Facial wound on adult male orangutan – Max Planck Institute of Animal Behavior via SWNS

Facial wound on adult male orangutan – Max Planck Institute of Animal Behavior via SWNS Rakus, 47 days after first treating the wound using the medicinal plant – Max Planck Institute of Animal Behavior via SWNS

Rakus, 47 days after first treating the wound using the medicinal plant – Max Planck Institute of Animal Behavior via SWNS Facial wound on adult male orangutan – Max Planck Institute of Animal Behavior via SWNS

Facial wound on adult male orangutan – Max Planck Institute of Animal Behavior via SWNS Rakus, 47 days after first treating the wound using the medicinal plant – Max Planck Institute of Animal Behavior via SWNS

Rakus, 47 days after first treating the wound using the medicinal plant – Max Planck Institute of Animal Behavior via SWNS

Susan Lawler, La Trobe University: If you had to guess what creature in the world had the largest testes, I doubt you would guess that the prize belonged to a cricket.

The testes of the tuberous bush cricket (Platycleis affinis) are an internal affair, taking up most of the cricket’s abdomen. At nearly 14% of their body weight, they are disproportionately large when compared to other species. Just think, a 100kg human would be walking around with 14kg of testicles, which would be mighty uncomfortable.

Why do these crickets need all that sperm power? It is because their females are highly promiscuous. The male bush crickets do not release more sperm than normal in any given sexual act, but they can be called upon to do it so often they apparently need the reserves. In the world of insects, it is not worth missing an opportunity, and if the females are going to be all available like that, then a cricket needs some world-class balls.

But this is not the only sexual record held by crickets. An Australian species known as scaly crickets (Ornebius aperta) have the most frequent sex of any species in the world. These little guys can do it more than 50 times in a few hours, often with the same female!

Why do they have to keep this up? Because she eats it.

That’s right, cricket sex provides more than the spark for the next generation. Males actually produce a package called a spermatophore, which is sperm wrapped up in a nutritious protein package. When the males insert it into a special opening in the females, sometimes she just bends down to gobble up her yummy post-coital snack.

Australian spiny cricket males respond to this sabotage by releasing only a few sperm per package, between 5 and 225 sperm per copulation, an astonishingly low amount compared to the average (100,000). Yet when researchers measured sperm loads in females, they had up to 20,000 sperm stored away. This means that they had sex up to 200 times to collect that amount.

Of course the females were storing up more than sperm. They also gathered nutrients that will help them develop eggs for the next generation. Other species of crickets manage the situation by offering a courtship gift in the form of food from the dorsal glands that distract the female and give her something to eat during sex.

Some female crickets seek out males in order to get these tasty gifts. A study of 32 different species of bushcrickets showed that the larger the spermatophore, the more likely the females were to actively seek out males. These gifts are costly to produce, so species that produce small spermatophores may mate twice a night, while those with large spermatophores may mate only once or twice in a lifetime.

The final cricket sex record goes to the Mormon cricket, which produces a spermatophore that is 27% of its body weight. That’s a huge investment in wild oats, which is a good description, since most of the package is food. The Mormon crickets are flightless and form swarms similar to locusts. These great walking hordes are often so hungry that cannibalism is common.

Female Mormon crickets will compete for males just so they can get a feed, and the benefit for the male is that some of his sperm may make it to the next generation.

Crickets are not likely to be overly loyal to each other, because research on Spanish field crickets shows that individuals with more mating partners leave more offspring. This applies to both male and female crickets, so it is surprising that males will nevertheless protect a female that they have mated with.

Male crickets will linger near a female they have recently given their sperm to, not to scare away other suitors, but to protect the female from predators. He does this at his own peril, because males that hang about after sex are four times more likely to be eaten. On the other hand, the females are six times less likely to be eaten if he is there to protect her.

Male crickets are not confused about the goal of spermatophore transfer. But female crickets want more than just sperm from their partner. A meal (or several dozen meals) increases the male cricket’s chance of getting lucky.

Maybe they are not so different from people, after all. ![]()

Susan Lawler, Head of Department, Department of Environmental Management & Ecology, La Trobe University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

