ICRISAT develops portable technology for testing crops' nutrition level

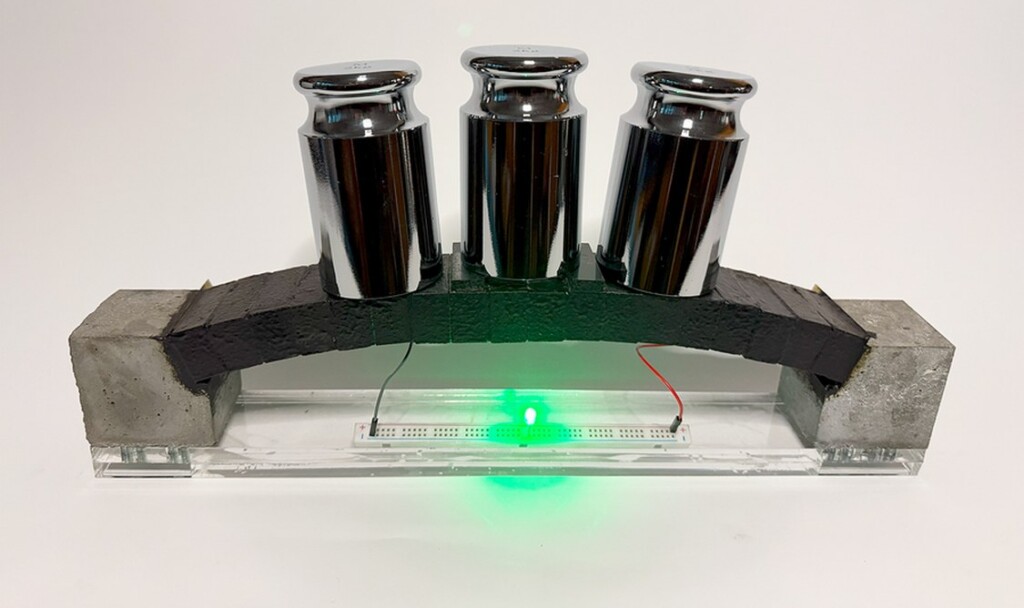

Cement Supercapacitors Could Turn the Concrete Around Us into Massive Energy Storage Systems

credit – MIT Sustainable Concrete Lab

credit – MIT Sustainable Concrete LabTinyML: The Small Technology Tackling the Biggest Climate Challenge

Nanotechnology breakthrough may boost treatment for aggressive breast cancer: Study

Qualcomm drives digital future with AI, 6G and 'Make in India' initiatives

IANS Photo

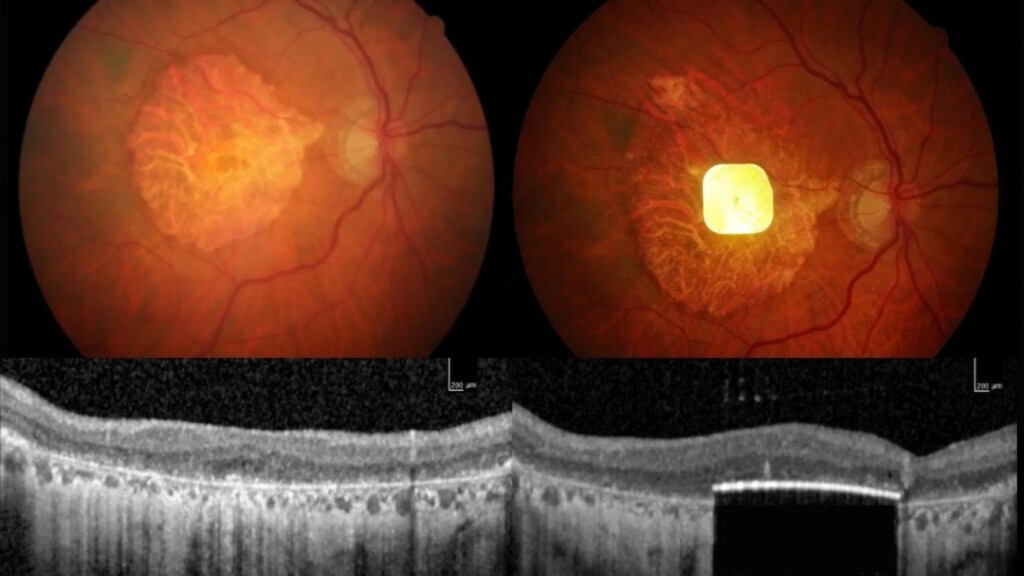

IANS PhotoA Combination Implant and Augmented Reality Glasses Restores Reading Vision to Blind Eyes

