A member of staff works inside ‘Rudy’s Vegan Butcher’ shop, amid the coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak, in London, Britain, October 30, 2020. Picture taken October 30, 2020. REUTERS/Henry Nicholls

A member of staff works inside ‘Rudy’s Vegan Butcher’ shop, amid the coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak, in London, Britain, October 30, 2020. Picture taken October 30, 2020. REUTERS/Henry NichollsScientists studied twins’ diets. Those who ate vegan saw fast results.

A member of staff works inside ‘Rudy’s Vegan Butcher’ shop, amid the coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak, in London, Britain, October 30, 2020. Picture taken October 30, 2020. REUTERS/Henry Nicholls

A member of staff works inside ‘Rudy’s Vegan Butcher’ shop, amid the coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak, in London, Britain, October 30, 2020. Picture taken October 30, 2020. REUTERS/Henry NichollsFieldwork can be challenging for female scientists. Here are 5 ways to make it better

Women coastal scientists face multiple barriers to getting into the field for research. These include negative perceptions of their physical capabilities, not being included in trips, caring responsibilities at home and a lack of field facilities for women. Even if women clear these barriers, the experience can be challenging.

This is a problem because fieldwork is crucial for gathering data, inspiring emerging scientists, developing skills, expanding networks and participating in collaborative research.

Our recent study revisited an international survey of 314 coastal scientists that revealed broad perceptions and experiences of gender inequality in coastal sciences. We offer five ways to improve the fieldwork experience for women.

Our collective experience of more than 70 years as active coastal scientists suggests women face ongoing problems when they go to the field. Against a global backdrop of the #MeToo movement, the Picture a Scientist documentary and media coverage about incidents of sexual harassment in the field, conversations between fieldworkers and research managers about behaviour and policy change are needed.

Our research: what we did and what we found

In 2016, we surveyed both male and female scientists about their experiences of gender equality in coastal sciences during an international symposium in Sydney and afterwards online.

From 314 responses, 113 respondents (36%) provided examples of gender inequality they had either directly experienced or observed while working in coastal sciences. About half of these were related to fieldwork.

Our recent paper in the journal Coastal Futures revisits the survey results to further unpack fieldwork issues that continue to surface among the younger generation of female coastal scientists whom we supervise in our jobs. Many of those younger women don’t know how to address these issues.

The paper includes direct quotes from 18 survey respondents describing their experiences. One woman, a mid-career university researcher, said:

As I fill in this survey, the corridor of the building I work in is lined with empty offices. My colleagues are out on boats doing fieldwork. I have a passion for coastal science. That’s why I’m working in a university. But I have a disproportionately large share of administrative, pastoral and governance duties that keep me from engaging in my passion. I’m about to go to a committee meeting of women, doing women’s work (reviewing teaching offerings). Inequality is alive and well in my workplace!

Collectively, the responses highlight barriers to fieldwork participation and challenges in the field, such as sexual harassment and abuse.

A pressing issue, on and off campus

Universities have recently been criticised for failing to respond to sexual violence on campus. But women employed by universities working off campus – at field sites – can be even more vulnerable.

The social boundaries that characterise day-to-day working life in the office and the laboratory are reconfigured on boats or in field camps. Personal space is reduced. Fieldworkers can be required to sleep in close proximity to one another, potentially putting women in vulnerable situations.

As this female early-career university researcher wrote:

Sometimes women are ‘advised’ to avoid fieldwork for security reasons. Or [we] are considered weak, or we are threatened by rape for being with a lot of men.

Women working on boats commonly face inadequate facilities at sea for toileting, menstruation and managing lactation. Some women said they were “not allowed to join research vessels” or “prevented from [joining] research in the field because of gender”.

Reminded of our personal experiences

Just reading the survey responses was difficult for us. Tales of exclusion and discrimination were particularly confronting because they resonated with our own personal experiences. As one of us, Sarah Hamylton, recalls:

I remember spending a hot day in my early 20s on a small boat taking measurements over a reef. I was the only female. When one of the four guys asked about needing the toilet, he was told to stand and relieve himself off the stern. I had to hold on, so I was desperate when we returned to the main ship in the afternoon.

But that wasn’t the only challenge Hamylton encountered on that trip:

We got back into port and the night before we departed to go home, I was woken by the drunken second officer banging on my cabin door asking for sex. The following year women were banned from attending this annual expedition because someone else had complained about sexual assault.