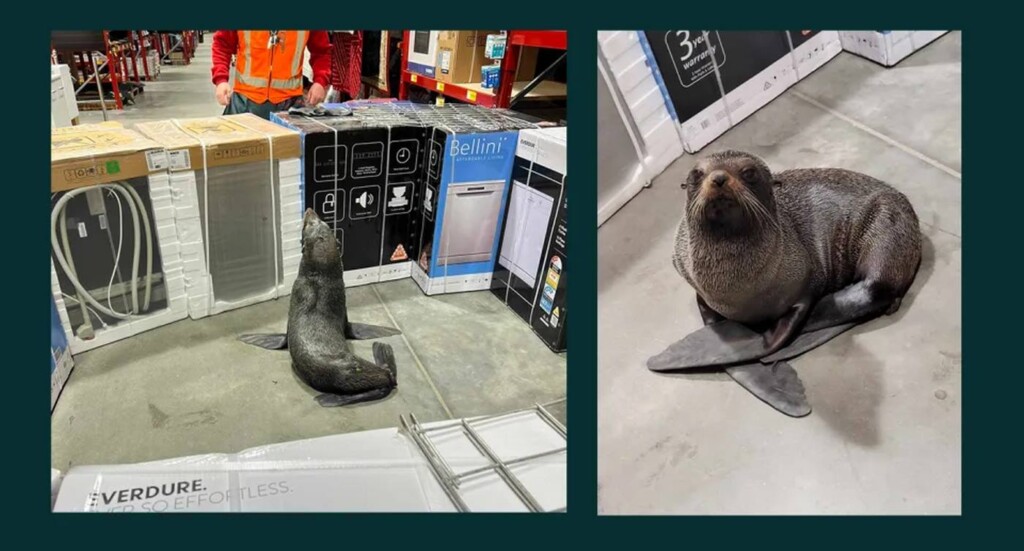

credit – Bunnings, released

credit – Bunnings, released credit – Bunnings, released

credit – Bunnings, released

Photo by Christopher Michel, CC license

Photo by Christopher Michel, CC license Cnemaspis vangoghi – Akshay Khandekar

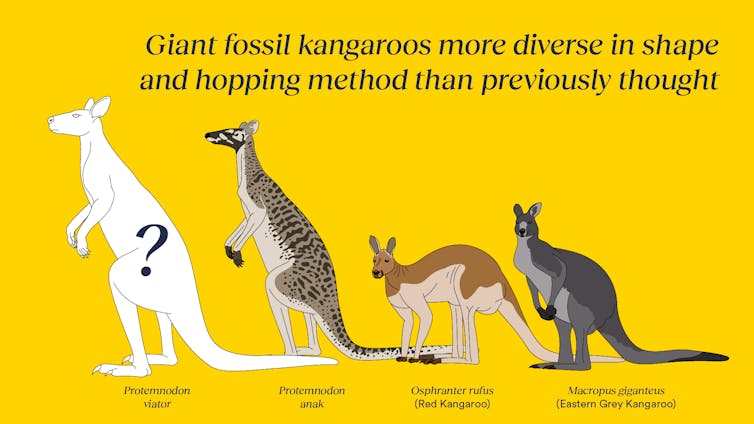

Cnemaspis vangoghi – Akshay Khandekar Artist’s impression of the prehistoric landscape and creatures that Protemnodon would have walked among. Peter Schouten

Isaac A. R. Kerr, Flinders University

Artist’s impression of the prehistoric landscape and creatures that Protemnodon would have walked among. Peter Schouten

Isaac A. R. Kerr, Flinders UniversityFor millions of years, giant animals or megafauna roamed the lands that are now Australia and New Guinea. Many were like much larger versions of modern animals.

There was a four-metre goanna called Megalania (Varanus priscus), for example, which likely ambushed its prey. This beast disappeared by around 40,000 years ago along with almost all the other megafauna aside from remnants such as the red kangaroo and the saltwater crocodile.

Some of the now-vanished kangaroo species were quite massive. The short-faced kangaroo Procoptodon goliah grew as tall as three metres and may have weighed more than 250 kilograms.

There was another genus of extinct kangaroos, Protemnodon, which were more like the grey and red roos we know today, but little has been known about their lives. In a new study, my colleagues and I describe three new species of these vanished marsupials – and shed some light on where they lived and how they got around.

The first species of Protemnodon were described in 1874 by the British naturalist Richard Owen. As was standard at the time, Owen focused chiefly on fossil teeth. Seeing minor differences between teeth from different fragmentary specimens, he described six species of Protemnodon.

However, Owen’s species have not stood the test of time. Our study agrees with only one of his species — Protemnodon anak. The first specimen of P. anak to be described, called the holotype, still resides in the Natural History Museum in London.

Fossils of individual Protemnodon bones are not uncommon, but more complete skeletons are rare. This has hampered palaeontologists’ efforts to study the creatures.

The question of how many species there were, and how to tell them apart, has not been fully answered. This has made it hard to say how the species differed in their size, geographic range, movement and adaptations to their natural environments.

I set out to solve this problem in my PhD project. With fellow PhD student Jacob van Zoelen, I visited the collections of 14 museums in four countries to gather data.

We have now seen just about every piece of Protemnodon that exists above ground, photographing, scanning, measuring, comparing and describing more than 800 specimens collected from all over Australia and New Guinea.

Among all this study, the key to the Protemnodon problem turned out to be buried in the dry bed of Lake Callabonna in northeastern South Australia. Three expeditions to Lake Callabonna from 2013 to 2019 found a megafaunal boneyard: complete skeletons of giant kangaroos, giant wombats, and Genyornis newtoni, a 250kg flightless bird, were scattered among the remains of hundreds of Diprotodon optatum, a rhino-sized marsupial herbivore. This lake likely preserves animals that died while searching for water during prolonged drought.

