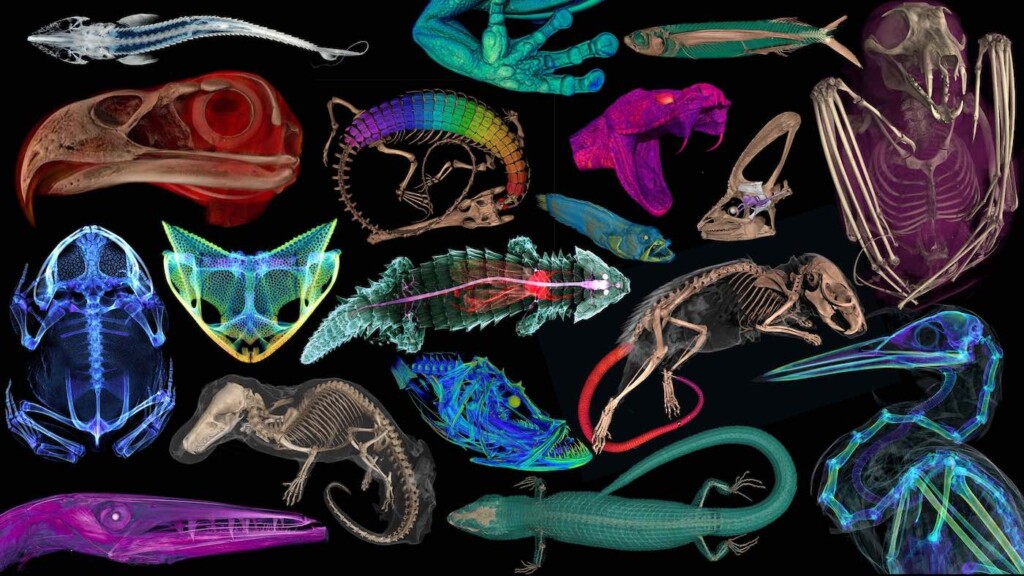

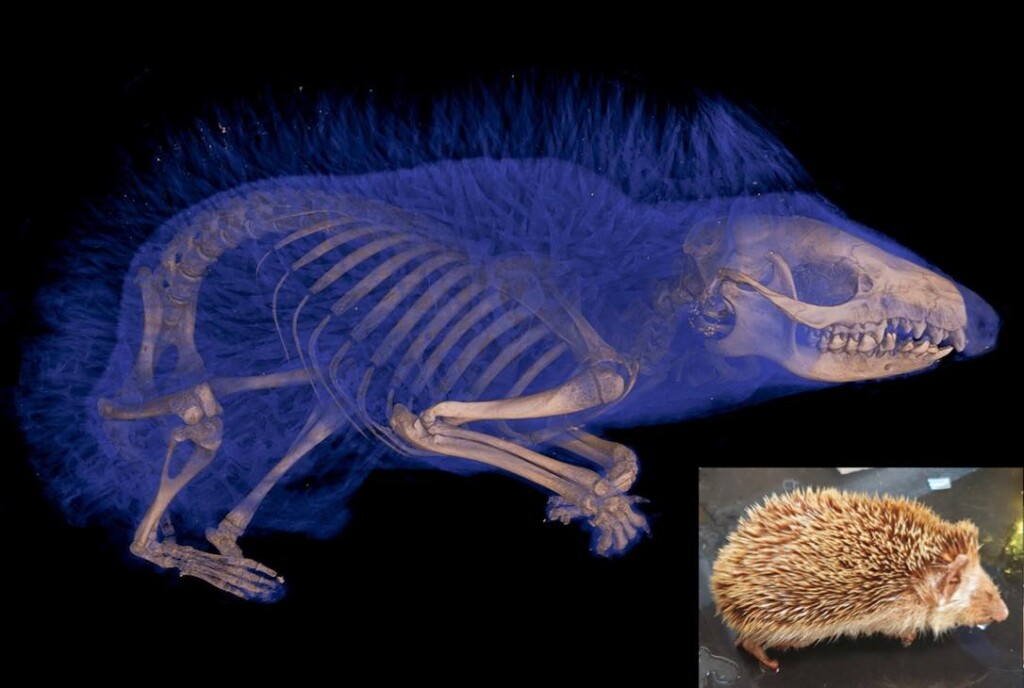

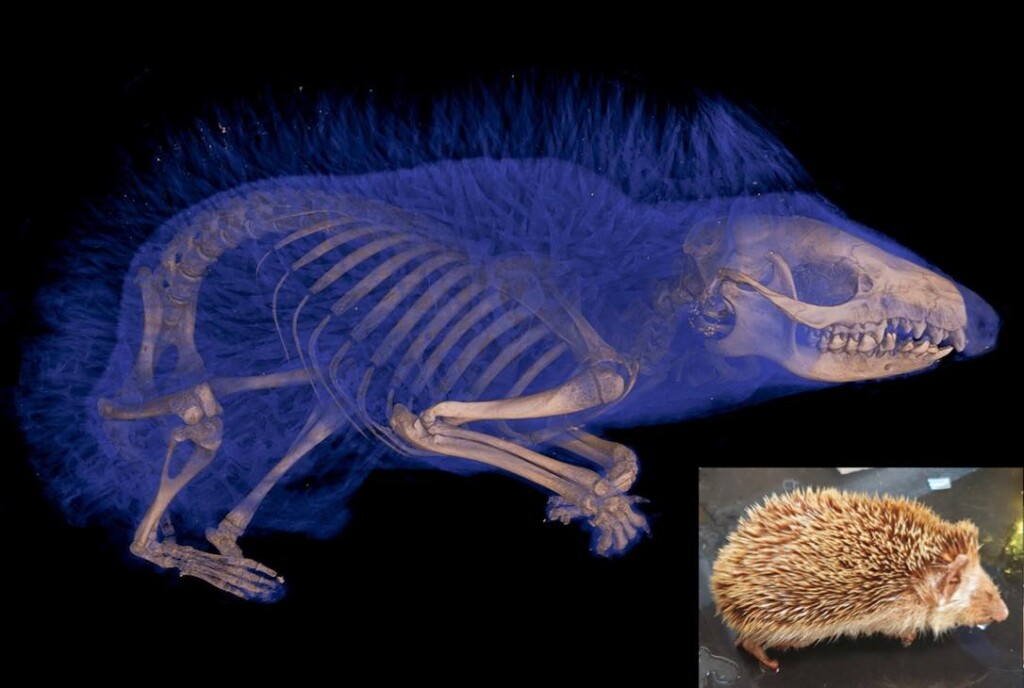

3D scanned creatures by oVert – Released by Florida Museum of Natural History / SWNS

An incredible new project has scanned thousands of creatures to advance scientific research and provide colorful images to the world. Natural history museums have entered a new stage of scientific discovery and accessibility with the completion of openVertebrate (oVert), a five-year collaborative project among 18 institutions to create 3D reconstructions of vertebrate specimens and make them freely available online. Now, researchers have published a summary of the project in the journal BioScience reviewing the specimens they’ve scanned to date, offering a glimpse of how the data might be used to ask newquestions and spur the development of innovative technology. “When people first collected these specimens, they had no idea what the future would hold for them,” said Edward Stanley, co-principal investigator of the oVert project and associate scientist at the Florida Museum of Natural History. Such museums got their start in the 16th century as cabinets of curiosity, in which a few wealthy individuals amassed rare and exotic specimens, which they kept mostly to themselves. Since then, museums have become a resource for the public to learn about biodiversity. But, the majority of museum collections remain behind closed doors—accessible only to scientists who must either travel to see them or ask that a small number of specimens be mailed on loan—and oVert wants to change that. “Now we have scientists, teachers, students and artists around the world using these data remotely,” said David Blackburn, lead principal investigator of the oVert project and curator of herpetology at the Florida Museum. Beginning in 2017, the oVert team members took CT scans of more than 13,000 specimens, with vertebrate species across the tree of life, including over half the genera of all amphibians, reptiles, fishes, and mammals.

