First Solar Power Plant in Kyrgyzstan Will Save 120,000 Tons of Carbon Emissions Every Year

First projects selected for INL reactor experiments

_15595.jpg) (Image: INL)

(Image: INL)Samsung's 600-Mile-Range Batteries That Charge in 9 Minutes Ready for Production/Sale Next Year

Engineer Powers Entire Home Using 500 Discarded Vapes–Documented in Fascinating Viral Video

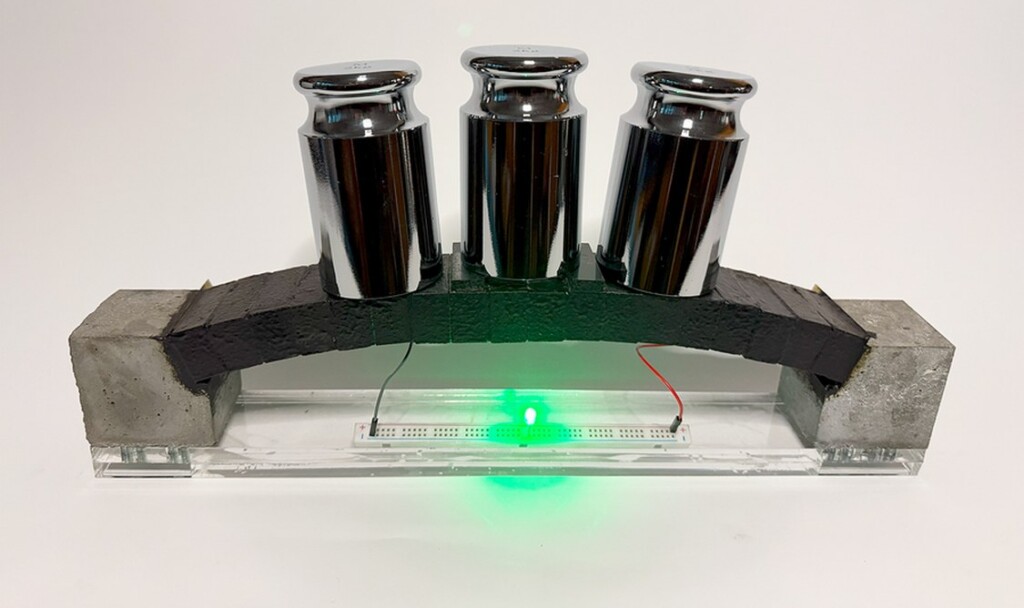

Cement Supercapacitors Could Turn the Concrete Around Us into Massive Energy Storage Systems

credit – MIT Sustainable Concrete Lab

credit – MIT Sustainable Concrete LabIron-Air Batteries Powered by Rust Could Revolutionize Energy Storage By Using Only Iron, Water, and Air

Iron-air batteries for stable power – Credit: Form Energy

Iron-air batteries for stable power – Credit: Form EnergyNew Airship-style Wind Turbine Can Find Gusts at Higher Altitudes for Constant, Cheaper Power

Altaeros’ BAT – credit, Altaeros, via MIT

Altaeros’ BAT – credit, Altaeros, via MITFirst Light Fusion presents novel approach to fusion

_89230.jpg) (Image: First Light Fusion)

(Image: First Light Fusion)GLE completes landmark laser technology demonstration

Resourceful Singapore Finds Perfect Place for 86 MW Solar Farm–its Biggest Reservoir

– credit, courtesy of Sembcorp

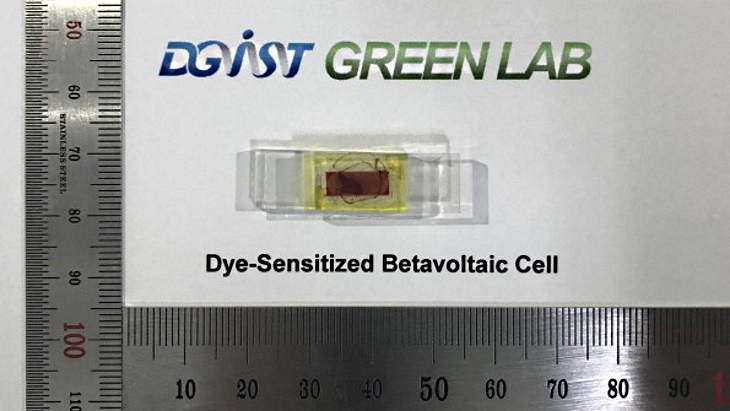

– credit, courtesy of SembcorpJapan, Korea develop prototype nuclear batteries

_11126.jpg) The uranium battery concept (Image: JAEA)

The uranium battery concept (Image: JAEA)

Indian scientists produce green hydrogen by splitting water molecules

New Delhi, (IANS) A team of Indian scientists from the Centre for Nano and Soft Matter Sciences (CeNS), Bengaluru, an autonomous institute of the Department of Science and Technology (DST), have developed a scalable next-generation device that produces green hydrogen by splitting water molecules.

