Zoo in Sydney, Australia, Nathan Bass intends to study the patterns of interaction between Port Jackson sharks, a smaller, predominantly bottom-feeding species similar to the horn shark found along the Pacific coast of the U.S. “Port Jackson sharks have some really interesting interactions,” says Bass. “These types of sharks can be solitary, but they often occur in large groups around breeding time. They are apparently social while resting and seem to favour their resting sites, frequently with more than 30 individual sharks recorded together in one area alone.” Bass will be attaching acoustic transmitters, known as "tags," to several sharks to track their movements. Tags have long been used in shark research often to study the animal's regional hunting movements or longer migratory journeys. By attaching tags to a large number of Port Jackson sharks, Bass hopes to be able to correlate their movements and possible interactions with seasonal events such as known breeding periods to determine possible social behavioral patterns. “What we’d like to find out is whether Port Jackson sharks are frequently congregating with the same individuals for social reasons, and if they are, whether they prefer to socialise with individuals of the same sex and size or rather with individuals they’re related to,” said Bass.understanding of the social behavior An of one species of shark does not necessarily open the floodgates of enlightenment regarding sharks as a whole. But it is a solid first step and provides a sort of baseline with a set of behavioral assumptions that can be tested with other species. Insight into the social behavior patterns of sharks, no matter how social or anti-social these animals prove to be, will provide us with a better understanding as to their role in the maintenance of a healthy marine ecosystem and what the implications are with the loss of one or more of these important predators within a specific area. Source: RTSea BlogSouth Carolina Bull Shark

very likely a bull shark. Bull sharks are also one of the more aggressive sharks. Aggressive in that, when on the hunt, they do not rely on a single massive bite, like a white shark will do to a seal (or a mistaken swimmer). Instead, the bull shark will hunt large prey with repeated bites. This has been borne out by reports of swimmers or surfers who, when attacked by a bull shark, found that it would give chase and bite repeatedly in a rather tenacious, never-give-up manner. While a bull shark, like all sharks, do not single out humans as a specific prey, it is this determined behavior by the bull shark that puts it in the top four of most dangerous sharks (the other three being, white sharks, tiger sharks, and oceanic white tips). I have had the opportunity to get up close with a variety of shark species and the bull shark is the one that draws my utmost attention. After Sarah lost her catch in such a spectacular fashion, her fiance and stepfather contemplated taking their 10-foot boat out on the water to track down the shark, but after a few minutes on the water, they rethought the matter. "We need a bigger boat and a bigger net," said Van Hughes, Sarah's stepfather. "We need a bigger boat." Now, where have I heard that before. . . . According to Dan Abel, shark researcher at the Coastal Carolina University, "It's not like just because we saw this shark yesterday that was just chasing this fish that was struggling on a line means that everything is going haywire. They're out there all the time anyway. It just so happens that this one opportunity a person caught it on film." Just another apex predator doing its thing.Source: RTSea Blog

very likely a bull shark. Bull sharks are also one of the more aggressive sharks. Aggressive in that, when on the hunt, they do not rely on a single massive bite, like a white shark will do to a seal (or a mistaken swimmer). Instead, the bull shark will hunt large prey with repeated bites. This has been borne out by reports of swimmers or surfers who, when attacked by a bull shark, found that it would give chase and bite repeatedly in a rather tenacious, never-give-up manner. While a bull shark, like all sharks, do not single out humans as a specific prey, it is this determined behavior by the bull shark that puts it in the top four of most dangerous sharks (the other three being, white sharks, tiger sharks, and oceanic white tips). I have had the opportunity to get up close with a variety of shark species and the bull shark is the one that draws my utmost attention. After Sarah lost her catch in such a spectacular fashion, her fiance and stepfather contemplated taking their 10-foot boat out on the water to track down the shark, but after a few minutes on the water, they rethought the matter. "We need a bigger boat and a bigger net," said Van Hughes, Sarah's stepfather. "We need a bigger boat." Now, where have I heard that before. . . . According to Dan Abel, shark researcher at the Coastal Carolina University, "It's not like just because we saw this shark yesterday that was just chasing this fish that was struggling on a line means that everything is going haywire. They're out there all the time anyway. It just so happens that this one opportunity a person caught it on film." Just another apex predator doing its thing.Source: RTSea BlogManta Rays: new study tracks their movements off Yucatan