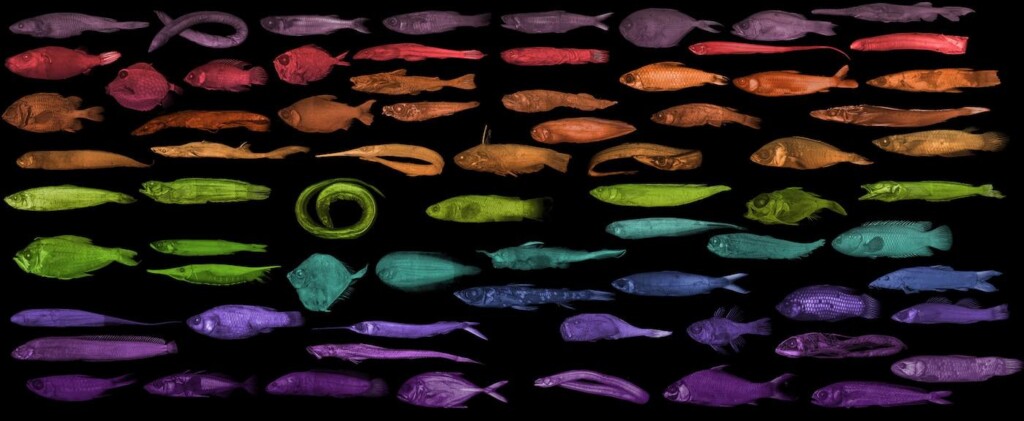

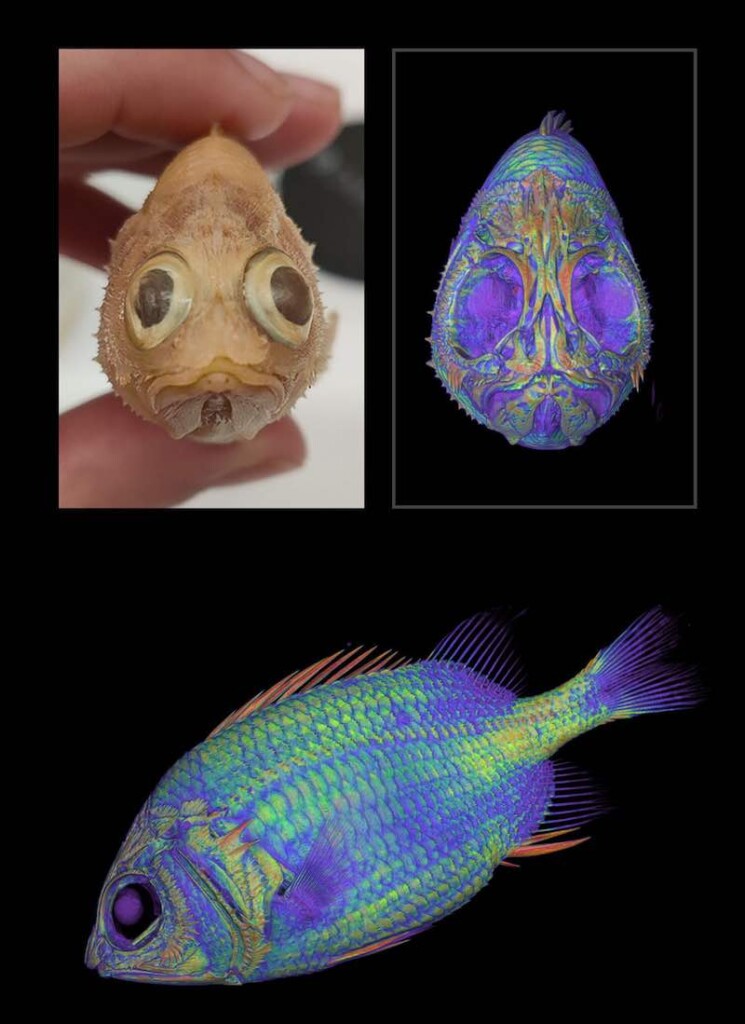

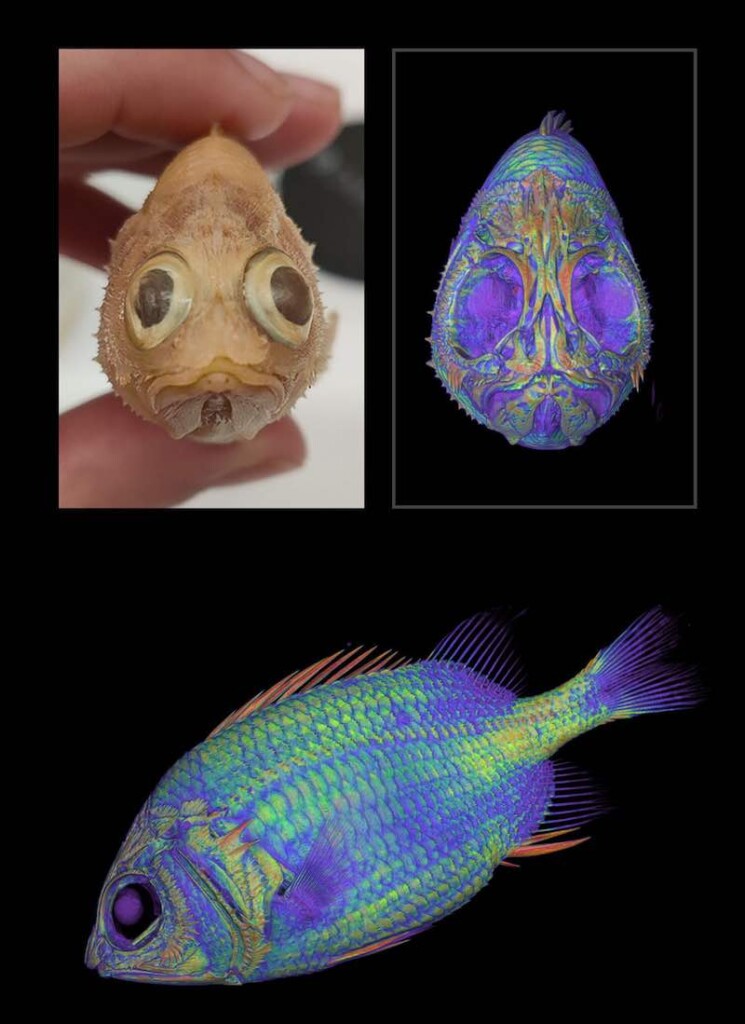

A collage of scanned fish from oVert – Released by Florida Museum of Natural History / SWNS

CT scanners use high-energy X-rays to peer past an organism’s exterior and view the dense bone structure beneath. Some specimens were also stained with a contrast-enhancing solution for visualizing soft tissues, like skin, muscle, and other organs. The models give an intimate look at internal portions of a specimen that could previously only be observed through destructive dissection and tissue sampling. “You want to protect specimens, but you also want to have people use them,” Blackburn said. “oVert is a way of reducing the wear and tear on samples while also increasing access, and it’s the next logical step in the

Hedgehog CT scan from oVert – Florida Museum of Natural History / SWNS

mission of museum collections.” Skeletons too large to fit into a CT scanner, like a humpback whale, were painstakingly taken apart so that 3D models of each individual bone could be scanned and reassembled. “These are not things you put in boxes and loan,” Blackburn pointed out. A set of iconic Galapagos tortoises at the California Academy of Sciences were each photographed in a 360-degree rotation. Photographing their undersides was problematic, as their curved shells made it impossible to keep them upright. After a few trial-and-error runs, they settled on placing the specimens on top of inflatable swimming tubes. Scientists have already used data from the project to gain astonishing insights into the natural world. Watch the incredible video below, and learn more at the bottom…In 2023, Edward Stanley was conducting routine CT scans of spiny mice and was surprised to find their tails were covered with an internal coat of bony plates, called osteoderms. Before this discovery, armadillos were considered to be the only living mammals with these structures. “All kinds of things jump out at you when you’re when you’re scanning,” Stanley said. “I study osteoderms, and through kismet or fate, I happened to be the one scanning those particular specimens on that particular day and noticed something strange