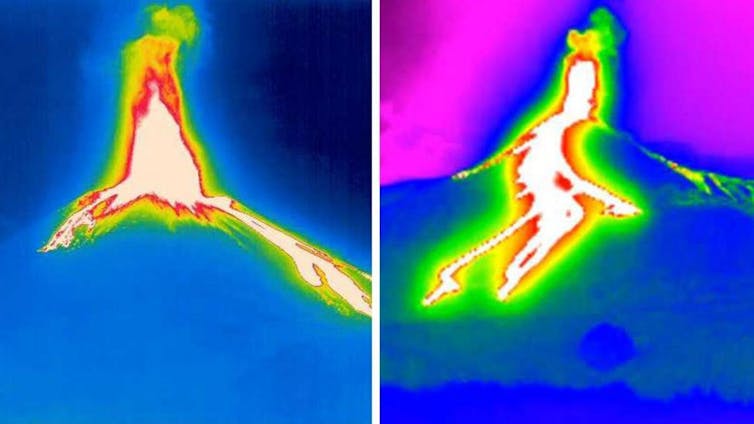

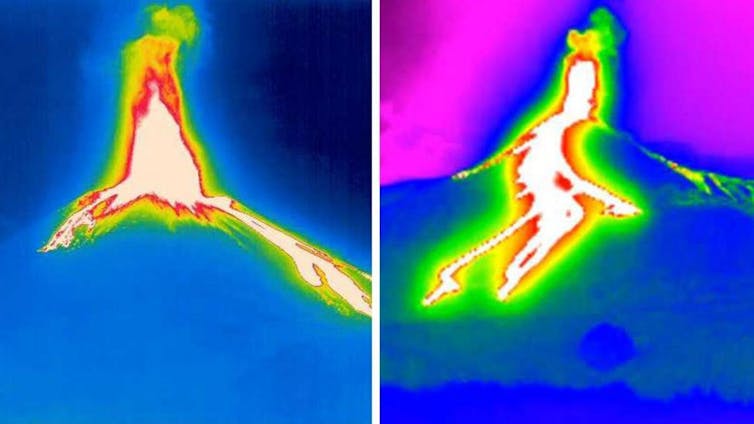

Thermal camera images show the eruption and flows of lava down the side of Mount Etna. National Institute of Geophysics and Volcanology, CC BY

Thermal camera images show the eruption and flows of lava down the side of Mount Etna. National Institute of Geophysics and Volcanology, CC BYTeresa Ubide, The University of Queensland

On Monday morning local time, a huge cloud of ash, hot gas and rock fragments began spewing from Italy’s Mount Etna.

An enormous plume was seen stretching several kilometres into the sky from the mountain on the island of Sicily, which is the largest active volcano in Europe.

While the blast created an impressive sight, the eruption resulted in no reported injuries or damage and barely even disrupted flights on or off the island. Mount Etna eruptions are commonly described as “Strombolian eruptions” – though as we will see, that may not apply to this event.

What happened at Etna?

The eruption began with an increase of pressure in the hot gases inside the volcano. This led to the partial collapse of part of one of the craters atop Etna.

The collapse allowed what is called a pyroclastic flow: a fast-moving cloud of ash, hot gas and fragments of rock bursting out from inside the volcano.

Thermal camera images show the eruption and flows of lava down the side of Mount Etna. National Institute of Geophysics and Volcanology, CC BY

Thermal camera images show the eruption and flows of lava down the side of Mount Etna. National Institute of Geophysics and Volcanology, CC BYNext, lava began to flow in three different directions down the mountainside. These flows are now cooling down. On Monday evening, Italy’s National Institute of Geophysics and Volcanology announced the volcanic activity had ended.

Etna is one of the most active volcanoes in the world, so this eruption is reasonably normal.

What is a Strombolian eruption?

Volcanologists classify eruptions by how explosive they are. More explosive eruptions tend to be more dangerous, because they move faster and cover a larger area.

At the mildest end are Hawaiian eruptions. You have probably seen pictures of these: lava flowing sedately down the slope of the volcano. The lava damages whatever it runs into, but it’s a relatively local effect.

As eruptions grow more explosive, they send ash and rock fragments flying further afield.

At the more explosive end of the scale are Plinian eruptions. These include the famous eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79AD, described by the Roman writer Pliny the Younger, which buried the Roman towns of Pompeii and Herculaneum under metres of ash.

In a Plinian eruption, hot gas, ash, and rock can explode high enough to reach the stratosphere – and when the eruption column collapses, the debris falls to Earth and can wreak terrifying destruction over a huge area.

What about Strombolian eruptions? These relatively mild eruptions are named after Stromboli, another Italian volcano which belches out a minor eruption every 10 to 20 minutes.

In a Strombolian eruption, chunks of rock and cinders may travel tens or hundreds of metres through the air, but rarely further. The pyroclastic flow from yesterday’s eruption at Etna was rather more explosive than this – so it wasn’t strictly Strombolian.

Can we forecast volcano eruptions?

Volcanic eruptions are a bit like weather. They are very hard to predict in detail, but we are a lot better than we used to be at forecasting them.

To understand what a volcano will do in the future, we first need to know what is happening inside it right now. We can’t look inside directly, but we do have indirect measurements.

For example, before an eruption magma travels from deep inside the Earth up to the surface. On the way, it pushes rocks apart and can generate earthquakes. If we record the vibrations of these quakes, we can track the magma’s journey from the depths.

Rising magma can also make the ground near a volcano bulge upwards very slightly, by a few millimetres or centimetres. We can monitor this bulging, for example with satellites, to gather clues about an upcoming eruption.

Some volcanoes release gas even when they are not strictly erupting. We can measure the chemicals in this gas – and if they change, it can tell us that new magma is on its way to the surface.

When we have this information about what’s happening inside the volcano, we also need to understand its “personality” to know what the information means for future eruptions.

Are volcanic eruptions more common than in the past?

As a volcanologist, I often hear from people that it seems there are more volcanic eruptions now than in the past. This is not the case.

What is happening, I tell them, is that we have better monitoring systems now, and a very active global media system. So we know about more eruptions – and even see photos of them.

Monitoring is extremely important. We are fortunate that many volcanoes in places such as Italy, the United States, Indonesia and New Zealand have excellent monitoring in place.

This monitoring allows local authorities to issue warnings when an eruption is imminent. For a visitor or tourist out to see the spectacular natural wonder of a volcano, listening to these warnings is all-important.![]()

Teresa Ubide, ARC Future Fellow and Associate Professor in Igneous Petrology/Volcanology, The University of Queensland

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.