Study participant Sheila Irvine training with the device – credit Moorfields Eye Hospital

Study participant Sheila Irvine training with the device – credit Moorfields Eye Hospital Scans of the implant in a patient’s eye – credit Science Corporation

Scans of the implant in a patient’s eye – credit Science CorporationFirst Light Fusion presents novel approach to fusion

_89230.jpg) (Image: First Light Fusion)

(Image: First Light Fusion)GLE completes landmark laser technology demonstration

Scientists Regrow Retina Cells to Tackle Leading Cause of Blindness Using Nanotechnology

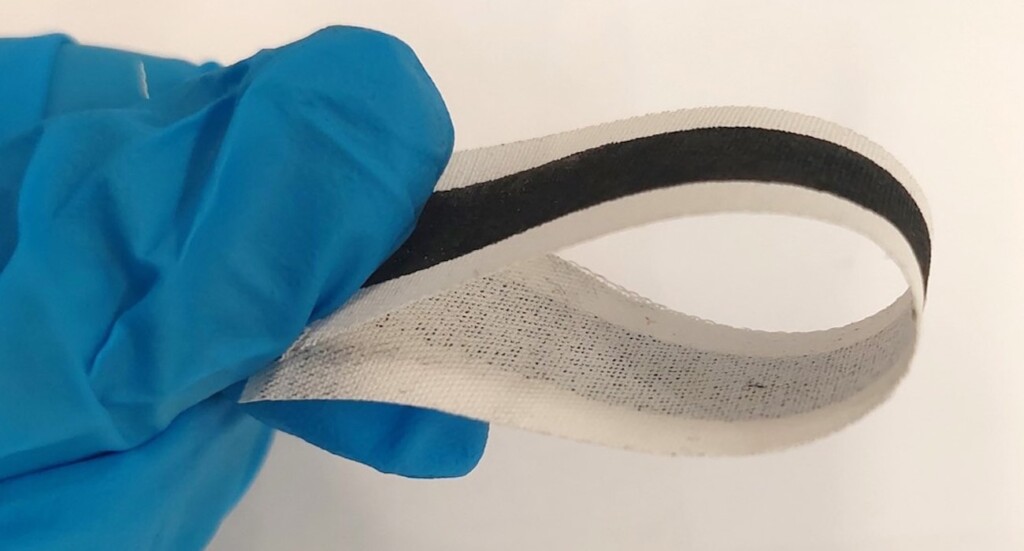

Scientists Develop Biodegradable Smart Textile–A Big Leap Forward for Eco-Friendly Wearable Technology

Flexible inkjet printed E-textile – Credit: Marzia Dulal

Flexible inkjet printed E-textile – Credit: Marzia Dulal Gloves with e-textile sensors monitoring heart rate – Credit: Marzia Dulal

Gloves with e-textile sensors monitoring heart rate – Credit: Marzia Dulal Four strips in a variety of decomposed states, during four months of decomposition – Credit: Marzia Dulal

Four strips in a variety of decomposed states, during four months of decomposition – Credit: Marzia DulalWorldwide spending on AI is expected to be nearly $1.5 trillion in 2025: Report

IANS Photo

IANS PhotoBlue, green, brown, or something in between – the science of eye colour explained

You’re introduced to someone and your attention catches on their eyes. They might be a rich, earthy brown, a pale blue, or the rare green that shifts with every flicker of light. Eyes have a way of holding us, of sparking recognition or curiosity before a single word is spoken. They are often the first thing we notice about someone, and sometimes the feature we remember most.

Across the world, human eyes span a wide palette. Brown is by far the most common shade, especially in Africa and Asia, while blue is most often seen in northern and eastern Europe. Green is the rarest of all, found in only about 2% of the global population. Hazel eyes add even more diversity, often appearing to shift between green and brown depending on the light.

So, what lies behind these differences?

It’s all in the melanin

The answer rests in the iris, the coloured ring of tissue that surrounds the pupil. Here, a pigment called melanin does most of the work.

Brown eyes contain a high concentration of melanin, which absorbs light and creates their darker appearance. Blue eyes contain very little melanin. Their colour doesn’t come from pigment at all but from the scattering of light within the iris, a physical effect known as the Tyndall effect, a bit like the effect that makes the sky look blue.

In blue eyes, the shorter wavelengths of light (such as blue) are scattered more effectively than longer wavelengths like red or yellow. Due to the low concentration of melanin, less light is absorbed, allowing the scattered blue light to dominate what we perceive. This blue hue results not from pigment but from the way light interacts with the eye’s structure.

