Superb fairy-wrens attacking a taxidermied shining bronze-cuckoo. William Feeney, CC BY

Superb fairy-wrens attacking a taxidermied shining bronze-cuckoo. William Feeney, CC BYLanguage enables us to connect with each other and coordinate to achieve incredible feats. Our ability to communicate abstract concepts is often seen as a defining feature of our species, and one that separates us from the rest of life on Earth.

This is because while the ability to pair an arbitrary sound with a specific meaning is widespread in human language, it is rarely seen in other animal communication systems. Several recent studies have shown that birds, chimpanzees, dolphins, and elephants also do it. But how such a capacity emerges remains a mystery.

While language is characterised by the widespread use of sounds that have a learned association with the item they refer to, humans and animals also produce instinctive sounds. For example, a scream made in response to pain. Over 150 years ago, naturalist Charles Darwin suggested the use of these instinctive sounds in a new context could be an important step in the development of language-like communication.

In our new study, published today in Nature Ecology and Evolution, we describe the first example of an animal vocalisation that contains both instinctive and learned features – similar to the stepping stone Darwin envisioned.

A unique call towards a unique threat

Birds have a variety of enemies, but brood parasites are unique.

Brood parasites, such as cuckoos, are birds that reproduce by laying their egg in the nest of another species and manipulating the unsuspecting host to incubate their egg and raise their offspring. The first thing a baby cuckoo does after it hatches is heave the other baby birds out of the nest, claiming the effort of its unsuspecting foster parents all to itself.

The high cost of brood parasitism makes it an excellent study system to explore how evolution works in the wild.

For example, our past work has shown that in Australia, the superb fairy-wren has evolved a unique call it makes when it sees a cuckoo. When other fairy-wrens hear this alarm call, they quickly come in and attack the cuckoo.

During these earlier experiments, we couldn’t help but notice other species were responding to this call and making a very similar call themselves. What’s more, discussions with collaborators who were working in countries as far away as China, India and Sweden suggested the birds there were also making a very similar call – and also only towards cuckoos.

Birds from around the world use the same call

First, we explored online wildlife media databases to see if there were other examples of this call towards brood parasites. We found 21 species that produce this call towards their brood parasites, including cuckoos and parasitic finches. Some of these birds were closely related and lived nearby each other, but others shared a last common ancestor over 50 million years ago and live on different continents.

For example, this is a superb fairy-wren responding to a shining bronze-cuckoo in Australia.

And this is a tawny-flanked prinia responding to a cuckoo finch in Zambia.

As vocalisations exist to communicate information, we suspected this call either functioned to attract the attention of their own or other species.

To compare these possibilities, we used a known database of the world’s brood parasites and hosts. If this call exists to communicate information within a species, we expected the species that produce it should be more cooperative, because more birds are better at defending their nest.

We did not find this. Instead, we found that species that produce this call exist in areas with more brood parasites and hosts, suggesting it exists to enable cooperation across different species that are targeted by brood parasites.

Communicating across species to defend against a common threat

To test whether these calls were produced uniquely towards cuckoos in multiple species, we conducted experiments in Australia.

When we presented superb fairy-wrens or white-browed scrubwrens with a taxidermied cuckoo, they made this call and tried to attack it. By contrast, when they were presented with other taxidermied models, such as a predator, this call was very rarely produced.

When we presented the fairy-wrens and scrubwrens with recordings of the call, they responded strongly. This suggests both species produce the call almost exclusively towards cuckoos, and when they hear it they respond predictably.

If this call is something like a “universal word” for a brood parasite across birds, we should expect different species to respond equally to hearing it – even when it is produced by a species they have never seen before. We found exactly this: when we played calls from Australia to birds in China (and vice-versa) they responded the same.

This suggests different species from all around the world use this call because it provides specific information about the presence of a brood parasite.

Superb fairy-wrens attacking a taxidermied shining bronze-cuckoo. William Feeney, CC BY

Superb fairy-wrens attacking a taxidermied shining bronze-cuckoo. William Feeney, CC BYInsights into the origins of language

Our study suggests that over 20 species of birds from all around the world that are separated by over 50 million years of evolution use the same call when they see their respective brood parasite species.