I accompanied the 2018 trip, which returned with all manner of amazing articulated fossils. These fossils allowed me, then a PhD student in my first year, to begin the process of picking apart the identities of the kangaroos.

Two of Richard Owen’s species, Protemnodon brehus and Protemnodon roechus, were only known from their teeth, which were extremely similar. We unearthed and compared several kangaroos with teeth that could have belonged to either of Owen’s species, but the skeletons didn’t match.

By the international rules of species naming, this meant we had to describe two new species. These are Protemnodon viator from central Australia and Protemnodon mamkurra from southern Australia.

Our study reviews all species of Protemnodon, finding surprising differences. We concluded that there are seven species in the genus, adapted to live in very different environments and even hopping in different ways. This level of variation is unusual within a single genus of kangaroo.

The newly described species Protemnodon viator was bigger than its relative P. anak, and much bigger than the red and Eastern grey kangaroos we know today. Traci Klarenbeek

The newly described species Protemnodon viator was bigger than its relative P. anak, and much bigger than the red and Eastern grey kangaroos we know today. Traci KlarenbeekProtemnodon viator was a large, long-limbed kangaroo that could hop fairly quickly and efficiently. Its name, viator, is Latin for “traveller” or “wayfarer”. Its elongated hind limbs were muscular and narrow, perfect for supporting the kangaroo as it hopped long distances.

Protemnodon viator was well-adapted to its arid central Australian habitat, living in similar areas to the red kangaroos of today. Protemnodon viator was much bigger, however, weighing up to 170 kg, about twice as much as the largest male red kangaroos.

Our study suggests two or three species of Protemnodon may have been mostly quadrupedal, moving something like a quokka or potoroo – bounding on four legs at times, and hopping on two legs at others.

The newly described Protemnodon mamkurra is likely one of these. A large but thick-boned and robust kangaroo, it was probably fairly slow-moving and inefficient. It may have hopped only rarely, perhaps just when startled.

The best fossils of this species come from southeastern South Australia, on the land of the Boandik people. The species name, mamkurra, was chosen by Boandik elders and language experts in the Burrandies Corporation. It means “great kangaroo” in Bunganditj language.

The third of our newly described species is Protemnodon dawsonae, a woodland-dwelling kangaroo from eastern Australia and the probable ancestor of P. viator and P. mamkurra. It is named for kangaroo palaeontologist Lyndall Dawson.

By about 40,000 years ago, despite their many differences, all Protemnodon were extinct on mainland Australia. We don’t yet know why they died out when similar animals such as wallaroos and grey kangaroos survived – but our study may open the door for further Protemnodon research that will find out more about how they lived and why they died.![]()

Isaac A. R. Kerr, Research Assistant at Flinders University Palaeontology Laboratory, Flinders University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Straw-headed bulbul – credit Michael MK Khor CC 2.0. Flickr

Straw-headed bulbul – credit Michael MK Khor CC 2.0. FlickrIn a world first, we heard last week that US surgeons had transplanted a kidney from a gene-edited pig into a living human. News reports said the procedure was a breakthrough in xenotransplantation – when an organ, cells or tissues are transplanted from one species to another.

Champions of xenotransplantation regard it as the solution to organ shortages across the world. In December 2023, 1,445 people in Australia were on the waiting list for donor kidneys. In the United States, more than 89,000 are waiting for kidneys.

One biotech CEO says gene-edited pigs promise “an unlimited supply of transplantable organs”.

Not, everyone, though, is convinced transplanting animal organs into humans is really the answer to organ shortages, or even if it’s right to use organs from other animals this way.

There are two critical barriers to the procedure’s success: organ rejection and the transmission of animal viruses to recipients.

But in the past decade, a new platform and technique known as CRISPR/Cas9 – often shortened to CRISPR – has promised to mitigate these issues.

CRISPR gene editing takes advantage of a system already found in nature. CRISPR’s “genetic scissors” evolved in bacteria and other microbes to help them fend off viruses. Their cellular machinery allows them to integrate and ultimately destroy viral DNA by cutting it.

In 2012, two teams of scientists discovered how to harness this bacterial immune system. This is made up of repeating arrays of DNA and associated proteins, known as “Cas” (CRISPR-associated) proteins.

When they used a particular Cas protein (Cas9) with a “guide RNA” made up of a singular molecule, they found they could program the CRISPR/Cas9 complex to break and repair DNA at precise locations as they desired. The system could even “knock in” new genes at the repair site.

In 2020, the two scientists leading these teams were awarded a Nobel prize for their work.

In the case of the latest xenotransplantation, CRISPR technology was used to edit 69 genes in the donor pig to inactivate viral genes, “humanise” the pig with human genes, and knock out harmful pig genes.

While CRISPR editing has brought new hope to the possibility of xenotransplantation, even recent trials show great caution is still warranted.

In 2022 and 2023, two patients with terminal heart diseases, who were ineligible for traditional heart transplants, were granted regulatory permission to receive a gene-edited pig heart. These pig hearts had ten genome edits to make them more suitable for transplanting into humans. However, both patients died within several weeks of the procedures.

