Time of day may determine heart surgery outcomes: Study

2025 Was 'Year of the Octopus' Says UK Wildlife Trust, Amid Record Cephalopod Sightings

It was 75 years ago the last time there were as many octopus in British waters as there are now, with the UK’s Wildlife Trusts declaring that 2025 was the ‘Year of the Octopus.’

These eight-legged spineless creatures, one of the most fascinating to inhabit our planet, have been seen in record numbers by divers, and caught in record amounts by commercial fishermen.

Scientists suggest it could be milder winters leading to the “bloom,” which is the term for octopus birthing seasons.

“It really has been exceptional,” says Matt Slater from the Cornwall Wildlife Trust. “We’ve seen octopuses jet-propelling themselves along. We’ve seen octopuses camouflaging themselves, they look just like seaweeds,” he told the BBC.

“We’ve seen them cleaning themselves. And we’ve even seen them walking, using two legs just to nonchalantly cruise away from the diver underwater.”

Regarding the fisheries, it’s been a banner year for the industry. 2021 and 2023 have seen the highest yearly catches recently, when around 200 metric tons were landed. This year it was 12-times that amount.

Interestingly, their chief prey species, lobsters, crayfish, and scallops, have maintained year-over-year populations, with only crab falling.

It’s up to scientists now to figure out whether this octopu-nanza is part of a one-off event, or something that will be a more permanent feature of British seas. If the suggestion that warmer winters may be behind the massive bloom, future hatching seasons could be similarly large.While it may be premature to celebrate an unusual effect that seems tied to climate change, it’s hard to argue with the smiles on the faces of the divers, the diners, and the fishermen. 2025 Was 'Year of the Octopus' Says UK Wildlife Trust, Amid Record Cephalopod Sightings

Polar bears are adapting to climate change at a genetic level – and it could help them avoid extinction

But in our new study my colleagues and I found that the changing climate was driving changes in the polar bear genome, potentially allowing them to more readily adapt to warmer habitats. Provided these polar bears can source enough food and breeding partners, this suggests they may potentially survive these new challenging climates.

We discovered a strong link between rising temperatures in south-east Greenland and changes in polar bear DNA. DNA is the instruction book inside every cell, guiding how an organism grows and develops. In processes called transcription and translation, DNA is copied to generate RNA (molecules that reflect gene activity) and can lead to the production of proteins, and copies of transposons (TEs), also known as “jumping genes”, which are mobile pieces of the genome that can move around and influence how other genes work.

In carrying out our recent research we found that there were big differences in the temperatures observed in the north-east, compared with the south-east regions of Greenland. Our team used publicly available polar bear genetic data from a research group at the University of Washington, US, to support our study. This dataset was generated from blood samples collected from polar bears in both northern and south-eastern Greenland.

Our work built on the Washington University study which discovered that this south-eastern population of Greenland polar bears was genetically different to the north-eastern population. South-east bears had migrated from the north and became isolated and separate approximately 200 years ago, it found.

Researchers from Washington had extracted RNA from polar bear blood samples and sequenced it. We used this RNA sequencing to look at RNA expression — the molecules that act like messengers, showing which genes are active, in relation to the climate. This gave us a detailed picture of gene activity, including the behaviour of TEs. Temperatures in Greenland have been closely monitored and recorded by the Danish Meteorological Institute. So we linked this climate data with the RNA data to explore how environmental changes may be influencing polar bear biology.

Does temperature change anything?