Gender stereotypes and discrimination

Coastal fieldwork demands diverse physical skills such as boating, four-wheel driving, towing trailers, working with hand and power tools, moving heavy equipment, SCUBA diving and being comfortable swimming in the surf, in currents or underwater.

But our survey revealed roles on field trips – and therefore opportunities to learn and gain crucial field skills – are typically handed to men rather than women. Several respondents observed female students and staff being left out of field work for “not being strong enough” and “too weak to pick stuff up”.

Body exposure can also be an issue for women in the field. Close-fitting wetsuits and swimsuits can increase the likelihood of womens’ bodies being objectified by colleagues. Undertaking coastal fieldwork while menstruating can also be a concern.

Another of us, Ana Vila-Concejo, notes:

Some scientific presentations show women in bikinis as a ‘beach modelling’ joke. Beyond self-consciousness, I have felt vulnerable wearing swimmers and exerting myself during fieldwork. Women students and volunteers have declined to participate in field experiments for this reason, particularly while menstruating.

The issue of body exposure also sheds light on the interconnections between race, religion, class and sexuality, which can create overlapping and intersectional disadvantages for women. Vila-Concejo adds:

I am old enough now that I don’t care anymore. I can afford a wetsuit, but many students and volunteers don’t have one. For some women, it isn’t socially or culturally acceptable to wear swimmers, or even to do fieldwork.

Five suggestions for improvement

To improve the fieldwork experience for women in coastal sciences, our research found the following behavioural and policy changes are needed:

publicise field role models and trailblazers to reshape public views of coastal scientists, increasing the visibility of female fieldworkers

improve opportunities and capacity for women to undertake fieldwork to diversify field teams by identifying and addressing the intersecting disadvantages experienced by women

establish field codes of conduct that outline acceptable standards of behaviour on field trips, what constitutes misconduct, sexual harassment and assault, how to make an anonymous complaint and disciplinary measures

acknowledge the challenges women face in the field and provide support where possible in fieldwork briefings and address practical challenges for women in remote locations, including toileting and menstruation

foster an enjoyable and supportive fieldwork culture that emphasises mutual respect, safety, inclusivity, and collegiality on every trip.

These five simple steps will improve the experience of fieldwork for all concerned and ultimately benefit the advancement of science.![]()

Sarah Hamylton, Associate professor, University of Wollongong; Ana Vila Concejo, Associate professor, University of Sydney; Hannah Power, Associate Professor in Coastal and Marine Science, University of Newcastle, and Shari L Gallop, Service Leader - Coastal, University of Waikato

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Indian American scientist hoping to be first woman to jump from stratosphere

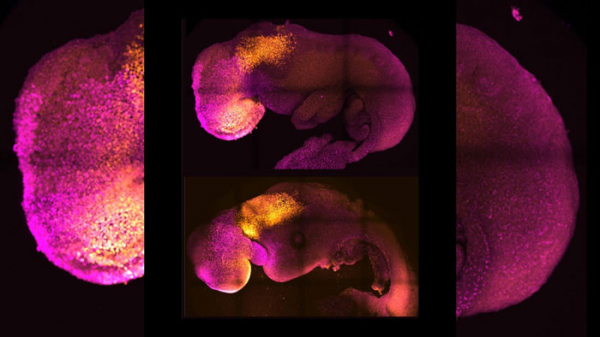

A synthetic embryo, made without sperm, could lead to infertility

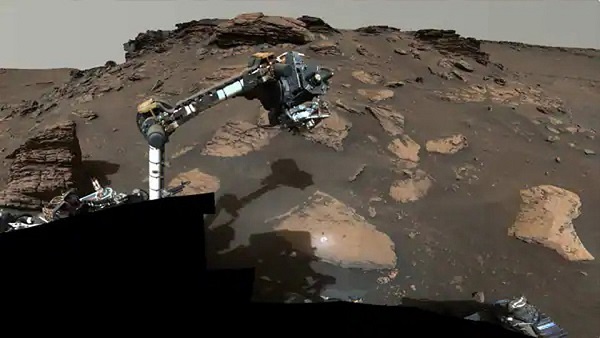

Mars rover sees hints of past life in latest rock samples