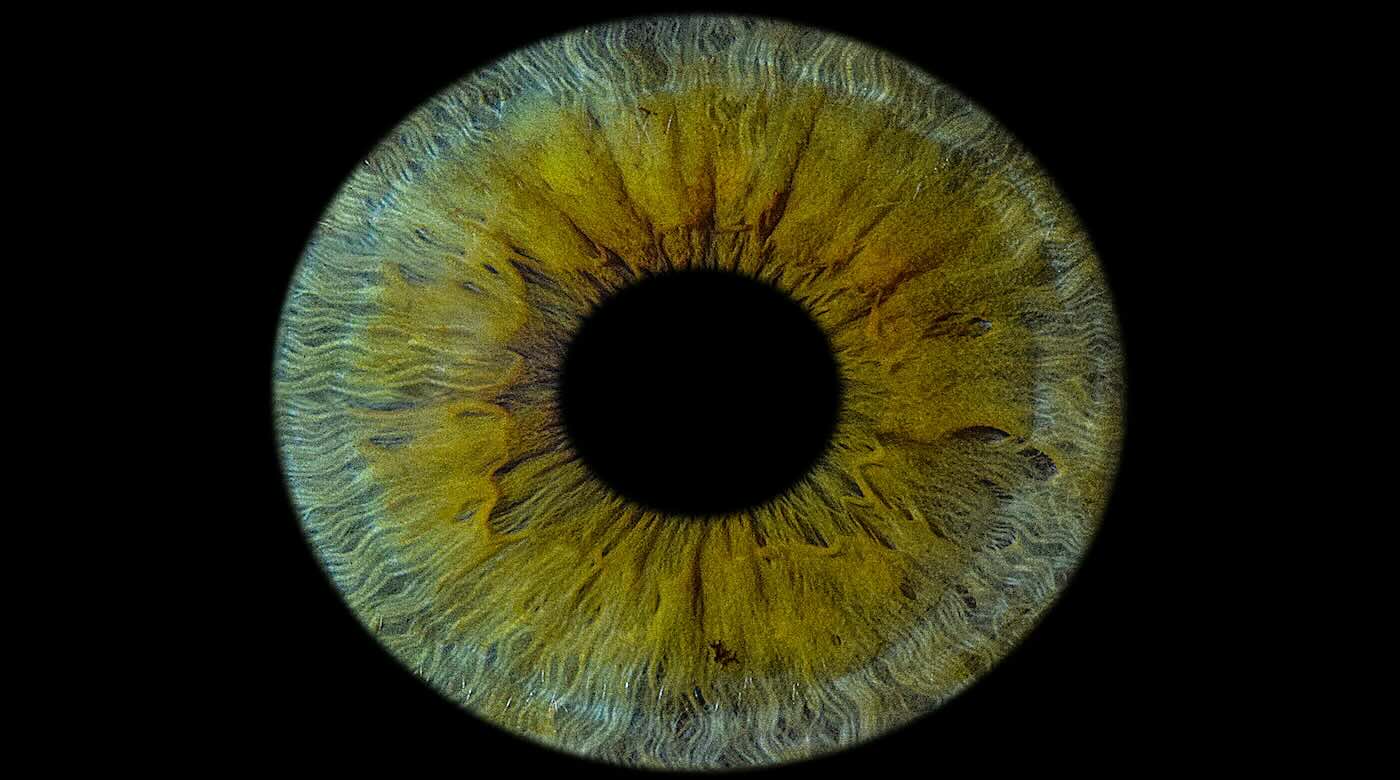

The first successful human implant of a 3D-printed cornea made from human eye cells cultured in a laboratory has restored a patient’s sight.

The North Carolina-based company that developed the cornea described the procedure as a ‘world first’—and a major milestone toward its goal of alleviating the lack of available donor tissue and long wait-times for people seeking transplants.

According to Precise Bio, its robotic bio-fabrication approach could potentially turn a single donated cornea into hundreds of lab-grown grafts, at a time when there’s currently only one available for an estimated 70 patients who need one to see.

“This achievement marks a turning point for regenerative ophthalmology—a moment of real hope for millions living with corneal blindness,” Aryeh Batt, Precise Bio’s co-founder and CEO, said in a statement.

“For the first time, a corneal implant manufactured entirely in the lab from cultured human corneal cells, rather than direct donor tissue, has been successfully implanted in a patient.”

The company said the transplant was performed Oct. 29 in one eye of a patient who was considered legally blind.

“This is a game changer. We’ve witnessed a cornea created in the lab, from living human cells, bring sight back to a human being,” said Dr. Michael Mimouni, director of the cornea unit at Rambam Medical Center in Israel, who performed the procedure.

“It was an unforgettable moment—a glimpse into a future where no one will have to live in darkness because of a shortage of donor tissue.”

Dubbed PB-001, the implant is designed to match the optical clarity, transparency and bio-mechanical properties of a native cornea. Previously tested in animal models, the company said its graft is capable of integrating with a patient’s own tissue.

The outer layer of the eye—covering the iris and pupil—can end up clouding a person’s vision following injuries, infections, scarring and other conditions. PB-001 is currently being tested in a single-arm phase 1 trial in Israel, which aims to enroll between 10 and 15 participants with excess fluid buildups in the cornea due to dysfunction within its inner cell layers.

Precise Bio said it plans to announce top-line results from the study in the second half of 2026, tracking six-month efficacy outcomes.

The corneas are designed to be compatible with current surgery hardware and workflows. Shipped under long-term cryopreservation, it is delivered preloaded on standard delivery devices and unrolls during implantation to form a natural corneal shape.

“PB-001 has the potential to offer a new, standardized solution to one of ophthalmology’s most urgent needs—reliable, safe, and effective corneal replacement,” said Anthony Atala, M.D., co-founder of Precise Bio and director of the Wake Forest Institute for Regenerative Medicine.

“The ability to produce patient-ready tissue on demand could lead the way towards reshaping transplant medicine as we know it.”(Edited from original article by Conor Hale) First Human Cornea Transplant Using 3D Printed, Lab-Grown Tissue Restores Sight in a ‘Game Changer’ for Millions Who are Blind

Photo by Hamish on Unsplash

Photo by Hamish on Unsplash Worms collected in the Chornobyl Exclusion Zone – SWNS / New York University

Worms collected in the Chornobyl Exclusion Zone – SWNS / New York University