Volcanic ash plume from Ethiopia moving over North India will not impact AQI: Experts

Researchers Test Use of Nuclear Technology to Curb Rhino Poaching in South Africa

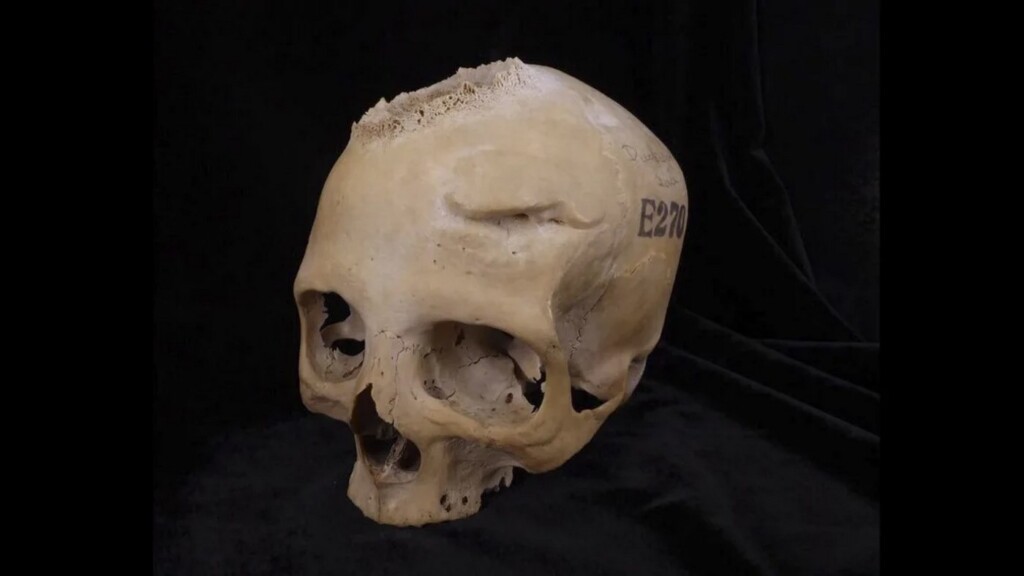

Egyptians Performed Brain Surgery 4,000 years ago: A Discovery Called a ‘Milestone in the History of Medicine’

Evidence of the man’s malignant tumor – supplied by Tondini, Isidro, Camarós

Evidence of the man’s malignant tumor – supplied by Tondini, Isidro, Camarós Skull E270 – supplied by Tondini, Isidro, Camarós

Skull E270 – supplied by Tondini, Isidro, CamarósResearchers Test Use of Nuclear Technology to Curb Rhino Poaching in South Africa

South Africa Bans Commercial Fishing at Penguin Breeding Spots Where Food Supply Shortage Could Drive Extinction

African penguins on a Cape Coast beach – credit S Martin, CC 2.0., via Flickr

African penguins on a Cape Coast beach – credit S Martin, CC 2.0., via FlickrCameroon islands offer safe home for orphaned chimps

Nigeria’s last elephants – what must be done to save them

Nigeria has a unique elephant population, made up of both forest-dwelling (Loxodonta cyclotis) and savanna-dwelling (Loxodonta africana) elephant species. But the animals are facing unprecedented threats to their survival. In about 30 years, Nigeria’s elephant population has crashed from an estimated 1,200-1,500 to an estimated 300-400 today. About 200-300 are forest elephants and 100 savanna elephants.

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) recently classified the forest elephant as “critically endangered” and the savanna elephant as “endangered”.

The country has never had herds in the multiple thousands, but its elephants have played a vital ecological role, balancing natural ecosystems.

Today they live primarily in protected areas and in small forest fragments where they are increasingly isolated and vulnerable to extinction. They are found in Chad Basin National Park in Borno State and Yankari Game Reserve in Bauchi State. Also in Omo Forests Reserve in Ogun State, Okomu National Park in Edo State and Cross River National Park in Cross River State.

Elephants in Nigeria are threatened by habitat loss and fragmentation, poaching and illegal ivory trade, human-elephant conflict and climate change. These issues are pushing them to the brink of extinction.

In August 2024 Nigeria launched the country’s first National Elephant Action Plan. The 10-year strategic plan aims to ensure the long-term survival of elephants in Nigeria.

But will it?

As a conservationist with research in elephant conservation, I think this plan is a promising initiative. It could ensure the survival of Nigeria’s elephants. However, the long-term sustainability of the elephant populations in Nigeria depends on how well the plan balances conservation efforts with economic development. The government must also be willing to support the plan. It must commit financial resources to carry out the plan.

Here I set out the threats to elephants in Nigeria and four urgent steps needed to save these animals. Taking these steps will help make the strategic plan a reality.