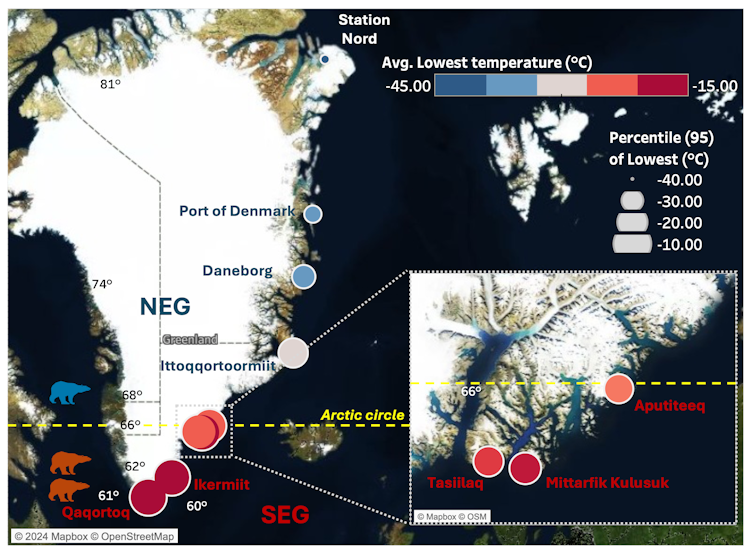

From our analysis we found that temperatures in the north-east of Greenland were colder and less variable, while south-east temperatures fluctuated and were significantly warmer. The figure below shows our data as well as how temperature varies across Greenland, with warmer and more volatile conditions in the south-east. This creates many challenges and changes to the habitats for the polar bears living in these regions.

In the south-east of Greenland, the ice-sheet margin, which is the edge of the ice sheet and spans 80% of Greenland, is rapidly receding, causing vast ice and habitat loss.

The loss of ice is a substantial problem for the polar bears, as this reduces the availability of hunting platforms to catch seals, leading to isolation and food scarcity. The north-east of Greenland is a vast, flat Arctic tundra, while south-east Greenland is covered by forest tundra (the transitional zone between coniferous forest and Arctic tundra). The south-east climate has high levels of rain, wind, and steep coastal mountains.

Temperature across Greenland and bear locations

Author data visualisation using temperature data from the Danish Meteorological Institute. Locations of bears in south-east (red icons) and north-east (blue icons). CC BY-NC-ND

Author data visualisation using temperature data from the Danish Meteorological Institute. Locations of bears in south-east (red icons) and north-east (blue icons). CC BY-NC-NDHow climate is changing polar bear DNA

Over time the DNA sequence can slowly change and evolve, but environmental stress, such as warmer climate, can accelerate this process.

TEs are like puzzle pieces that can rearrange themselves, sometimes helping animals adapt to new environments. In the polar bear genome approximately 38.1% of the genome is made up of TEs. TEs come in many different families and have slightly different behaviours, but in essence they all are mobile fragments that can reinsert randomly anywhere in the genome.

In the human genome, 45% is comprised of TEs and in plants it can be over 70%. There are small protective molecules called piwi-interacting RNAs (piRNAs) that can silence the activity of TEs.

Despite this, when an environmental stress is too strong, these protective piRNAs cannot keep up with the invasive actions of TEs. In our work we found that the warmer south-east climate led to a mass mobilisation from these TEs across the polar bear genome, changing its sequence. We also found that these TE sequences appeared younger and more abundant in the south-east bears, with over 1,500 of them “upregulated”, which suggests recent genetic changes that may help bears adapt to rising temperatures.

Some of these elements overlap with genes linked to stress responses and metabolism, hinting at a possible role in coping with climate change. By studying these jumping genes, we uncovered how the polar bear genome adapts and responds, in the shorter term, to environmental stress and warmer climates.

Our research found that some genes linked to heat-stress, ageing and metabolism are behaving differently in the south-east population of polar bears. This suggests they might be adjusting to their warmer conditions. Additionally, we found active jumping genes in parts of the genome that are involved in areas tied to fat processing – important when food is scarce. This could mean that polar bears in the south-east are slowly adapting to eating the rougher plant-based diets that can be found in the warmer regions. Northern populations of bears eat mainly fatty seals.

Overall, climate change is reshaping polar bear habitats, leading to genetic changes, with south-eastern bears evolving to survive these new terrains and diets. Future research could include other polar bear populations living in challenging climates. Understanding these genetic changes help researchers see how polar bears might survive in a warming world – and which populations are most at risk.

