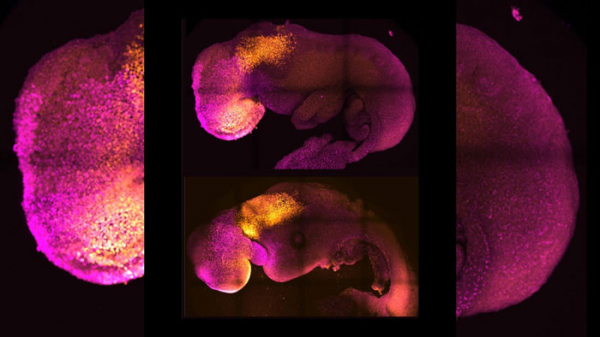

A synthetic embryo, made without sperm or egg, could lead to infertility treatments

Scientists have created mouse embryos in a dish, and it could one day help families hoping to get pregnant, according to a new study.

After 10 years of research, scientists created a synthetic mouse embryo that began forming organs without a sperm or egg, according to the study published Thursday in the journal Nature. All it took was stem cells.

Stem cells are unspecialized cells that can be manipulated into becoming mature cells with special functions.

"Our mouse embryo model not only develops a brain, but also a beating heart, all the components that go on to make up the body," said lead study author Magdalena Zernicka-Goetz, professor of mammalian development and stem cell biology at the University of Cambridge in the United Kingdom.

"It's just unbelievable that we've got this far. This has been the dream of our community for years, and a major focus of our work for a decade, and finally we've done it."

The paper is an exciting advance and tackles a challenge scientists face studying mammal embryos in utero, said Marianne Bronner, a professor of biology at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena (Caltech). Bronner was not involved in the study.

"These develop outside of the mother and therefore can be easily visualized through critical developmental stages that were previously difficult to access," Bronner added.

The researchers hope to move from mouse embryos to creating models of natural human pregnancies -- many of which fail in the early stages, Zernicka-Goetz said.

By watching the embryos in a lab instead of a uterus, scientists got a better view into the process to learn why some pregnancies might fail and how to prevent it, she added.

For now, researchers have only been able to track about eight days of development in the mouse synthetic embryos, but the process is improving, and they are already learning a lot, said study author Gianluca Amadei, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Cambridge.

"It reveals the fundamental requirements that have to be fulfilled to make the right structure of the embryo with its organs," Zernicka-Goetz said.

Where it stands, the research doesn't apply to humans and "there needs to be a high degree of improvement for this to be truly useful," said Benoit Bruneau, the director of the Gladstone Institute of Cardiovascular Disease and a senior investigator at Gladstone Institutes. Bruneau was not involved in the study.

But researchers see important uses for the future. The process can be used immediately to test new drugs, Zernicka-Goetz said. But in the longer term, as scientists move from mouse synthetic embryos to a human embryo model, it also could help build synthetic organs for people who need transplants, Zernicka-Goetz added.

"I see this work as being the first example of work of this kind," said study author David Glover, research professor of biology and biological engineering at Caltech.

How they did it

In utero, an embryo needs three types of stem cells to form: One becomes the body tissue, another the sac where the embryo develops, and the third the placenta connecting parent and fetus, according to the study.

In Zernicka-Goetz's lab, researchers isolated the three types of stem cells from embryos and cultured them in a container angled to bring the cells together and encourage crosstalk between them.

Day by day, they were able to see the group of cells form into a more and more complex structure, she said.

There are ethical and legal considerations to address before moving to human synthetic embryos, Zernicka-Goetz said. And with the difference in complexity between mouse and human embryos, it could be decades before researchers are able to do a similar process for human models, Bronner said.

But in the meantime, the information learned from the mouse models could help "correct failing tissues and organs," Zernicka-Goetz said.

The mystery of human life

The early weeks after fertilization are made up of these three different stem cells communicating with one another chemically and mechanically so the embryo can grow properly, the study said.

"So many pregnancies fail around this time, before most women (realize) they are pregnant," said Zernicka-Goetz, who is also professor of biology and biological engineering at Caltech. "This period is the foundation for everything else that follows in pregnancy. If it goes wrong, the pregnancy will fail."

But by this stage, an embryo created through in vitro fertilization is already implanted in the parent, so scientists have limited visibility into the processes it is going through, Zernicka-Goetz said.

They were able to develop foundations of a brain -- a first for models such as these and a "holy grail for the field," Glover said.

"This period of human life is so mysterious, so to be able to see how it happens in a dish -- to have access to these individual stem cells, to understand why so many pregnancies fail and how we might be able to prevent that from happening -- is quite special," Zernicka-Goetz said in a press release. "We looked at the dialogue that has to happen between the different types of stem cell at that time -- we've shown how it occurs and how it can go wrong."-