(Image: IAEA)

(Image: IAEA)

(Image: IAEA)

(Image: IAEA)

Have you ever imagined what Antarctica looks like beneath its thick blanket of ice? Hidden below are rugged mountains, valleys, hills and plains.

Some peaks, like the towering Transantarctic Mountains, rise above the ice. But others, like the mysterious and ancient Gamburtsev Subglacial Mountains in the middle of East Antarctica, are completely buried.

The Gamburtsev Mountains are similar in scale and shape to the European Alps. But we can’t see them because the high alpine peaks and deep glacial valleys are entombed beneath kilometres of ice.

How did they come to be? Typically, a mountain range will rise in places where two tectonic plates clash with each other. But East Antarctica has been tectonically stable for millions of years.

Our new study, published in Earth and Planetary Science Letters, reveals how this hidden mountain chain emerged more than 500 million years ago when the supercontinent Gondwana formed from colliding tectonic plates.

Our findings offer fresh insight into how mountains and continents evolve over geological time. They also help explain why Antarctica’s interior has remained remarkably stable for hundreds of millions of years.

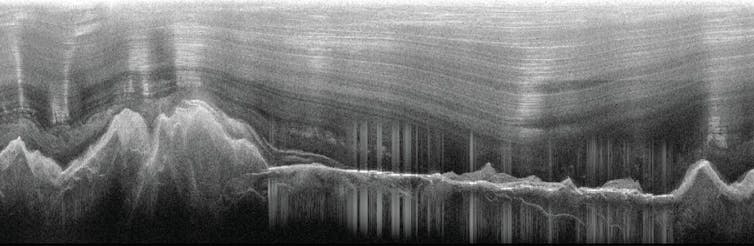

A radar image showing the Gamburtsev mountain range under layers of ice. Creyts et al., Geophysical Research Letters (2014), CC BY-SA

A radar image showing the Gamburtsev mountain range under layers of ice. Creyts et al., Geophysical Research Letters (2014), CC BY-SAThe Gamburtsev Mountains are buried beneath the highest point of the East Antarctica ice sheet. They were first discovered by a Soviet expedition using seismic techniques in 1958.

Because the mountain range is completely covered in ice, it’s one of the least understood tectonic features on Earth. For scientists, it’s deeply puzzling. How could such a massive mountain range form and still be preserved in the heart of an ancient, stable continent?

Most major mountain chains mark the sites of tectonic collisions. For example, the Himalayas are still rising today as the Indian and Eurasian plates continue to converge, a process that began about 50 million years ago.

Plate tectonic models suggest the crust now forming East Antarctica came from at least two large continents more than 700 million years ago. These continents used to be separated by a vast ocean basin.

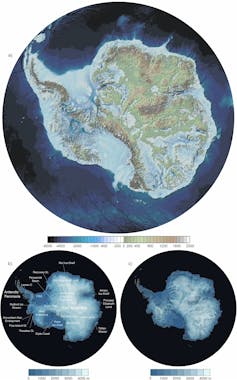

A map of the topography (a) and surface elevation (b) of Antarctica, measured in metres above sea level; (c) shows ice thickness in metres. Pritchard et al., Scientific Data (2025), CC BY

A map of the topography (a) and surface elevation (b) of Antarctica, measured in metres above sea level; (c) shows ice thickness in metres. Pritchard et al., Scientific Data (2025), CC BYThe collision of these landmasses was key to the birth of Gondwana, a supercontinent that included what is now Africa, South America, Australia, India and Antarctica.

Our new study supports the idea that the Gamburtsev Mountains first formed during this ancient collision. The colossal clash of continents triggered the flow of hot, partly molten rock deep beneath the mountains.

As the crust thickened and heated during mountain building, it eventually became unstable and began to collapse under its own weight.

Deep beneath the surface, hot rocks began to flow sideways, like toothpaste squeezed from a tube, in a process known as gravitational spreading. This caused the mountains to partially collapse, while still preserving a thick crustal “root”, which extends into Earth’s mantle beneath.

To piece together the timing of this dramatic rise and fall, we analysed tiny zircon grains found in sandstones deposited by rivers flowing from the ancient mountains more than 250 million years ago. These sandstones were recovered from the Prince Charles Mountains, which poke out of the ice hundreds of kilometres away.

Zircons are often called “time capsules” because they contain minuscule amounts of uranium in their crystal structure, which decays at a known rate and allows scientists to determine their age with great precision.