RTSea: While marine advocates fret over the plight of sharks and their fate at the hands of commercial fishermen, another of the shark's relatives is heading into perilous waters: the majestic and graceful Manta Ray. Given the unfortunate nickname "devil fish" by local fishermen, the manta ray, which can attain an enormous 25-foot wingspan, is a filter-feeder and completely harmless to humans (it does not have a stinger like other rays). Similar to baleen whales, the manta ray draws water through its mouth and, as it passes through its gills, structures called gill rakers strain zooplankton from the water. What has put the manta ray at risk - it is currently listed as "vulnerable" to extinction by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) - is that they are hunted in some quarters for those gill rakers, a favorite of traditional Chinese medicine, and they are also caught as accidental bycatch. Part of the elasmobranch subclass that includes sharks, skates, and rays, the manta ray, like their relatives, does not have a high reproductive rate. So, they are not well-prepared to withstand high losses.However, there's much we do not know about these large rays that are so popular with scuba divers and snorklers in several tropical resort locations, representing not only a threatened species but a tourism generator as well. To fill the gap in our knowledge, a recent study which was just published in PLoS One used satellite tags, the ones often used on sharks and other pelagic fish, to learn more about the movement patterns of manta rays. Organized by the Wildlife Conservation Society, UK's University of Exeter, and the Mexican government, the study involved tagging six manta rays - four females, one male, and one juvenile - over a 13-day period off the coast of the Yucatan Peninsula. In that approximate two week period, the manta rays mostly stayed within 200 miles of the shoreline but did travel a good distance. “The satellite tag data revealed that some of the rays traveled more than 1,100 kilometers during the study period,” said Dr. Matthew Witt of the University of Exeter’s Environment and Sustainability Institute. “The rays spent most

of their time traversing coastal areas plentiful in zooplankton and fish eggs from spawning events.” Of concern was the fact that, with the rays not necessarily staying centralized to one area but more on the prowl for waters rich in zooplankton, they spent a considerable amount of time outside the boundaries of marine protected areas and, by doing so, putting themselves at risk from commercial fishing, being caught in nets accidentally, and even exposing themselves to the risk of being struck by large ships. Less than 12 percent of the locations were the tagged animals were tracked were within marine protected areas. “Almost nothing is known about the movements and ecological needs of the manta ray, one of the ocean’s largest and least-known species,” said Dr. Rachel Graham, lead author on the study and director of the Wildlife Conservation Society's Gulf and Caribbean Sharks and Rays Program. “Our real-time data illuminate the previously unseen world of this mythic fish and will help to shape management and conservation strategies for this species.” We can only hope that this and other future studies will provide a base of knowledge that will motivate governments and international agencies to take steps to arrest the apparent decline in manta ray populations. All filter-feeders play a role in maintaining the proper balance in zooplankton and other microscopic marine animals. Were we to lose the manta ray, we would be faced with unknown consequences. Source: RTSea

Thresher Shark Airborne: researcher takes remarkable pix of shark leaping

RTSea: With an elongated upper lobe of its caudal fin, the thresher shark is one of the most striking of all sharks. I guess that descriptor could be taken figuratively and literally as it has been shown that the thresher shark uses its tail to swat and stun its prey. Making the media rounds right now is a remarkable series of still photographs taken by marine researcher Scott Sheehan of a thresher shark leaping from the water in Jervis Bay, Australia. Possibly feeding on yellowtail baitfish, the shark leaped from the water and was first thought to be a dolphin. Sheehan readied his camera for a possible second leap and the shark did not disappoint, allowing the researcher to take a rapid series of shots. It is perhaps unusual behavior - or at least a rare occurrence - for a thresher shark to go airborne, but mako sharks have been seen taking large leaps and then, of course, there are the powerful images of great white sharks breaching as they

Hawaiian Reef Sharks: possible competition for food causing massive decline

RTSea: For reef sharks, commercial shark fishing isn't the only thing that threatens their survival. In reef communities near populated islands, an additional threat comes from the taking of fish by local fishermen - fish that often constitute a major portion of the sharks' diets. When local and/or commercial fishermen compete for the same food source as reef shark species, it can be a crippling blow to the shark population. A recent study by Hawaii's Joint Institute for Marine and Atmospheric Research showed a drastic reduction in reef shark populations around populated islands in Hawaii as opposed to more uninhabited islands or pristine reefs. "We found 90-97 percent decline in reef shark abundance: white tip, grey, galapagos and nurse sharks," said Marc Nadon, a researcher with the Institute. The researchers have not been able to determine a more specific cause but look to accidental bycatch (sharks are now more protected, at least from legal commercial shark fishing, due to recent legislation) and overall fishing pressure as contributing factors. "70 percent of reef shark diet is reef fish, so if you remove the food source it would be logical that reef shark would follow the same trend and decline," said Nadon. While the researchers will be doing more studies this fall, their research's concern with competition for food has support based on what has been observed in other island nations. Both Samoa and the Marianas have seen major declines in reef shark populations around populated islands compared to other unspoiled reefs. Source: RTSea