Threats to elephants in Nigeria

Expansion of agriculture, urbanisation and infrastructure development leads to habitat loss and fragmentation. The destruction of elephant habitats means that populations are isolated. This has made it difficult for the animal to migrate, find food and breed. At about 3.5% a year, the rate of forest loss in Nigeria is among the highest globally.

Poaching of elephants for their ivory and traditional medicinal value is another menace. Despite the ivory trade ban under the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species, Nigeria-linked ivory seizures amounted to 12,211kg in the period 2015-2017. In January 2024, Nigeria destroyed 2.5 tonnes of seized elephant tusks valued at over 9.9 billion naira (US$11.2 million).

Human-elephant conflict is a growing challenge. As elephants lose their habitats, they encroach on farmland, leading to conflicts with people. Elephants damage crops. In retaliation, some communities harm or kill the elephants.

Climate change is another threat to the survival of elephants in the country. Water scarcity and food insecurity affect both humans and elephants. Elephants are forced to venture into human-dominated landscapes, increasing conflicts.

Saving endangered elephants in Nigeria

To save its elephants, Nigeria needs to take the following steps.

Strengthen existing protected areas: It is important to restore and safeguard elephants’ habitats. Existing national parks, forest and game reserves should be strengthened to prevent further destruction and fragmentation. Wildlife corridors to reconnect fragmented populations are also crucial. This should be based on management plans approved by government agencies, conservationists and local communities.

Combat poaching and ivory trafficking: Wildlife laws must be enforced to disrupt the ivory trade networks. The capacity of park rangers, wildlife law enforcers and local authorities to combat poaching must be enhanced. Advanced surveillance tools such as drones and camera traps must be provided. There should also be regular training for law enforcement officers to keep up with modern anti-poaching tactics.

Stricter penalties for wildlife crimes and effective prosecution of offenders will deter poachers too.

Promote human-elephant coexistence: This requires innovative and community-driven solutions.

One approach is the use of early warning systems and deterrent measures, such as beehive fences. They have been effective in deterring elephants from entering farmlands. Training and equipping local communities to monitor elephant movements can also help avoid conflicts. Compensation schemes for farmers who suffer losses from elephant raids can foster positive attitudes towards conservation.

Expanding public awareness and conservation education: Some Nigerians may not fully understand the ecological and cultural importance of elephants. Awareness of their role in maintaining ecosystem health and the consequences of their extinction is key to fostering support for protection.

Schools, community groups and media should be engaged in conservation education initiatives. This will promote a sense of ownership and responsibility for preserving Nigeria’s wildlife generally.

Why Nigeria must save its elephants

Saving elephants is not only a matter of preserving biodiversity but also ensuring the health of entire ecosystems.

Elephants are keystone species; they create and maintain habitats that support other species. They shape the landscape, disperse seeds, and create water holes that benefit a wide variety of wildlife. Losing them would have cascading effects on the environment.

Economically, elephants are valuable for ecotourism. They can provide sustainable income to local communities. Protecting elephants could be an alternative to poaching or illegal logging.

Culturally, elephants hold symbolic and spiritual value for many Nigerians. Their presence is linked to heritage and identity of communities.

Protecting elephants in Nigeria is not only about conserving a species. It is about preserving the country’s ecological integrity, supporting sustainable livelihoods, and safeguarding the natural heritage for future generations. The time to act is now.![]()

Tajudeen Amusa, Professor, Forest Resources Management, University of Ilorin

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Egypt Has Finally Been Declared Malaria-Free After 4,000 Years of Infections—Even the Pharaohs

Cairo on the Nile – Photo by Jack Krier on Unsplash

Cairo on the Nile – Photo by Jack Krier on UnsplashNamibia's drought cull of more than 700 wildlife under way

The First of 2,000 Privately Owned White Rhinos Get New Home – Rewilded by South African Conservancy

South Africa’s great white sharks are changing locations – they need to be monitored for beach safety and conservation

In Cape Town, skilled “shark spotters” documented a peak of over 300 great white shark sightings across eight beaches in 2011, but have recorded no sightings since 2019. These declines have sparked concerns about the overall conservation status of the species.

Conserving great white sharks is vital because they have a pivotal role in marine ecosystems. As top predators, they help maintain the health and balance of marine food webs. Their presence influences the behaviour of other marine animals, affecting the entire ecosystem’s structure and stability.

Marine biologists like us needed to know whether the decline in shark numbers in the Western Cape indicated changes in the whole South African population or whether the sharks had moved to a different location.

To investigate this problem, we undertook an extensive study using data collected by scientists, tour operators and shore anglers. We examined the trends over time in abundance and shifts in distribution across the sharks’ South African range.

Our investigation revealed significant differences in the abundance at primary gathering sites. There were declines at some locations; others showed increases or stability. Overall, there appears to be a stable trend. This suggests that white shark numbers have remained constant since they were given protection in 1991.