Don’t have time to read about climate change as much as you’d like?

Get a weekly roundup in your inbox instead. Every Wednesday, The Conversation’s environment editor writes Imagine, a short email that goes a little deeper into just one climate issue. Join the 47,000+ readers who’ve subscribed so far.![]()

Alice Godden, Senior Research Associate, School of Biological Sciences, University of East Anglia

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Engineer Powers Entire Home Using 500 Discarded Vapes–Documented in Fascinating Viral Video

Boy with Rare Genetic Disorder Amazes Doctors After World-First Gene Therapy

Courtesy of Oliver Chu family

Courtesy of Oliver Chu familyRecyclers Switch from Smelting to Solvents, Recovering Precious Metals from E-waste with Fewer Emissions

Birth of UK's Only Bonobo Baby Gives Fresh Hope for World's Most Endangered Ape

credit – Adam Kay, Twycross Zoo / SWNS

credit – Adam Kay, Twycross Zoo / SWNSPoor sleep may make your brain age faster – new study

Abigail Dove, Karolinska Institutet

We spend nearly a third of our lives asleep, yet sleep is anything but wasted time. Far from being passive downtime, it is an active and essential process that helps restore the body and protect the brain. When sleep is disrupted, the brain feels the consequences – sometimes in subtle ways that accumulate over years.

In a new study, my colleagues and I examined sleep behaviour and detailed brain MRI scan data in more than 27,000 UK adults between the ages of 40 and 70. We found that people with poor sleep had brains that appeared significantly older than expected based on their actual age.

What does it mean for the brain to “look older”? While we all grow chronologically older at the same pace, some people’s biological clocks can tick faster or slower than others. New advances in brain imaging and artificial intelligence allow researchers to estimate a person’s brain age based on patterns in brain MRI scans, such as loss of brain tissue, thinning of the cortex and damage to blood vessels.

In our study, brain age was estimated using over 1,000 different imaging markers from MRI scans. We first trained a machine learning model on the scans of the healthiest participants – people with no major diseases, whose brains should closely match their chronological age. Once the model “learned” what normal ageing looks like, we applied it to the full study population.

Having a brain age higher than your actual age can be a signal of departure from healthy ageing. Previous research has linked an older-appearing brain to faster cognitive decline, greater dementia risk and even higher risk of early death.

Sleep is complex, and no single measure can tell the whole story of a person’s sleep health. Our study, therefore, focused on five aspects of sleep self-reported by the study participants: their chronotype (“morning” or “evening” person), how many hours they typically sleep (seven to eight hours is considered optimal), whether they experience insomnia, whether they snore and whether they feel excessively sleepy during the day.

These characteristics can interact in synergistic ways. For example, someone with frequent insomnia may also feel more daytime sleepiness, and having a late chronotype may lead to shorter sleep duration. By integrating all five characteristics into a “healthy sleep score”, we captured a fuller picture of overall sleep health.

People with four or five healthy traits had a “healthy” sleep profile, while those with two to three had an “intermediate” profile, and those with zero or one had a “poor” profile.

When we compared brain age across different sleep profiles, the differences were clear. The gap between brain age and chronological age widened by about six months for every one point decrease in healthy sleep score. On average, people with a poor sleep profile had brains that appeared nearly one year older than expected based on their chronological age, while those with a healthy sleep profile showed no such gap.

We also considered the five sleep characteristics individually: late chronotype and abnormal sleep duration stood out as the biggest contributors to faster brain ageing.

A year may not sound like much, but in terms of brain health, it matters. Even small accelerations in brain ageing can compound over time, potentially increasing the risk of cognitive impairment, dementia and other neurological conditions.

The good news is that sleep habits are modifiable. While not all sleep problems are easily fixed, simple strategies: keeping a regular sleep schedule; limiting caffeine, alcohol and screen use before bedtime; and creating a dark and quiet sleep environment can improve sleep health and may protect brain health.