RTSea: For reef sharks, commercial shark fishing isn't the only thing that threatens their survival. In reef communities near populated islands, an additional threat comes from the taking of fish by local fishermen - fish that often constitute a major portion of the sharks' diets. When local and/or commercial fishermen compete for the same food source as reef shark species, it can be a crippling blow to the shark population. A recent study by Hawaii's Joint Institute for Marine and Atmospheric Research showed a drastic reduction in reef shark populations around populated islands in Hawaii as opposed to more uninhabited islands or pristine reefs. "We found 90-97 percent decline in reef shark abundance: white tip, grey, galapagos and nurse sharks," said Marc Nadon, a researcher with the Institute. The researchers have not been able to determine a more specific cause but look to accidental bycatch (sharks are now more protected, at least from legal commercial shark fishing, due to recent legislation) and overall fishing pressure as contributing factors. "70 percent of reef shark diet is reef fish, so if you remove the food source it would be logical that reef shark would follow the same trend and decline," said Nadon. While the researchers will be doing more studies this fall, their research's concern with competition for food has support based on what has been observed in other island nations. Both Samoa and the Marianas have seen major declines in reef shark populations around populated islands compared to other unspoiled reefs. Source: RTSeaBisarbeat: 2,000 Pound white Shark Caught in Mexico

Smartphones and Sharks: video game technology is aiding shark research

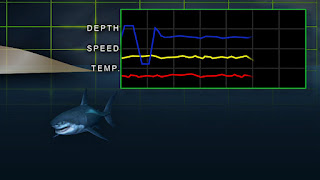

There are a wide range of telemetry tags used in shark research. Some are designed for regional behavior, monitoring a shark's depth, speed, and even internal body temperature. With a limited transmitting range, these tags are ideal for monitoring sharks within a shorter range of less than a mile. Dr. Peter Klimley at UC Davis as become one of the acknowledged masters of the art of regional telemetry tags and I have seen them used extensively with the white sharks at Isla Guadalupe, Baja. However, many sharks species are long-distance travelers and this is where "spot" or satellite tags are preferable. These more sophisticated tags record data for much longer periods of time, periodically downloading their data to satellite networks that surround the planet. Dr. Barbara Block, director of theTOPP Program (Tagging of Pelagic Predators), and Dr. Michael Domeier seen in National Geographic'sExpedition: Great White series, often make use of these types of tags, as do many other researchers for a variety of migratory shark species. With accelerometer tags, scientists like Dr. Whitney can get a glimpse of more than where a shark is, but how it's "feeling" as body movements can be correlated to its respiratory functions and overall metabolism at a given moment. Whitney will be soon starting a research study on blacktip sharks utilizing the accelerometer tags. I can't wait for the video game version to come out for my iPhone. Source: RTSea

There are a wide range of telemetry tags used in shark research. Some are designed for regional behavior, monitoring a shark's depth, speed, and even internal body temperature. With a limited transmitting range, these tags are ideal for monitoring sharks within a shorter range of less than a mile. Dr. Peter Klimley at UC Davis as become one of the acknowledged masters of the art of regional telemetry tags and I have seen them used extensively with the white sharks at Isla Guadalupe, Baja. However, many sharks species are long-distance travelers and this is where "spot" or satellite tags are preferable. These more sophisticated tags record data for much longer periods of time, periodically downloading their data to satellite networks that surround the planet. Dr. Barbara Block, director of theTOPP Program (Tagging of Pelagic Predators), and Dr. Michael Domeier seen in National Geographic'sExpedition: Great White series, often make use of these types of tags, as do many other researchers for a variety of migratory shark species. With accelerometer tags, scientists like Dr. Whitney can get a glimpse of more than where a shark is, but how it's "feeling" as body movements can be correlated to its respiratory functions and overall metabolism at a given moment. Whitney will be soon starting a research study on blacktip sharks utilizing the accelerometer tags. I can't wait for the video game version to come out for my iPhone. Source: RTSea