Earlier this month, we heard a team of surgeons in China transplanted a gene-edited pig liver into a clinically dead man (with family consent). The liver functioned well up until the ten-day limit of the trial.

The gene-edited pig kidney was transplanted into a relatively young, living, legally competent and consenting adult.

The total number of gene edits edits made to the donor pig is very high. The researchers report making 69 edits to inactivate viral genes, “humanise” the pig with human genes, and to knockout harmful pig genes.

Clearly, the race to transform these organs into viable products for transplantation is ramping up.

Only a few months ago, CRISPR gene editing made its debut in mainstream medicine.

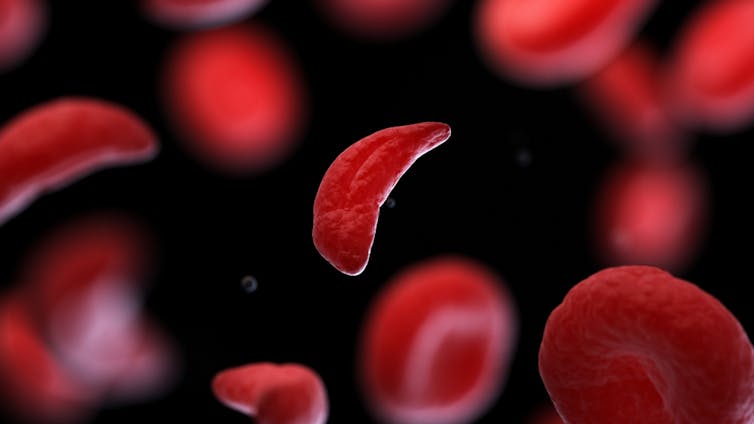

In November, drug regulators in the United Kingdom and US approved the world’s first CRISPR-based genome-editing therapy for human use – a treatment for life-threatening forms of sickle-cell disease.

The treatment, known as Casgevy, uses CRISPR/Cas-9 to edit the patient’s own blood (bone-marrow) stem cells. By disrupting the unhealthy gene that gives red blood cells their “sickle” shape, the aim is to produce red blood cells with a healthy spherical shape.

Although the treatment uses the patient’s own cells, the same underlying principle applies to recent clinical xenotransplants: unsuitable cellular materials may be edited to make them therapeutically beneficial in the patient.

CRISPR technology is aiming to restore diseased red blood cells to their healthy round shape. Sebastian Kaulitzki/Shutterstock

CRISPR technology is aiming to restore diseased red blood cells to their healthy round shape. Sebastian Kaulitzki/ShutterstockMedicine and gene technology regulators are increasingly asked to approve new experimental trials using gene editing and CRISPR.

However, neither xenotransplantation nor the therapeutic applications of this technology lead to changes to the genome that can be inherited.

For this to occur, CRISPR edits would need to be applied to the cells at the earliest stages of their life, such as to early-stage embryonic cells in vitro (in the lab).

In Australia, intentionally creating heritable alterations to the human genome is a criminal offence carrying 15 years’ imprisonment.

No jurisdiction in the world has laws that expressly permits heritable human genome editing. However, some countries lack specific regulations about the procedure.

Even without creating inheritable gene changes, however, xenotransplantation using CRISPR is in its infancy.

For all the promise of the headlines, there is not yet one example of a stable xenotransplantation in a living human lasting beyond seven months.

While authorisation for this recent US transplant has been granted under the so-called “compassionate use” exemption, conventional clinical trials of pig-human xenotransplantation have yet to commence.

But the prospect of such trials would likely require significant improvements in current outcomes to gain regulatory approval in the US or elsewhere.

By the same token, regulatory approval of any “off-the-shelf” xenotransplantation organs, including gene-edited kidneys, would seem some way off.![]()

Christopher Rudge, Law lecturer, University of Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

More than 380 million years ago, a sleek, air-breathing predatory fish patrolled the rivers of central Australia. Today, the sediments of those rivers are outcrops of red sandstone in the remote outback.

Our new paper, published in the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, describes the fossils of this fish, which we have named Harajicadectes zhumini.

Known from at least 17 fossil specimens, Harajicadectes is the first reasonably complete bony fish found from Devonian rocks in central Australia. It has also proven to be a most unusual animal.

The name means “Min Zhu’s Harajica-biter”, after the location where its fossils were found, its presumed predatory habits, and in honour of eminent Chinese palaeontologist Min Zhu, who has made many contributions to early vertebrate research.

Harajicadectes was a fish in the Tetrapodomorpha group. This group had strongly built paired fins and usually only a single pair of external nostrils.

Tetrapodomorph fish from the Devonian period (359–419 million years ago) have long been of great interest to science. They include the forerunners of modern tetrapods – animals with backbones and limbs such as amphibians, reptiles, birds and mammals.

For example, recent fossil discoveries show fingers and toes arose in this group.

Devonian fossil sites in northwestern and eastern Australia have produced many spectacular discoveries of early tetrapodomorphs.