This is fascinating in and of itself. But while these birds know how to respond to the call, our past work has shown that birds that have never seen a cuckoo do not produce this call, but they do after watching others produce it when there is a cuckoo nearby.

In other words, while the response to the call is instinctive, producing the call itself is learned.

Whereas vocalisations are normally either instinctive or learned, this is the first example of an animal vocalisation across species that has both instinctive and learned components. This is important, because it appears to represent a midpoint between the types of vocalisations that are common in animal communication systems and human language.

So, Darwin may have been right about language all along.![]()

William Feeney, Research fellow, Environmental Futures Research Institute, Griffith University; Estación Biológica de Doñana (EBD-CSIC); James Kennerley, Postdoctoral Fellow, Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Cornell University, and Niki Teunissen, Postdoctoral research fellow, Monash University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

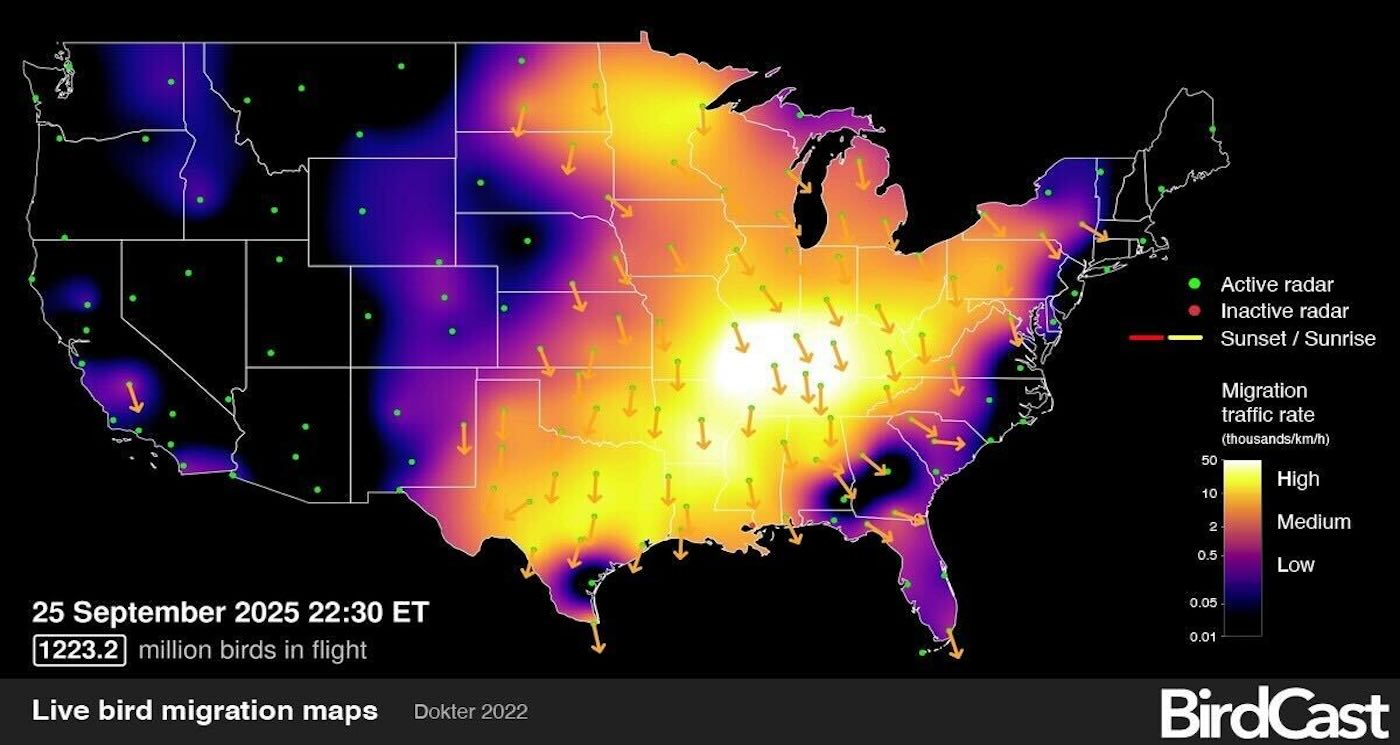

BirdCast

BirdCast A male Montagu’s harrier in a wheat field – credit,

A male Montagu’s harrier in a wheat field – credit,