about their tails on the X-ray. “That happens all the time. We’ve found all sorts of strange, unexpected things.”oVert scans were used to determine what killed a rim rock crown snake, considered to be the rarest snake species in North America. Another study showed that a group of frogs called pumpkin toadlets had become so small that the fluid-filled canals in their ears that confer balance no longer functioned properly, causing them to crash-land when jumping. One study of 500 oVert specimens revealed that frogs have lost and regained teeth more than 20 times throughout their evolutionary history. Other researchers concluded that Spinosaurus, a massive dinosaur that was larger than Tyrannosaurus rex and thought to be aquatic, would have actually been a poor swimmer, and thus likely stayed on land. And the list goes on, full of insights and ideas that would have been impossible or impractical before the project’s outset. “Now that we’ve been working on this for so long, we have a broad scaffold that allows us to take a broader view of

Fish CT scan from oVert – Florida Museum of Natural History / SWNS

evolutionary questions,” Stanley said. Artists and teachers are benefitting too Funded in part by the National Science Foundation, the value of the oVert project extends beyond science. Artists have used the 3D models to create realistic animal replicas, photographs of oVert specimens have been displayed as museum exhibits, and specimens have been incorporated into virtual reality headsets that give users the chance to interact with and manipulate them. A high school teacher in Cincinnati says it’s been a game-changer for her studies on evolution. “I teach juniors and seniors, and I absolutely love them, but they can be a tough audience,” said Jennifer Broo. “They know when things are fake, which makes them less engaged. Using the oVert models, my class has gotten so much better because I have had the opportunities to work with and expose my students to real data.”Visit Sketchfab to view a sample of 3D interactive models. At MorphoSource you can access the full openVertebrate repository.Scientists Have 3D-Scanned Thousands of Creatures Creating Incredibly Intricate Images Anyone Can Access for Free