But until our discovery, the poorly sampled interior of the continent had only offered tantalising fossil fragments.

Our species description is the culmination of 50 years of tireless exploration and research.

Palaeontologist Gavin Young from the Australian National University made the initial discoveries in 1973 while exploring the Middle-Late Devonian Harajica Sandstone on Luritja/Arrernte country, more than 150 kilometres west of Alice Springs (Mparntwe).

Packed within red sandstone blocks on a remote hilltop were hundreds of fossil fishes. The vast majority of them were small Bothriolepis – a type of widespread prehistoric fish known as a placoderm, covered in box-like armour.

Scattered among them were fragments of other fishes. These included a lungfish known as Harajicadipterus youngi, named in honour of Gavin Young and his years of work on material from Harajica.

There were also spines from acanthodians (small, vaguely shark-like fish), the plates of phyllolepids (extremely flat placoderms) and, most intriguingly, jaw fragments of a previously unknown tetrapodomorph.

The moment of discovery when we found a complete fossil of Harajicadectes in 2016. Flinders University palaeontologists John Long (centre), Brian Choo (right) and Alice Clement (left) with ANU palaeontologist Gavin Young (top left). Author provided

The moment of discovery when we found a complete fossil of Harajicadectes in 2016. Flinders University palaeontologists John Long (centre), Brian Choo (right) and Alice Clement (left) with ANU palaeontologist Gavin Young (top left). Author providedMany more partial specimens of this Harajica tetrapodomorph were collected in 1991, including some by the late palaeontologist Alex Ritchie.

There were early attempts at figuring out the species, but this proved troublesome. Then, our Flinders University expedition to the site in 2016 yielded the first almost complete fossil of this animal.

This beautiful specimen demonstrated that all the isolated bits and pieces collected over the years belonged to a single new type of fish. It is now in the collections of the Museum and Art Gallery of the Northern Territory, serving as the type specimen of Harajicadectes.

Up to 40 centimetres long, Harajicadectes is the biggest fish found in the Harajica rocks. Likely the top predator of those ancient rivers, its big mouth was lined with closely-packed sharp teeth alongside larger, widely spaced triangular fangs.

It seems to have combined anatomical traits from different tetrapodomorph lineages via convergent evolution (when different creatures evolve similar features independently). An example of this are the patterns of bones in its skull and scales. Exactly where it sits among its closest relatives is difficult to resolve.

Artist’s reconstruction of Harajicadectes menacing a pair of armoured Bothriolepis. Artist: Brian Choo

Artist’s reconstruction of Harajicadectes menacing a pair of armoured Bothriolepis. Artist: Brian ChooThe most striking and perhaps most important features are the two huge openings on the top of the skull called spiracles. These typically only appear as minute slits in most early bony fishes.

Similar giant spiracles also appear in Gogonasus, a marine tetrapodomorph from the famous Late Devonian Gogo Formation of Western Australia. (It doesn’t appear to be an immediate relative of Harajicadectes.)

They are also seen in the unrelated Pickeringius, an early ray-finned fish that was also at Gogo.

Other Devonian animals that sported such spiracles were the famous elpistostegalians – freshwater tetrapodomorphs from the Northern Hemisphere such as Elpistostege and Tiktaalik.

These animals were extremely close to the ancestry of limbed vertebrates. So, enlarged spiracles seem to have arisen independently in at least four separate lineages of Devonian fishes.

The only living fishes with similar structures are bichirs, African ray-finned fishes that live in shallow floodplains and estuaries. It was recently confirmed they draw surface air through their spiracles to aid survival in oxygen-poor waters.

That these structures appeared roughly simultaneously in four Devonian lineages provides a fossil “signal” for scientists attempting to reconstruct atmospheric conditions in the distant past.

It could help us uncover the evolution of air breathing in backboned animals.![]()

Brian Choo, Postdoctoral fellow in vertebrate palaeontology, Flinders University; Alice Clement, Research Associate in the College of Science and Engineering, Flinders University, and John Long, Strategic Professor in Palaeontology, Flinders University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Shutterstock

Bryan G. Fry, The University of Queensland

Shutterstock

Bryan G. Fry, The University of QueenslandThe green anaconda has long been considered one of the Amazon’s most formidable and mysterious animals. Our new research upends scientific understanding of this magnificent creature, revealing it is actually two genetically different species. The surprising finding opens a new chapter in conservation of this top jungle predator.

Green anacondas are the world’s heaviest snakes, and among the longest. Predominantly found in rivers and wetlands in South America, they are renowned for their lightning speed and ability to asphyxiate huge prey then swallow them whole.

My colleagues and I were shocked to discover significant genetic differences between the two anaconda species. Given the reptile is such a large vertebrate, it’s remarkable this difference has slipped under the radar until now.

Conservation strategies for green anacondas must now be reassessed, to help each unique species cope with threats such as climate change, habitat degradation and pollution. The findings also show the urgent need to better understand the diversity of Earth’s animal and plant species before it’s too late.