Green eyes result from a balance, a moderate amount of melanin layered with light scattering. Hazel eyes are more complex still. Uneven melanin distribution in the iris creates a mosaic of colour that can shift depending on the surrounding ambient light.

What have genes got to do with it?

The genetics of eye colour is just as fascinating.

For a long time, scientists believed a simple “brown beats blue” model, controlled by a single gene. Research now shows the reality is much more complex. Many genes contribute to determining eye colour. This explains why children in the same family can have dramatically different eye colours, and why two blue-eyed parents can sometimes have a child with green or even light brown eyes.

Eye colour also changes over time. Many babies of European ancestry are born with blue or grey eyes because their melanin levels are still low. As pigment gradually builds up over the first few years of life, those blue eyes may shift to green or brown.

In adulthood, eye colour tends to be more stable, though small changes in appearance are common depending on lighting, clothing, or pupil size. For example, blue-grey eyes can appear very blue, very grey or even a little green depending on ambient light. More permanent shifts are rarer but can occur as people age, or in response to certain medical conditions that affect melanin in the iris.

The real curiosities

Then there are the real curiosities.

Heterochromia, where one eye is a different colour from the other, or one iris contains two distinct colours, is rare but striking. It can be genetic, the result of injury, or linked to specific health conditions. Celebrities such as Kate Bosworth and Mila Kunis are well-known examples. Musician David Bowie’s eyes appeared as different colours because of a permanently dilated pupil after an accident, giving the illusion of heterochromia.

In the end, eye colour is more than just a quirk of genetics and physics. It’s a reminder of how biology and beauty intertwine. Each iris is like a tiny universe, rings of pigment, flecks of gold, or pools of deep brown that catch the light differently every time you look.

Eyes don’t just let us see the world, they also connect us to one another. Whether blue, green, brown, or something in-between, every pair tells a story that’s utterly unique, one of heritage, individuality, and the quiet wonder of being human.![]()

Davinia Beaver, Postdoctoral research fellow, Clem Jones Centre for Regenerative Medicine, Bond University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The science behind a freediver’s 29-minute breath hold world record

Most of us can hold our breath for between 30 and 90 seconds.

A few minutes without oxygen can be fatal, so we have an involuntary reflex to breathe.

But freediver Vitomir Maričić recently held his breath for a new world record of 29 minutes and three seconds, lying on the bottom of a 3-metre-deep pool in Croatia.

This is about five minutes longer than the previous world record set in 2021 by another Croatian freediver, Budimir Šobat.

Interestingly, all world records for breath holds are by freedivers, who are essentially professional breath-holders.

They do extensive physical and mental training to hold their breath under water for long periods of time.

So how do freedivers delay a basic human survival response and how was Maričić able to hold his breath about 60 times longer than most people?

Increased lung volumes and oxygen storage

Freedivers do cardiovascular training – physical activity that increases your heart rate, breathing and overall blood flow for a sustained period – and breathwork to increase how much air (and therefore oxygen) they can store in their lungs.

This includes exercise such as swimming, jogging or cycling, and training their diaphragm, the main muscle of breathing.

Diaphragmatic breathing and cardiovascular exercise train the lungs to expand to a larger volume and hold more air.

This means the lungs can store more oxygen and sustain a longer breath hold.

Freedivers can also control their diaphragm and throat muscles to move the stored oxygen from their lungs to their airways. This maximises oxygen uptake into the blood to travel to other parts of the body.

To increase the oxygen in his lungs even more before his world record breath-hold, Maričić inhaled pure (100%) oxygen for ten minutes.

This gave Maričić a larger store of oxygen than if he breathed normal air, which is only about 21% oxygen.

This is classified as an oxygen-assisted breath-hold in the Guiness Book of World Records.

Even without extra pure oxygen, Maričić can hold his breath for 10 minutes and 8 seconds.

Resisting the reflex to take another breath

Oxygen is essential for all our cells to function and survive. But it is high carbon dioxide, not low oxygen that causes the involuntary reflex to breathe.

When cells use oxygen, they produce carbon dioxide, a damaging waste product.

Carbon dioxide can only be removed from our body by breathing it out.

When we hold our breath, the brain senses the build-up in carbon dioxide and triggers us to breathe again.

Freedivers practice holding their breath to desensitise their brains to high carbon dioxide and eventually low oxygen. This delays the involuntary reflex to breathe again.

When someone holds their breath beyond this, they reach a “physiological break-point”. This is when their diaphragm involuntarily contracts to force a breath.

This is physically challenging and only elite freedivers who have learnt to control their diaphragm can continue to hold their breath past this point.