One explanation may be inflammation. Increasing evidence suggests that sleep disturbances raise the level of inflammation in the body. In turn, inflammation can harm the brain in several ways: damaging blood vessels, triggering the buildup of toxic proteins and speeding up brain cell death.

We were able to investigate the role of inflammation thanks to blood samples collected from participants at the beginning of the study. These samples contain a wealth of information about different inflammatory biomarkers circulating in the body. When we factored this into our analysis, we found that inflammation levels accounted for about 10% of the connection between sleep and brain ageing.

Other processes may also play a role

Another explanation centres on the glymphatic system – the brain’s built-in waste clearance network, which is mainly active during sleep. When sleep is disrupted or insufficient, this system may not function properly, allowing harmful substances to build up in the brain.

Yet another possibility is that poor sleep increases the risk of other health conditions that are themselves damaging for brain health, including type 2 diabetes, obesity and cardiovascular disease.

Our study is one of the largest and most comprehensive of its kind, benefiting from a very large study population, a multidimensional measure of sleep health, and a detailed estimation of brain age through thousands of brain MRI features. Though previous research connected poor sleep to cognitive decline and dementia, our study further demonstrated that poor sleep is tied to a measurably older-looking brain, and inflammation might explain this link.

Brain ageing cannot be avoided, but our behaviour and lifestyle choices can shape how it unfolds. The implications of our research are clear: to keep the brain healthier for longer, it is important to make sleep a priority.![]()

Abigail Dove, Postdoctoral Researcher, Neuroepidemiology, Karolinska Institutet

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The Subtle Power of Unhearable Sound: Mood and Cognition-Altering Agents

First Light Fusion presents novel approach to fusion

_89230.jpg) (Image: First Light Fusion)