Scientists discovered a new snake species known as the northern green anaconda. Bryan Fry

Scientists discovered a new snake species known as the northern green anaconda. Bryan FryHistorically, four anaconda species have been recognised, including green anacondas (also known as giant anacondas).

Green anacondas are true behemoths of the reptile world. The largest females can grow to more than seven metres long and weigh more than 250 kilograms.

The snakes are well-adapted to a life lived mostly in water. Their nostrils and eyes are on top of their head, so they can see and breathe while the rest of their body is submerged. Anacondas are olive-coloured with large black spots, enabling them to blend in with their surroundings.

The snakes inhabit the lush, intricate waterways of South America’s Amazon and Orinoco basins. They are known for their stealth, patience and surprising agility. The buoyancy of the water supports the animal’s substantial bulk and enables it to move easily and leap out to ambush prey as large as capybaras (giant rodents), caimans (reptiles from the alligator family) and deer.

Green anacondas are not venomous. Instead they take down prey using their large, flexible jaws then crush it with their strong bodies, before swallowing it.

As apex predators, green anacondas are vital to maintaining balance in their ecosystems. This role extends beyond their hunting. Their very presence alters the behaviour of a wide range of other species, influencing where and how they forage, breed and migrate.

Anacondas are highly sensitive to environmental change. Healthy anaconda populations indicate healthy, vibrant ecosystems, with ample food resources and clean water. Declining anaconda numbers may be harbingers of environmental distress. So knowing which anaconda species exist, and monitoring their numbers, is crucial.

To date, there has been little research into genetic differences between anaconda species. Our research aimed to close that knowledge gap.

Green anaconda have large, flexible jaws. Pictured: a green anaconda eating a deer. JESUS RIVAS

Green anaconda have large, flexible jaws. Pictured: a green anaconda eating a deer. JESUS RIVASWe studied representative samples from all anaconda species throughout their distribution, across nine countries.

Our project spanned almost 20 years. Crucial pieces of the puzzle came from samples we collected on a 2022 expedition to the Bameno region of Baihuaeri Waorani Territory in the Ecuadorian Amazon. We took this trip at the invitation of, and in collaboration with, Waorani leader Penti Baihua. Actor Will Smith also joined the expedition, as part of a series he is filming for National Geographic.

We surveyed anacondas from various locations throughout their ranges in South America. Conditions were difficult. We paddled up muddy rivers and slogged through swamps. The heat was relentless and swarms of insects were omnipresent.

We collected data such as habitat type and location, and rainfall patterns. We also collected tissue and/or blood from each specimen and analysed them back in the lab. This revealed the green anaconda, formerly believed to be a single species, is actually two genetically distinct species.

The first is the known species, Eunectes murinus, which lives in Perú, Bolivia, French Guiana and Brazil. We have given it the common name “southern green anaconda”. The second, newly identified species is Eunectes akayima or “northern green anaconda”, which is found in Ecuador, Colombia, Venezuela, Trinidad, Guyana, Suriname and French Guiana.

We also identified the period in time where the green anaconda diverged into two species: almost 10 million years ago.

The two species of green anaconda look almost identical, and no obvious geographical barrier exists to separate them. But their level of genetic divergence – 5.5% – is staggering. By comparison, the genetic difference between humans and apes is about 2%.

The two green anaconda species live much of their lives in water. Shutterstock

The two green anaconda species live much of their lives in water. ShutterstockOur research has peeled back a layer of the mystery surrounding green anacondas. This discovery has significant implications for the conservation of these species – particularly for the newly identified northern green anaconda.

Until now, the two species have been managed as a single entity. But each may have different ecological niches and ranges, and face different threats.

Tailored conservation strategies must be devised to safeguard the future of both species. This may include new legal protections and initiatives to protect habitat. It may also involve measures to mitigate the harm caused by climate change, deforestation and pollution — such as devastating effects of oil spills on aquatic habitats.

Our research is also a reminder of the complexities involved in biodiversity conservation. When species go unrecognised, they can slip through the cracks of conservation programs. By incorporating genetic taxonomy into conservation planning, we can better preserve Earth’s intricate web of life – both the species we know today, and those yet to be discovered.![]()

Bryan G. Fry, Professor of Toxicology, School of the Environment, The University of Queensland

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Shutterstock Bradley Smith, CQUniversity Australia and Mia Cobb, The University of MelbourneFor many of us, dogs are our best friends. But have you wondered what would happen to your dog if we suddenly disappeared? Can domestic dogs make do without people?

Shutterstock Bradley Smith, CQUniversity Australia and Mia Cobb, The University of MelbourneFor many of us, dogs are our best friends. But have you wondered what would happen to your dog if we suddenly disappeared? Can domestic dogs make do without people?

At least 80% of the world’s one billion or so dogs actually live independent, free-ranging lives – and they offer some clues. Who would our dogs be if we weren’t around to influence and care for them?