These zircon grains preserve a record of the mountain-building timeline: the Gamburtsev Mountains began to rise around 650 million years ago, reached Himalayan heights by 580 million years ago, and experienced deep crustal melting and flow that ended around 500 million years ago.

Most mountain ranges formed by continental collisions are eventually worn down by erosion or reshaped by later tectonic events. Because they’ve been preserved by a deep layer of ice, the Gamburtsev Subglacial Mountains are one of the best-preserved ancient mountain belts on Earth.

While it’s currently very challenging and expensive to drill through the thick ice to sample the mountains directly, our model offers new predictions to guide future exploration.

Geologists Jacqueline Halpin and Jack Mulder stand on the Denman Glacier during recent fieldwork. Jacqueline Halpin

Geologists Jacqueline Halpin and Jack Mulder stand on the Denman Glacier during recent fieldwork. Jacqueline HalpinFor instance, recent fieldwork near the Denman Glacier on East Antarctica’s coast uncovered rocks that may be related to these ancient mountains. Further analysis of these rock samples will help reconstruct the hidden architecture of East Antarctica.

Antarctica remains a continent full of geological surprises, and the secrets buried beneath its ice are only beginning to be revealed.![]()

Jacqueline Halpin, Associate Professor of Geology, University of Tasmania and Nathan R. Daczko, Professor of Earth Science, Macquarie University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

A media storm blew up in mid-March 2025 when a researcher at South Africa’s isolated Sanae IV base in Antarctica accused one of its nine team members of becoming violent.

The Conversation Africa asked geomorphologist David William Hedding, who has previously carried out research from the frozen continent, about the work researchers do in Antarctica, what conditions are like and why it matters.

Currently, the main focus of research in the Antarctic revolves around climate change because the White Continent is a good barometer for changes in global cycles. It has a unique and fragile environment. It’s an extreme climate which makes it highly sensitive to any changes in global climate and atmospheric conditions. Importantly, the Antarctic remains relatively untouched by humans, so we are able to study processes and responses of natural systems.

Also, the geographic location of Antarctic enables science that is less suitable elsewhere on the planet. An example of this is the work on space weather (primarily disturbances to the Earth’s magnetic field caused by solar activity). Studying space weather is significant because the magnetic field of the Earth can impact communication platforms, technology, infrastructure and even human health.

Currently, about 30 countries have research stations in the Antarctic but these bases serve a far wider community of researchers. Collaboration is a key component of research in the Antarctic because many study sites are isolated, logistics are a challenge and resources are typically limited.

The South African base in Antarctica, named SANAE IV usually has between 10 and 12 researchers and base personnel. This research station is situated on a nunatak (a mountain piercing through the ice) in Western Dronning Maud Land. It is an extremely remote location approximately 220km inland from the ice-shelf.

The researchers and base personnel remain in Antarctica for approximately 15 months working through the cold and dark winter months.

The biggest research finding from the Antarctic was the discovery of the ozone hole in 1985 by scientists from the British Antarctic Survey. This discovery led to the creation and implementation of the Montreal Protocol, a treaty to phase out chlorofluorocarbons (synthetic chemical compounds composed of chlorine, fluorine, and carbon) which destroy ozone. This was a major breakthrough in terms of slowly healing the ozone layer.

The second most significant piece of research to come from the Antarctic has been the use of ice cores to reconstruct past climates. Ice cores preserve air bubbles which provide a wealth of information about the conditions of the atmosphere over time. Importantly, ice cores provide an uninterrupted and detailed window into the past 1.2 million years. This is important because only by understanding past climates and the earth’s responses to those changes are we able to predict future responses. This is significant because of the imminent threats resulting from anthropogenic (human-induced) climate change.

Conducting research in the Antarctic is extremely difficult for three primary reasons: remoteness, the cold and daylight.

The remoteness of many study sites makes it difficult to reach. Distances are vast from the limited number of bases in the Antarctic. Thus, logistics for science in the Antarctic is a major challenge and requires collaboration and planning. For example, the geologists from the University of Johannesburg, who work from the SANAE IV base in Antarctica, often spend weeks in the field collecting samples. They travel significant distances via snow mobile and remain self-sufficient while conducting science in tough conditions.

These tough conditions relate specifically to the cold. Most science only occurs in the austral summer months when temperatures become marginally bearable. Also, the summer season only provides a short window in which to operate because access to Antarctic by sea is limited by extent and thickness of the sea ice.

Lastly, during summer there is 24 hours of daylight which lengthens the working day but these conditions are also short-lived.

