But in our new study my colleagues and I found that the changing climate was driving changes in the polar bear genome, potentially allowing them to more readily adapt to warmer habitats. Provided these polar bears can source enough food and breeding partners, this suggests they may potentially survive these new challenging climates.

We discovered a strong link between rising temperatures in south-east Greenland and changes in polar bear DNA. DNA is the instruction book inside every cell, guiding how an organism grows and develops. In processes called transcription and translation, DNA is copied to generate RNA (molecules that reflect gene activity) and can lead to the production of proteins, and copies of transposons (TEs), also known as “jumping genes”, which are mobile pieces of the genome that can move around and influence how other genes work.

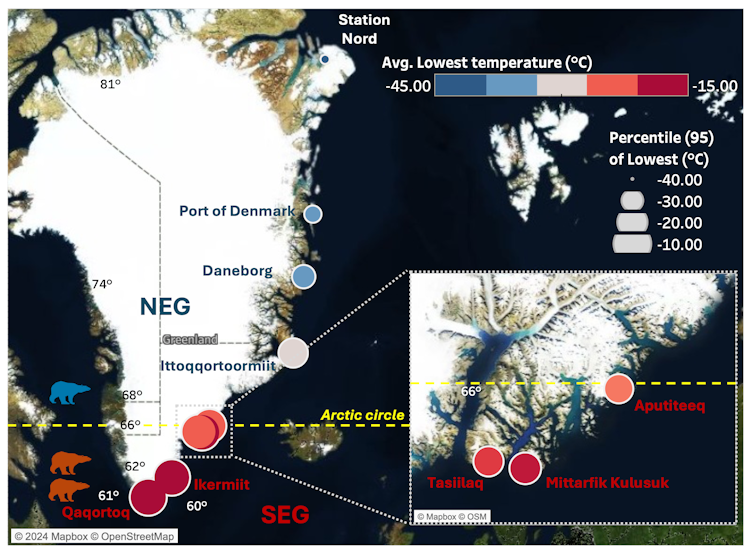

In carrying out our recent research we found that there were big differences in the temperatures observed in the north-east, compared with the south-east regions of Greenland. Our team used publicly available polar bear genetic data from a research group at the University of Washington, US, to support our study. This dataset was generated from blood samples collected from polar bears in both northern and south-eastern Greenland.

Our work built on the Washington University study which discovered that this south-eastern population of Greenland polar bears was genetically different to the north-eastern population. South-east bears had migrated from the north and became isolated and separate approximately 200 years ago, it found.

Researchers from Washington had extracted RNA from polar bear blood samples and sequenced it. We used this RNA sequencing to look at RNA expression — the molecules that act like messengers, showing which genes are active, in relation to the climate. This gave us a detailed picture of gene activity, including the behaviour of TEs. Temperatures in Greenland have been closely monitored and recorded by the Danish Meteorological Institute. So we linked this climate data with the RNA data to explore how environmental changes may be influencing polar bear biology.

Does temperature change anything?

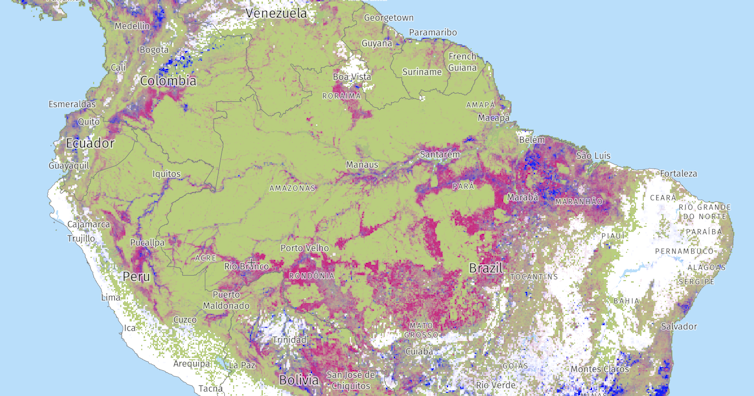

From our analysis we found that temperatures in the north-east of Greenland were colder and less variable, while south-east temperatures fluctuated and were significantly warmer. The figure below shows our data as well as how temperature varies across Greenland, with warmer and more volatile conditions in the south-east. This creates many challenges and changes to the habitats for the polar bears living in these regions.

In the south-east of Greenland, the ice-sheet margin, which is the edge of the ice sheet and spans 80% of Greenland, is rapidly receding, causing vast ice and habitat loss.

The loss of ice is a substantial problem for the polar bears, as this reduces the availability of hunting platforms to catch seals, leading to isolation and food scarcity. The north-east of Greenland is a vast, flat Arctic tundra, while south-east Greenland is covered by forest tundra (the transitional zone between coniferous forest and Arctic tundra). The south-east climate has high levels of rain, wind, and steep coastal mountains.

Temperature across Greenland and bear locations

Author data visualisation using temperature data from the Danish Meteorological Institute. Locations of bears in south-east (red icons) and north-east (blue icons). CC BY-NC-ND

Author data visualisation using temperature data from the Danish Meteorological Institute. Locations of bears in south-east (red icons) and north-east (blue icons). CC BY-NC-NDHow climate is changing polar bear DNA

Over time the DNA sequence can slowly change and evolve, but environmental stress, such as warmer climate, can accelerate this process.

TEs are like puzzle pieces that can rearrange themselves, sometimes helping animals adapt to new environments. In the polar bear genome approximately 38.1% of the genome is made up of TEs. TEs come in many different families and have slightly different behaviours, but in essence they all are mobile fragments that can reinsert randomly anywhere in the genome.