Dogs hold the title of the most successful domesticated species on Earth. For millennia they have evolved under our watchful eye. More recently, selective breeding has led to people-driven diversity, resulting in unique breeds ranging from the towering Great Dane to the tiny Chihuahua.

Humanity’s quest for the perfect canine companion has resulted in more than 400 modern dog breeds with unique blends of physical and behavioural traits. Initially, dogs were bred primarily for functional roles that benefited us, such as herding, hunting and guarding. This practice only emerged prominently over the past 200 years.

Some experts suggest companionship is just another type of work humans selected dogs for, while placing a greater emphasis on looks. Breeders play a crucial role in this, making deliberate choices about which traits are desirable, thereby influencing the future direction of breeds.

We know certain features that appeal to people have serious impacts on health and happiness. For instance, flat-faced dogs struggle with breathing due to constricted nasal passages and shortened airways. This “air hunger” has been likened to experiencing an asthma attack. These dogs are also prone to higher rates of skin, eye and dental problems compared with dogs with longer muzzles.

Flat-faced dogs such as pugs and bulldogs often aren’t comfortable in the bodies we’ve bred them for. Shutterstock

Flat-faced dogs such as pugs and bulldogs often aren’t comfortable in the bodies we’ve bred them for. ShutterstockMany modern dogs depend on human medical intervention to reproduce. For instance, French Bulldogs and Chihuahuas frequently require a caesarean section to give birth, as the puppies’ heads are very large compared with the mother’s pelvic width. This reliance on surgery to breed highlights the profound impact intensive selective breeding has on dogs.

And while domestic dogs can benefit from being part of human families, some live highly isolated and controlled lives in which they have little agency to make choices – a factor that’s important to their happiness.

Now imagine a world where dogs are free from the guiding hand of human selection and care. The immediate impact would be stark. Breeds that are heavily dependent on us for basic needs such as food, shelter and healthcare wouldn’t do well. They would struggle to adapt, and many would succumb to the harsh realities of a life without human support.

That said, this would probably impact fewer than 20% of all dogs (roughly the percentage living in our homes). Most of the world’s dogs are free-ranging and prevalent across Europe, Africa and Asia.

Many dogs live independently around people, like these dogs seen on the street in India. Shutterstock

Many dogs live independently around people, like these dogs seen on the street in India. ShutterstockBut while these dogs aren’t domesticated in a traditional sense, they still coexist with humans. As such, their survival depends almost exclusively on human-made resources such as garbage dumps and food handouts. Without people, natural selection would swiftly come into play. Dogs that lack essential survival traits such as adaptability, hunting skills, disease resistance, parental instincts and sociability would gradually decline.

Dogs that are either extremely large or extremely small would also be at a disadvantage, because a dog’s size will impact its caloric needs, body temperature regulation across environments, and susceptibility to predators.

Limited behavioural strategies, such as being too shy to explore new areas, would also be detrimental. And although sterilised dogs might have advantageous survival traits, they would be unable to pass their genes on to future generations.

Rearing puppies without human support happens successfully around the world. Shutterstock

Rearing puppies without human support happens successfully around the world. ShutterstockUltimately, a different type of dog would emerge, shaped by health and behavioural success rather than human desires.

Dogs don’t select mates based on breed, and will readily mate with others that look very different to them when given the opportunity. Over time, distinct dog breeds would fade and unrestricted mating would lead to a uniform “village dog” appearance, similar to “camp dogs” in remote Indigenous Australian communities and dogs seen in South-East Asia.

These dogs typically have a medium size, balanced build, short coats in various colours, and upright ears and tails. However, regional variations such as a shaggier coat could arise due to factors such as climate.

In the long term, dogs would return to a wild canid lifestyle. These “re-wilded” dogs would likely adopt social and dietary behaviours similar to those of their current wild counterparts, such as Australia’s dingoes. This might include living in small family units within defined territories, reverting to an annual breeding season, engaging in social hunting, and attentive parental care (especially from dads).

This transition would be more feasible for certain breeds, particularly herding types and those already living independently in the wild or as village dogs.

In their book A Dog’s World, Jessica Pierce and Marc Bekoff explore the idea of “doomsday prepping” our dogs for a future without people. They encourage us to give our dogs more agency, and consequently more happiness. This could be as simple as letting them pick which direction to walk in, or letting them take their time when sniffing a tree.

As we reflect on a possible future without dogs, an important question arises: are our actions towards dogs sustainable, in their best interests, and true to their nature? Or are they more aligned with our own desires?

By considering how dogs might live without us, perhaps we can find ways to improve their lives with us.![]()

Providing a good life for dogs requires thinking about their mental well-being, health and environment. Shutterstock

Providing a good life for dogs requires thinking about their mental well-being, health and environment. ShutterstockBradley Smith, Senior Lecturer in Psychology, CQUniversity Australia and Mia Cobb, Research Fellow, Animal Welfare Science Centre, The University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Shutterstock Brandon Michael Sideleau, Charles Darwin University

Shutterstock Brandon Michael Sideleau, Charles Darwin University

On January 4 this year, a three-metre saltwater crocodile heaved itself out of the water and up the beach. Nothing unusual about that – except this croc was on Legian Beach, one of Bali’s most popular spots. The emaciated reptile later died.

