You pull on your rain jacket, step out into the storm, and within half an hour your undershirt is soaked. The jacket you purchased as “waterproof” seems to have stopped working, and all the marketing claims feel a bit suspect.

In reality, the jacket probably hasn’t failed overnight: a mix of how it’s built, the exact level of water protection it offers, and years of sweat, skin oil and dirt have all played a part.

But there are a few simple ways you can care for your rain jacket to ensure you stay dry, even when it’s pouring.

The science behind rain jackets

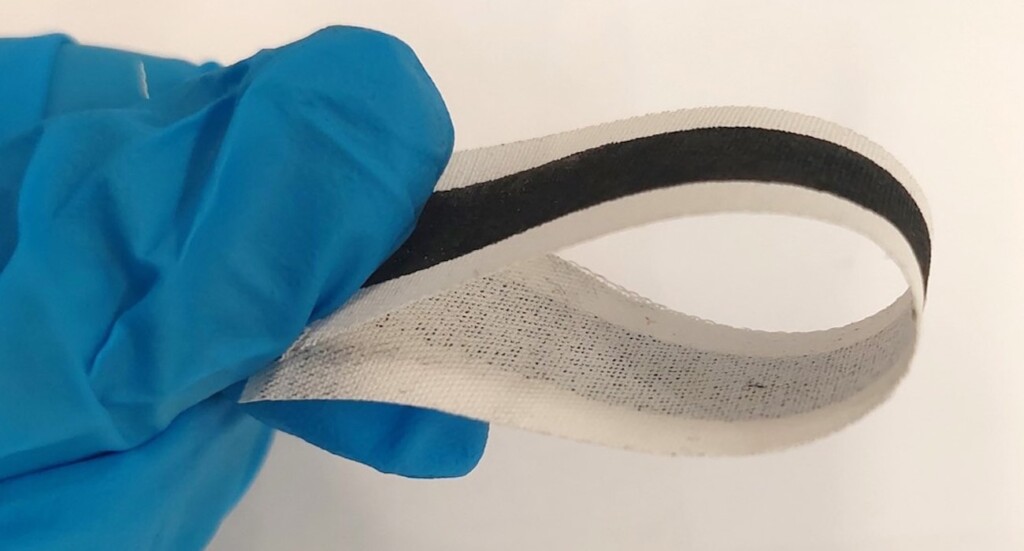

Most proper rain jackets are built around a waterproof “membrane” sandwiched inside the fabric. Gore-Tex is the most popular technology used which includes a very thin layer of chemicals known as PTFE (polytetrafluoroethylene) or expanded PTFE (ePTFE) which are full of microscopic pores.

Those pores are much smaller than liquid water droplets. But they’re big enough for individual water vapour molecules, so rain on the outside can’t push through, but sweat vapour from your body can escape outwards.

Other fabrics use solid, non-porous membranes made from polyurethane or polyester that move water vapour by absorbing it and passing it through the material molecule by molecule rather than via tiny holes. This can make them a bit more tolerant of dirt.

The outer fabric is sometimes treated with a very thin chemical finish that makes water roll off the surface instead of soaking into the fibres – a bit like wax on a car. This finish is known as “Durable Water Repellent” and helps to reduce saturation of water in the exterior of the jacket.

In the past, many of these chemical finishes used “forever chemicals” (PFAS) that repelled both water and oil, but persist in the environment and build up in wildlife and people.

Because of this, brands and regulators have started using alternatives based on silicones or hydrocarbons. These still repel water but are generally less hazardous.

It’s also useful to understand the words you see on labels.

A waterproof jacket is built to stop rain coming through, even in heavy or prolonged downpours, and usually has a membrane, a chemical finish plus fully taped seams.

“Water resistant” means the fabric slows water down and copes with light showers but will eventually let water through. It often relies on a tight weave and a chemical finish but no true membrane.

“Water repellent” just describes that beading effect from the chemical finish. It can apply to both waterproof and non-waterproof fabrics.

Some brands also say rainproof or weatherproof as a friendlier way of saying “pretty much waterproof”, but there’s rarely a separate test behind that word.

Why do rain jackets degrade over time?

When you realise your jacket isn’t waterproof anymore, the first thing that has usually gone wrong isn’t the membrane. It’s the chemical finish on the outside.

That ultra thin surface layer gets scuffed by backpack straps and seat belts, baked by sun, and contaminated by mud, smoke and city grime.

These coatings can gradually lose their water repellent properties through abrasion and washing if harsh detergents and washing cycles are used, and bits of them are shed into the environment over time.

Body oils, sunscreen and insect repellent also play a role, as they build up in the fabric over time. Outdoor gear care guides and lab work on waterproof fabrics both point out that these oily contaminants can damage the chemical finish and clog the pores of the membrane, making it harder both for rain to be repelled and for sweat vapour to escape.

Over many years, slow physical ageing also takes a toll. Constant flexing can cause a membrane to thin or develop tiny cracks and the finish to deteriorate. Seam tapes can also start to peel away, especially on shoulders where backpack straps press.

How to keep a jacket waterproof

The single best thing you can do for both your comfort and the planet is to keep a good jacket working for as long as possible, because making new technical fabrics has a significant environmental footprint.

Gentle washing will help extend the life of your rain jacket, as it removes the build up of contamination such as dirt and body oils. Brands and care guides recommend closing zips and Velcro, then washing on a gentle cycle with a cleaner designed for waterproof fabrics or a very mild soap, avoiding normal detergents and softeners that leave residues.

Depending on the type of chemical finish, this coat can be re-applied through spray-on or wash-in products found commercially. Some finishes can be re-activated by exposure to low heat (low dryer heat or low ironing heat). Heat makes the water-repelling molecules stand back up after they have been “flattened” by use and contamination.

Although the above will help you to keep your jacket waterproof, it is best to follow the care instructions given by the manufacturer as they change according to the type of composition of the fabric.

In any case, it is important to avoid leaving the jacket wet and scrunched up for weeks, and be mindful of heavy sunscreens and repellents.![]()

Carolina Quintero Rodriguez, Senior Lecturer and Program Manager, Bachelor of Fashion (Enterprise) program, RMIT University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

_86671.jpg)