In the human genome, 45% is comprised of TEs and in plants it can be over 70%. There are small protective molecules called piwi-interacting RNAs (piRNAs) that can silence the activity of TEs.

Despite this, when an environmental stress is too strong, these protective piRNAs cannot keep up with the invasive actions of TEs. In our work we found that the warmer south-east climate led to a mass mobilisation from these TEs across the polar bear genome, changing its sequence. We also found that these TE sequences appeared younger and more abundant in the south-east bears, with over 1,500 of them “upregulated”, which suggests recent genetic changes that may help bears adapt to rising temperatures.

Some of these elements overlap with genes linked to stress responses and metabolism, hinting at a possible role in coping with climate change. By studying these jumping genes, we uncovered how the polar bear genome adapts and responds, in the shorter term, to environmental stress and warmer climates.

Our research found that some genes linked to heat-stress, ageing and metabolism are behaving differently in the south-east population of polar bears. This suggests they might be adjusting to their warmer conditions. Additionally, we found active jumping genes in parts of the genome that are involved in areas tied to fat processing – important when food is scarce. This could mean that polar bears in the south-east are slowly adapting to eating the rougher plant-based diets that can be found in the warmer regions. Northern populations of bears eat mainly fatty seals.

Overall, climate change is reshaping polar bear habitats, leading to genetic changes, with south-eastern bears evolving to survive these new terrains and diets. Future research could include other polar bear populations living in challenging climates. Understanding these genetic changes help researchers see how polar bears might survive in a warming world – and which populations are most at risk.

Don’t have time to read about climate change as much as you’d like?

Get a weekly roundup in your inbox instead. Every Wednesday, The Conversation’s environment editor writes Imagine, a short email that goes a little deeper into just one climate issue. Join the 47,000+ readers who’ve subscribed so far.![]()

Alice Godden, Senior Research Associate, School of Biological Sciences, University of East Anglia

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Argo floats are autonomous floats used in an international program to measure ocean conditions like temperature and salinity. Peter Harmsen,

Argo floats are autonomous floats used in an international program to measure ocean conditions like temperature and salinity. Peter Harmsen,

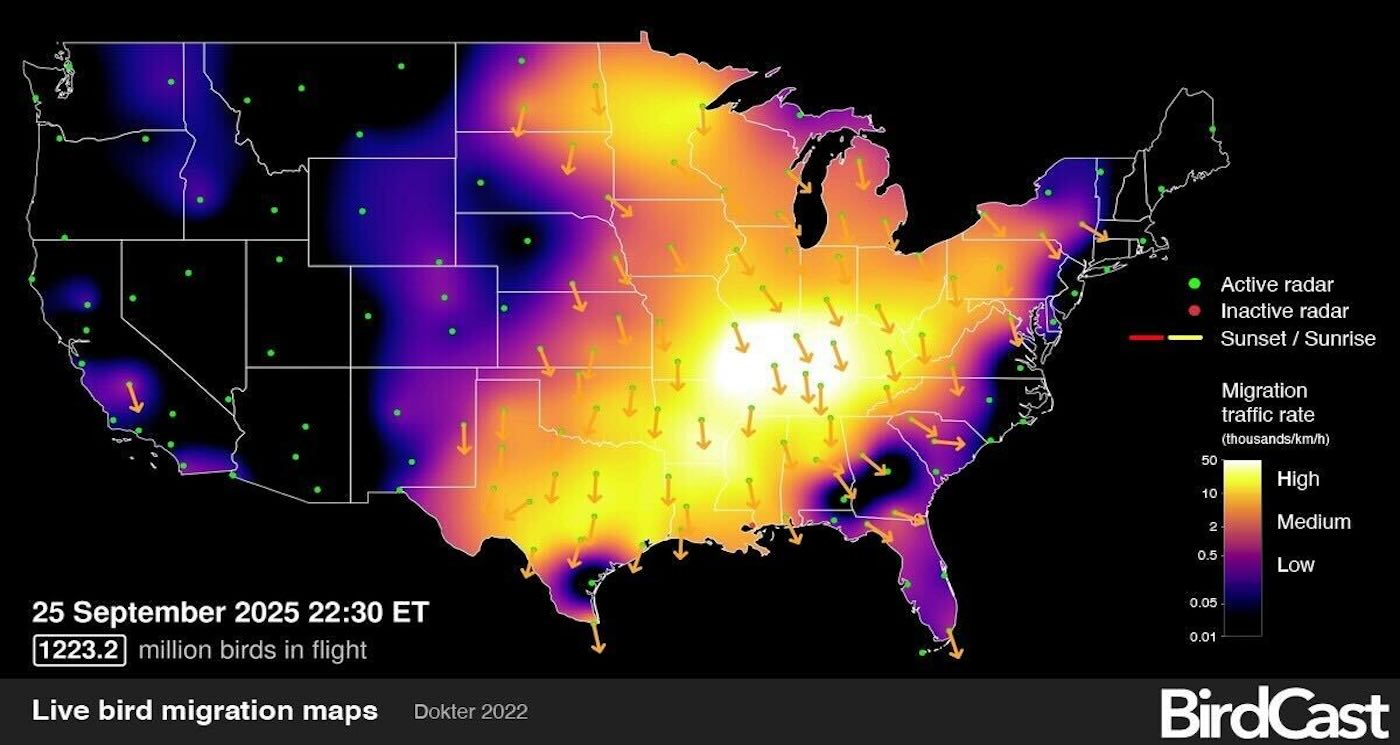

BirdCast

BirdCast (Image: IAEA)

(Image: IAEA)