Only four months later, a large crocodile killed a man who was spearfishing with friends in Lombok’s Awang Bay, about 100 kilometres east of Bali. Authorities caught it and transferred it to captivity.

You might not associate crocodiles with Bali. But the saltwater crocodile once roamed most of Indonesia’s waters, and attacks are still common in some regions. I have been collecting records of crocodilian attacks since 2010, as the creator of the worldwide database CrocAttack. What’s new is that they’re beginning to return to areas where they were wiped out.

Does this mean tourists and residents should be wary? It’s unlikely these islands can host anywhere near the same population densities as the wide, fish-filled rivers of Australia’s tropical north. And in Bali, it’s unlikely we’ll see any crocodile recovery because of the importance of beaches to tourism and a high human population.

This 4.6-metre saltwater crocodile was captured in Lombok after the fatal attack in May. Bali Reptile Rescue, CC BY-ND

This 4.6-metre saltwater crocodile was captured in Lombok after the fatal attack in May. Bali Reptile Rescue, CC BY-NDSaltwater crocodiles (Crocodylus porosus) are also known as estuarine crocodiles, as they prefer to live in mangrove-lined rivers. They’re the largest living reptile, reaching up to seven metres in length – far larger than Indonesia’s famous Komodo dragon, which tops out at three metres.

Historically, crocodiles lived throughout the Indonesian archipelago. We have records of attacks on humans in Bali from the early 20th century and across much of Java until the 1950s. Even Indonesia’s capital, Jakarta, had crocodiles resident in many rivers running through the city.

Crocodiles in Bali and Lombok were killed off by the mid-20th century, and later across Java. But they survived in more remote parts of the island nation.

Salties are now being regularly sighted in Indonesia’s densely populated island of Java, including in seas off Jakarta. At least 70 people are killed by crocs every year across the archipelago, with the highest numbers of attacks being reported from the Bangka-Belitung islands off Sumatra and the provinces of East Kalimantan, East Nusa Tenggara, and Riau.

These incidents means numbers are increasing. But recovery may not be as significant as it seems.

On many Indonesian islands, there’s very limited mangrove habitat suitable for crocodiles, and many creeks and rivers may be naturally too small for more than a small number of them. Even a small population recovery could quickly fill up the croc capacity of estuaries and creeks. These crocodiles are the most territorial of all crocodilians. Dominant males push out smaller male crocodiles, who set out in search of new habitat.

To date, Indonesia’s crocodile surveys reveal mostly small and low-density populations. But even the arrival of a single crocodile into human territory can spark conflict – and threaten the conservation of the species.

Worldwide, saltwater crocodiles are listed as a species of least concern on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, thanks to their full population recovery in parts of northern Australia after hunting was banned in the early 1970s. But in Cambodia, Thailand, and Vietnam the species is extinct.

Even in sparsely populated northern Australia, there’s still conflict between humans and crocs, though this conflict is comparatively rare. In Indonesia, the problem is compounded by a massive human population which puts pressure on crocodile habitat.

You might look at a map and think crocodiles moving back into Bali are coming from Australia. But there is currently no evidence of significant crocodile movement between Australia and Indonesia. It would be a brave crocodile to swim more than 1,000 kilometres from Australia to Bali.

What we are likely witnessing is a crocodile exodus from nearby areas, though we would need to do genetic analysis to prove it. That’s because the surviving croc population centres are much closer than Australia. For Bali and Lombok, crocodiles are likely migrating from the islands to the east, such as Flores, Lembata, Sumba and Timor.

The most likely source of Java’s crocodile arrivals is southern Sumatra, which is less than 30km from Java at its nearest. This area has long been prone to crocodile attacks.

Earlier this month, a relatively large crocodile was photographed basking on a large fish trap in West Lombok, less than 50km from the tourist hotspot of the Gili Islands.

The spike in sightings and attacks suggests we’re going to have to find ways of living alongside these reptiles. The coastal waters and estuaries of Lombok and western Java are now likely home to a small resident population.

What can be done to prevent attacks? First, people have to know that crocs are back. Increasing crocodile awareness and caution is vital to save lives.

Some researchers believe attacks on us and our livestock get more likely if mangroves have been destroyed or fishing grounds fished out. Protecting crocodile habitat and prey species can both secure the future of the species and cut the risk of attacks.

Does it mean you should cancel your next Bali trip? No. While restoration efforts have brought back tracts of mangroves along some coastlines in Bali, the sheer popularity of the island means it’s unlikely any crocodile population will ever be reestablished there.

But we could well see crocodiles slowly return to less populated parts of Java and Lombok. While that may fill us with anxiety, they’re a vital part of the ecosystem. Crocodiles are meant to be there. ![]()

Brandon Michael Sideleau, PhD student studying human-saltwater crocodile conflict, Charles Darwin University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.