World's First Diamond Battery Could Power Spacecraft and Pacemakers for Thousands of Years

GNN-created image

GNN-created imageElectricity Captured from Falling Rain Conjures the Ultimate Picture of Tropical Sustainability

By Ann Fisher, CC license

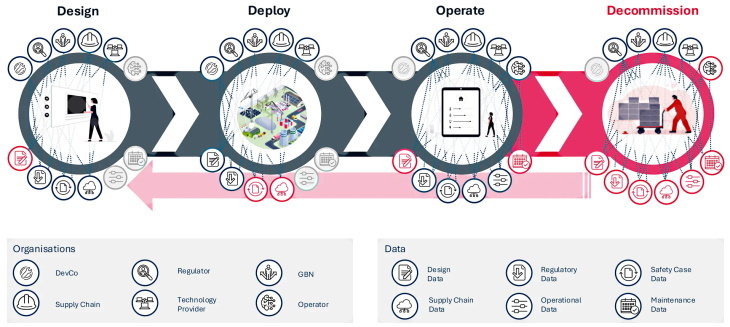

By Ann Fisher, CC licenseViewpoint: Powering the roll-out of advanced nuclear technologies through digital, data and AI

_50521.jpg) Matt Leedham (left) and Derreck Van Gelderen (Image: PA)

Matt Leedham (left) and Derreck Van Gelderen (Image: PA)

A guide: Uranium and the nuclear fuel cycle

Renewables are cheap. So why isn’t your power bill falling?

Power prices are set to go up again even though renewables now account for 40% of the electricity in Australia’s main grid – close to quadruple the clean power we had just 15 years ago. How can that be, given renewables are the cheapest form of newly built power generation?

This is a fair question. As Australia heads for a federal election campaign likely to focus on the rising cost of living, many of us are wondering when, exactly, cheap renewables will bring cheap power.

The simple answer is – not yet. While solar and wind farms produce power at remarkably low cost, they need to be built where it’s sunny or windy. Our existing transmission lines link gas and coal power stations to cities. Connecting renewables to the grid requires expensive new transmission lines, as well as storage for when the wind isn’t blowing or the sun isn’t shining.

Notably, Victoria’s mooted price increase of 0.7% was much lower than other states, which would be as high as 8.9% in parts of New South Wales. This is due to Victoria’s influx of renewables – and good connections to other states. Because Victoria can draw cheap wind from South Australia, hydroelectricity from Tasmania or coal power from New South Wales through a good transmission line network, it has kept wholesale prices the lowest in the national energy market since 2020.

While it was foolish for the Albanese government to promise more renewables would lower power bills by a specific amount, the path we are on is still the right one.

That’s because most of our coal plants are near the end of their life. Breakdowns are more common and reliability is dropping. Building new coal plants would be expensive too. New gas would be pricier still. And the Coalition’s nuclear plan would be both very expensive and arrive sometime in the 2040s, far too late to help.

Renewables are cheap, building a better grid is not

The reason solar is so cheap and wind not too far behind is because there is no fuel. There’s no need to keep pipelines of gas flowing or trainloads of coal arriving to be burned.

But sun and wind are intermittent. During clear sunny days, the National Energy Market can get so much solar that power prices actually turn negative. Similarly, long windy periods can drive down power prices. But when the sun goes down and the wind stops, we still need power.

This is why grid planners want to be able to draw on renewable sources from a wide range of locations. If it’s not windy on land, there will always be wind at sea. To connect these new sources to the grid, though, requires another 10,000 kilometres of high voltage transmission lines to add to our existing 40,000 km. These are expensive and cost blowouts have become common. In some areas, strong objections from rural residents are adding years of delay and extra cost.

So while the cost of generating power from renewables is very low, we have underestimated the cost of getting this power to markets as well as ensuring the power can be “firmed”. Firming is when electricity from variable renewable sources is turned into a commodity able to be turned on or off as needed and is generally done by storing power in pumped hydro schemes or in grid-scale batteries.

In fact, the cost of transmission and firming is broadly offsetting the lower input costs from renewables.

Does this mean the renewable path was wrong?

At both federal and state levels, Labor ministers have made an error in claiming renewables would directly translate to lower power prices.

But consider the counterpoint. Let’s say the Coalition gets in, rips up plans for offshore wind zones and puts the renewable transition on ice. What happens then?

Our coal plants would continue to age, leading to more frequent breakdowns and unreliable power, especially during summer peak demand. Gas is so expensive as to be a last resort. Nuclear would be far in the future. What would be left? Quite likely, expensive retrofits of existing coal plants.

If we stick to the path of the green energy transition, we should expect power price rises to moderate. With more interconnections and transmission lines, we can accommodate more clean power from more sources, reducing the chance of price spikes and adding vital resilience to the grid. If an extreme weather event takes out one transmission line, power can still flow from others.

Storing electricity will be a game-changer

Until now, storing electricity at scale for later use hasn’t been possible. That means grid operators have to constantly match supply and demand. To cope with peak demand, such as a heatwave over summer, we have very expensive gas peaking plants which sit idle nearly all the time.

Solar has only made the challenge harder, as we get floods of solar at peak times and nothing in the evening when we use most of our power. Our coal plants do not deal well with being turned off and on to accommodate solar floods.

The good news is, storage is solving most of these problems. Being able to keep hours or even days of power stored in batteries or in elevated reservoirs at hydroelectric plants gives authorities much more flexibility in how they match supply and demand.

We will never see power “too cheap to meter”, as advocates once said of the nuclear industry. But over time, we should see price rises ease.

For our leaders and energy authorities, this is a tricky time. They must ensure our large-scale transmission line interconnectors actually get built, juggle the flood of renewables, ensure storage comes online, manage the exit of coal plants and try not to affect power prices. Pretty straightforward.![]()

Tony Wood, Program Director, Energy, Grattan Institute

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.