Looking at the potential change in the distribution of sharks between locations, we discovered a shift in human-shark interactions from the Western Cape to the Eastern Cape. More research is required to be sure whether the sharks that vanished from the Western Cape are the same sharks documented along the Eastern Cape.

The stable population of white sharks is reassuring, but the distribution shift introduces its own challenges, such as the risk posed by fisheries, and the need for beach management. So there is a need for better monitoring of where the sharks are.

Factors influencing shark movements

We recorded the biggest changes between 2015 and 2020. For example, at Seal Island, False Bay (Western Cape), shark sightings declined from 2.5 sightings per hour in 2005 to 0.6 in 2017. Shifting eastward to Algoa Bay, in 2013, shore anglers caught only six individual sharks. By 2019, this figure had risen to 59.

The changes at each site are complex, however. Understanding the patterns remains challenging.

These predators can live for more than 70 years. Each life stage comes with distinct behaviours: juveniles, especially males, tend to stay close to the coastline, while sub-adults and adults, particularly females, venture offshore.

Environmental factors like water temperature, lunar phase, season and food availability further influence their movement patterns.

Changes in the climate and ocean over extended periods might also come into play.

As adaptable predators, they target a wide range of prey and thrive in a broad range of temperatures, with a preference for 14–24°C. Their migratory nature allows them to seek optimal conditions when faced with unfavourable environments.

Predation of sharks by killer whales

The movement complexity deepens with the involvement of specialist killer whales with a taste for shark livers. Recently, these apex predators have been observed preying on white, sevengill and bronze whaler sharks.

Cases were first documented in 2015 along the South African coast, coinciding with significant behavioural shifts in white sharks within Gansbaai and False Bay.

Although a direct cause-and-effect link is not firmly established, observations and tracking data support the notion of a distinct flight response among white sharks following confirmed predation incidents.

More recently, it was clear that in Mossel Bay, when a killer whale pod killed at least three white sharks, the remaining sharks were prompted to leave the area.

Survival and conservation of sharks

The risk landscape for white sharks is complex. A study published in 2022 showed a notable overlap of white sharks with longline and gillnet fisheries, extending across 25% of South Africa’s Exclusive Economic Zone. The sharks spent 15% of their time exposed to these fisheries.

The highest white shark catches were reported in KwaZulu-Natal, averaging around 32 per year. This emphasised the need to combine shark movement with reliable catch records to assess risks to shark populations.

As shark movement patterns shift eastward, the potential change in risk must be considered. Increased overlap between white sharks, shark nets, drumlines (baited hooks) and gillnets might increase the likelihood of captures.

Beach safety and management adaptation

Although shark bites remain a low risk, changing shark movements could also influence beach safety. The presence of sharks can influence human activities, particularly in popular swimming and water sports areas. Adjusting existing shark management strategies might be necessary as distributions change.

Increased signage, temporary beach closures, or improved education about shark behaviour might be needed.

In Cape Town, for example, shark spotters have adjusted their efforts on specific beaches. Following two fatal shark incidents in 2022, their programme expanded to Plettenberg Bay. Anecdotal evidence highlights additional Eastern Cape locations where surfers and divers encounter more white sharks than before.

Enhanced monitoring and long-term programmes

Further research is required to understand the factors behind the movements of sharks and their impact on distribution over space and time. Our study underscores the importance of standardising data collection methods to generate reliable abundance statistics across their entire range. Other countries suffer from the same problem.

Additionally, we propose establishing long-term monitoring programmes along the Eastern Cape and continuing work to reduce the number of shark deaths.

Sarah Waries, a master’s student and CEO of Shark Spotters in Cape Town, contributed to this article.![]()

Alison Kock, Marine Biologist, South African National Parks (SANParks); Honorary Research Associate, South African Institute for Aquatic Biodiversity (SAIAB), South African Institute for Aquatic Biodiversity; Alison Towner, Marine biologist, Rhodes University; Heather Bowlby, Research Lead, Fisheries and Oceans Canada; Matt Dicken, Adjunct Professor of Marine Biology, Nelson Mandela University, and Toby Rogers, PhD Candidate, University of Cape Town

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Asteroid claims to have destroyed dinosaurs in African seas

Mutated virus variant from South Africa found in UK

World's second largest rainforest at risk from lifting of logging moratorium

Russia Developing Terrorist-Killer Robots

4 Million Year Old Menu: What Our Ancestors Ate

The diet of Australopithecus anamensis, a hominid that lived in the east of the African continent more than 4 million years ago, was very specialized and, according to a scientific study whose principal author is Ferran Estebaranz, from the Department of Animal Biology at the University of Barcelona, it included foods typical of open environments (seeds, sedges, grasses, etc.), as well as fruits and tubers.

Ebola vaccine is 100% successful

Recipient of world’s first penis implant to be a dad

How do Birds get their Color?