Indeed, Maričić said that holding his breath longer:

got worse and worse physically, especially for my diaphragm, because of the contractions. But mentally I knew I wasn’t going to give up.

Mental focus and control is essential

Those who freedive believe it is not only physical but also a mental discipline.

Freedivers train to manage fear and anxiety and maintain a calm mental state. They practice relaxation techniques such as meditation, breath awareness and mindfulness.

Interestingly, Maričić said:

after the 20-minute mark, everything became easier, at least mentally.

Reduced mental and physical activity, reflected in a very low heart rate, reduces how much oxygen is needed. This makes the stored oxygen last longer.

That is why Maričić achieved this record lying still on the bottom of a pool.

Don’t try this at home

Beyond competitive breath-hold sports, many other people train to hold their breath for recreational hunting and gathering.

For example, ama divers who collect pearls in Japan, and Haenyeo divers from South Korea who harvest seafood.

But there are risks of breath holding.

Maričić described his world record as:

a very advanced stunt done after years of professional training and should not be attempted without proper guidance and safety.

Indeed, both high carbon dioxide and a lack of oxygen can quickly lead to loss of consciousness.

Breathing in pure oxygen can cause acute oxygen toxicity due to free radicals, which are highly reactive chemicals that can damage cells.

Unless you’re trained in breath holding, it’s best to leave this to the professionals.![]()

Theresa Larkin, Associate Professor of Medical Sciences, University of Wollongong and Gregory Peoples, Senior Lecturer - Physiology, University of Wollongong

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The Third Eye: Moving from Information Age to ‘Age of Intelligence’

New Delhi, (IANS): The success of Information Technology revolution caused the transition of the world from the Industrial Age to the Age of Information but the advent of Artificial Intelligence (AI) is expediting another transformational shift- from the Information Age to the Age of Intelligence propelled by the basic fact that ‘all intelligence is information but all information is not intelligence’.

AI can help detect early larynx cancer from sound of voice: Study

Scientists Regrow Retina Cells to Tackle Leading Cause of Blindness Using Nanotechnology

Researchers Test Use of Nuclear Technology to Curb Rhino Poaching in South Africa

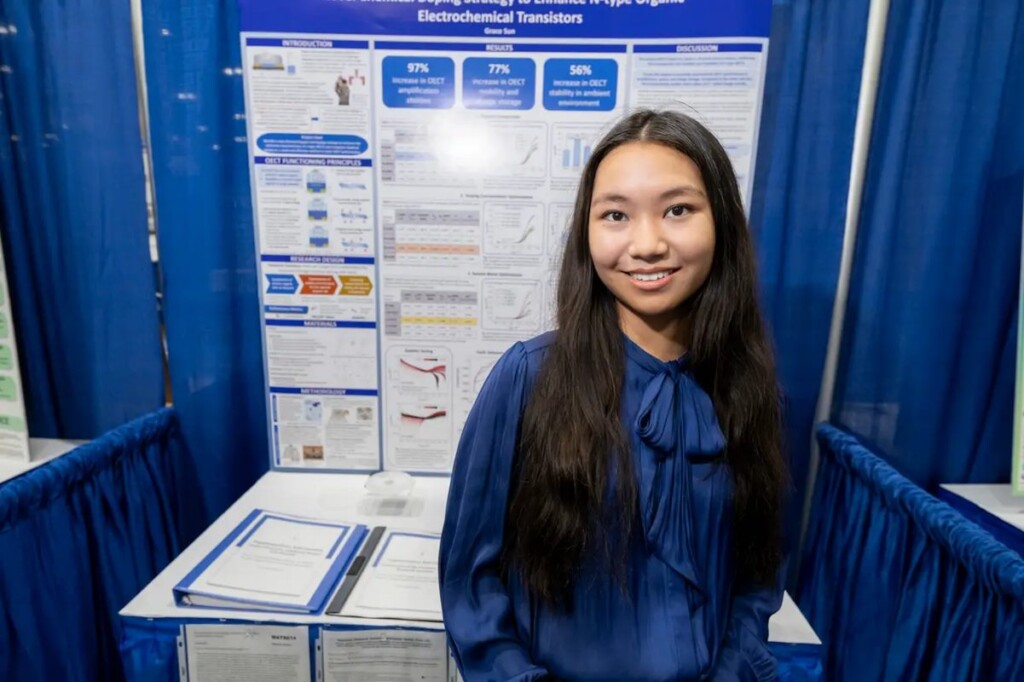

16-year-old Wins $75,000 for Her Award-Winning Discovery That Could Help Revolutionize Biomedical Implants

Grace Sun, credit – Society for Science

Grace Sun, credit – Society for Science