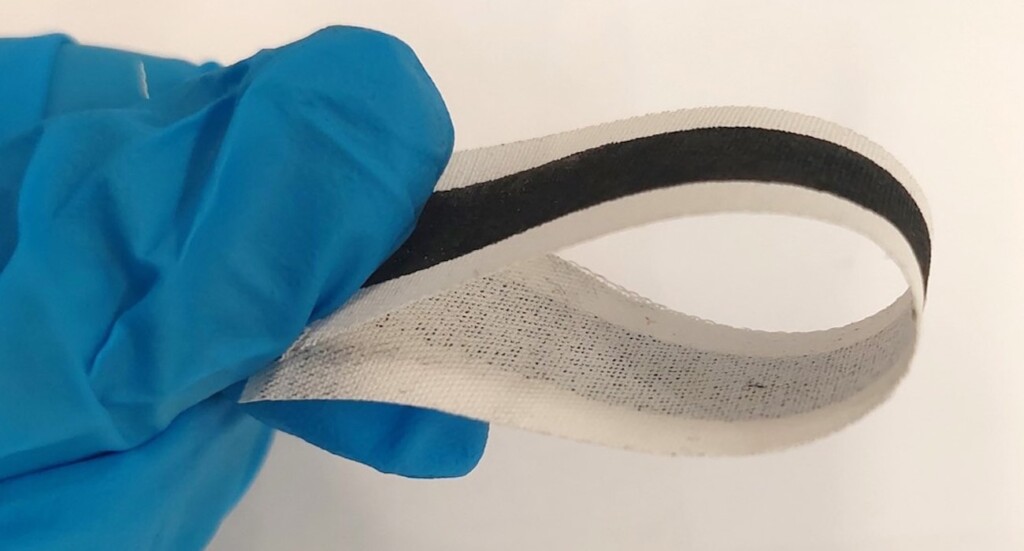

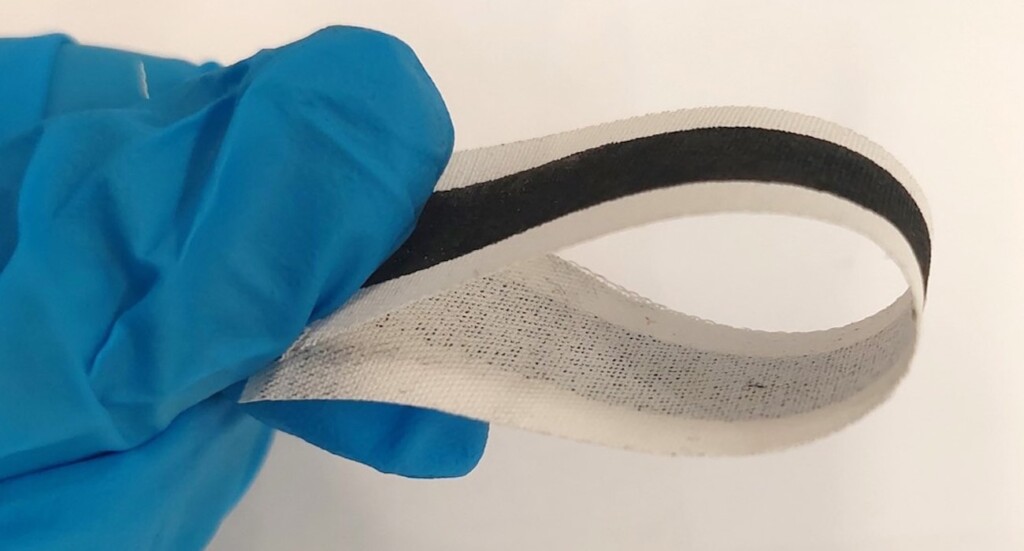

(Image: First Light Fusion)Scientists Develop Biodegradable Smart Textile–A Big Leap Forward for Eco-Friendly Wearable Technology

Flexible inkjet printed E-textile – Credit: Marzia Dulal

Flexible inkjet printed E-textile – Credit: Marzia Dulal Gloves with e-textile sensors monitoring heart rate – Credit: Marzia Dulal

Gloves with e-textile sensors monitoring heart rate – Credit: Marzia Dulal Four strips in a variety of decomposed states, during four months of decomposition – Credit: Marzia Dulal

Four strips in a variety of decomposed states, during four months of decomposition – Credit: Marzia DulalConservationist Hail Recovery of 150 Struggling Species Thanks to Projects by Natural England

A pearl-bordered fritillary – credit, Devon Wildlife Trust

A pearl-bordered fritillary – credit, Devon Wildlife Trust Wetland habitat creation to benefit water vole – credit, Nottinghamshire Wildlife Trust

Wetland habitat creation to benefit water vole – credit, Nottinghamshire Wildlife Trust

Volunteers planting marsh violet – credit, Neil Harris, National Trust images

Volunteers planting marsh violet – credit, Neil Harris, National Trust imagesUK’s Rarest Breeding Birds Raise Chicks for First Time in Six Years

A male Montagu’s harrier in a wheat field – credit, Sumeetmoghe CC 4.0. BY-SA

A male Montagu’s harrier in a wheat field – credit, Sumeetmoghe CC 4.0. BY-SAScientists Develop Biodegradable Smart Textile–A Big Leap Forward for Eco-Friendly Wearable Technology

Flexible inkjet printed E-textile – Credit: Marzia Dulal

Flexible inkjet printed E-textile – Credit: Marzia Dulal Gloves with e-textile sensors monitoring heart rate – Credit: Marzia Dulal

Gloves with e-textile sensors monitoring heart rate – Credit: Marzia Dulal Four strips in a variety of decomposed states, during four months of decomposition – Credit: Marzia Dulal

Four strips in a variety of decomposed states, during four months of decomposition – Credit: Marzia DulalUK Zoo Helps Hatch Three of World's Rarest Birds–Blue-Eyed Doves–with Only 11 Left in Wild

Columbina cyanopis, or the blue-eyed dove, in the Rolinha do Planalto Natural Reserve – credit, Hector Bottai CC BY-SA 4.0.

Columbina cyanopis, or the blue-eyed dove, in the Rolinha do Planalto Natural Reserve – credit, Hector Bottai CC BY-SA 4.0.World's First Diamond Battery Could Power Spacecraft and Pacemakers for Thousands of Years

GNN-created image

GNN-created imageGiving blood could be good for your health – new research

Blood donation is widely recognised as a life-saving act, replenishing hospital supplies and aiding patients. But could donating blood also benefit the donor?

Frequent blood donors may experience subtle genetic changes that could lower their risk of developing blood cancers, according to new research from the Francis Crick Institute in London. Alongside this, a growing body of evidence highlights a range of health benefits associated with regular donation.

As we age, our blood-forming stem cells naturally accumulate mutations, a process known as clonal haematopoiesis. Some of these mutations increase the risk of diseases such as leukaemia. However, the new Francis Crick Institute study has identified an intriguing difference in frequent blood donors.

The study compared two groups of healthy male donors in their 60s. One group had donated blood three times a year for 40 years, while the other had given blood only about five times in total. Both groups had a similar number of genetic mutations, but their nature differed. Nearly 50% of frequent donors carried a particular class of mutation not typically linked to cancer, compared with 30% of the infrequent donors.

It is thought that regular blood donation encourages the body to produce fresh blood cells, altering the genetic landscape of stem cells in a potentially beneficial way.

In laboratory experiments, these mutations behaved differently from those commonly associated with leukaemia, and when injected into mice, stem cells from frequent donors were more efficient at producing red blood cells. While these findings are promising, further research is needed to determine whether donating blood actively reduces cancer risk.

Each time a person donates blood, the body quickly begins the process of replacing lost blood cells, triggering the bone marrow to generate fresh ones. This natural renewal process may contribute to healthier, more resilient blood cells over time.

Some evidence even suggests that blood donation could improve insulin sensitivity, potentially playing a role in reducing the risk of type 2 diabetes, though research is still underway.

For years, scientists have speculated about a possible link between blood donation and cardiovascular health. One of the key factors in heart disease is blood viscosity — how thick or thin the blood is. When blood is too thick, it flows less efficiently, increasing the risk of clotting, high blood pressure and stroke. Regular blood donation helps to reduce blood viscosity, making it easier for the heart to pump and lowering the risk of cardiovascular complications.

There is also growing evidence that blood donation may help regulate iron levels in the body, another factor linked to heart disease. While iron is essential for oxygen transport in the blood, excessive iron accumulation has been associated with oxidative stress and inflammation, both of which contribute to heart disease. By shedding iron through donation, donors may be reducing their risk of these iron-related complications.

Some studies have even suggested a potential link between blood donation and lower blood pressure, particularly in people with hypertension. Though not a substitute for medication or lifestyle changes, donating blood may be another way to assist overall cardiovascular health.

Donors may not realise it, but every time they give blood, they receive a mini health screening. Before donation, blood pressure, haemoglobin levels and pulse are checked, and in some cases, screenings for infectious diseases are performed. While not a replacement for regular check-ups, it can serve as an early warning system for potential health issues.

Correlation or causation?

Of course, an important question remains: do these health benefits arise because of blood donation itself, or are they simply a reflection of the “healthy donor effect”? Blood donors must meet strict eligibility criteria. People with chronic illnesses, certain infections or a history of cancer are usually not allowed to donate. This means that those who donate regularly may already be healthier than the general population.

Regardless of whether blood donation confers direct health benefits, its life-saving effect on others is undeniable. In the UK, NHS Blood and Transplant has warned that blood stocks are critically low, urging more people to donate.

If future research confirms that donating blood has measurable advantages for donors as well, it could serve as an even greater incentive for participation. For now, the best reason to donate remains the simplest one: it saves lives.![]()

Michelle Spear, Professor of Anatomy, University of Bristol

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.