The Antarctic is intricately linked to global systems and plays a major role in influencing these systems.

For example, climate change will cause significant melting of land-based ice in Antarctica which when added to the oceans will cause sea-level rise and disruptions to global oceanic currents. Therefore, it is critical that we obtain a better understanding of how responses of terrestrial systems, such as the Antarctic, will impact oceanic systems because ultimately changes in ocean currents will impact the oceanic food web.

In the context of climate change, sea-level rise is a major concern as it will have global impacts for society, so it is critical that the impacts are investigated to enable society to build resilience and adapt.![]()

David William Hedding, Associate Professor in Geography, University of South Africa

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

A media storm blew up in mid-March 2025 when a researcher at South Africa’s isolated Sanae IV base in Antarctica accused one of its nine team members of becoming violent.

The Conversation Africa asked geomorphologist David William Hedding, who has previously carried out research from the frozen continent, about the work researchers do in Antarctica, what conditions are like and why it matters.

Currently, the main focus of research in the Antarctic revolves around climate change because the White Continent is a good barometer for changes in global cycles. It has a unique and fragile environment. It’s an extreme climate which makes it highly sensitive to any changes in global climate and atmospheric conditions. Importantly, the Antarctic remains relatively untouched by humans, so we are able to study processes and responses of natural systems.

Also, the geographic location of Antarctic enables science that is less suitable elsewhere on the planet. An example of this is the work on space weather (primarily disturbances to the Earth’s magnetic field caused by solar activity). Studying space weather is significant because the magnetic field of the Earth can impact communication platforms, technology, infrastructure and even human health.

Currently, about 30 countries have research stations in the Antarctic but these bases serve a far wider community of researchers. Collaboration is a key component of research in the Antarctic because many study sites are isolated, logistics are a challenge and resources are typically limited.

The South African base in Antarctica, named SANAE IV usually has between 10 and 12 researchers and base personnel. This research station is situated on a nunatak (a mountain piercing through the ice) in Western Dronning Maud Land. It is an extremely remote location approximately 220km inland from the ice-shelf.

The researchers and base personnel remain in Antarctica for approximately 15 months working through the cold and dark winter months.

The biggest research finding from the Antarctic was the discovery of the ozone hole in 1985 by scientists from the British Antarctic Survey. This discovery led to the creation and implementation of the Montreal Protocol, a treaty to phase out chlorofluorocarbons (synthetic chemical compounds composed of chlorine, fluorine, and carbon) which destroy ozone. This was a major breakthrough in terms of slowly healing the ozone layer.

The second most significant piece of research to come from the Antarctic has been the use of ice cores to reconstruct past climates. Ice cores preserve air bubbles which provide a wealth of information about the conditions of the atmosphere over time. Importantly, ice cores provide an uninterrupted and detailed window into the past 1.2 million years. This is important because only by understanding past climates and the earth’s responses to those changes are we able to predict future responses. This is significant because of the imminent threats resulting from anthropogenic (human-induced) climate change.

Conducting research in the Antarctic is extremely difficult for three primary reasons: remoteness, the cold and daylight.

The remoteness of many study sites makes it difficult to reach. Distances are vast from the limited number of bases in the Antarctic. Thus, logistics for science in the Antarctic is a major challenge and requires collaboration and planning. For example, the geologists from the University of Johannesburg, who work from the SANAE IV base in Antarctica, often spend weeks in the field collecting samples. They travel significant distances via snow mobile and remain self-sufficient while conducting science in tough conditions.

These tough conditions relate specifically to the cold. Most science only occurs in the austral summer months when temperatures become marginally bearable. Also, the summer season only provides a short window in which to operate because access to Antarctic by sea is limited by extent and thickness of the sea ice.

Lastly, during summer there is 24 hours of daylight which lengthens the working day but these conditions are also short-lived.

The Antarctic is intricately linked to global systems and plays a major role in influencing these systems.

For example, climate change will cause significant melting of land-based ice in Antarctica which when added to the oceans will cause sea-level rise and disruptions to global oceanic currents. Therefore, it is critical that we obtain a better understanding of how responses of terrestrial systems, such as the Antarctic, will impact oceanic systems because ultimately changes in ocean currents will impact the oceanic food web.

In the context of climate change, sea-level rise is a major concern as it will have global impacts for society, so it is critical that the impacts are investigated to enable society to build resilience and adapt.![]()

David William Hedding, Associate Professor in Geography, University of South Africa

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

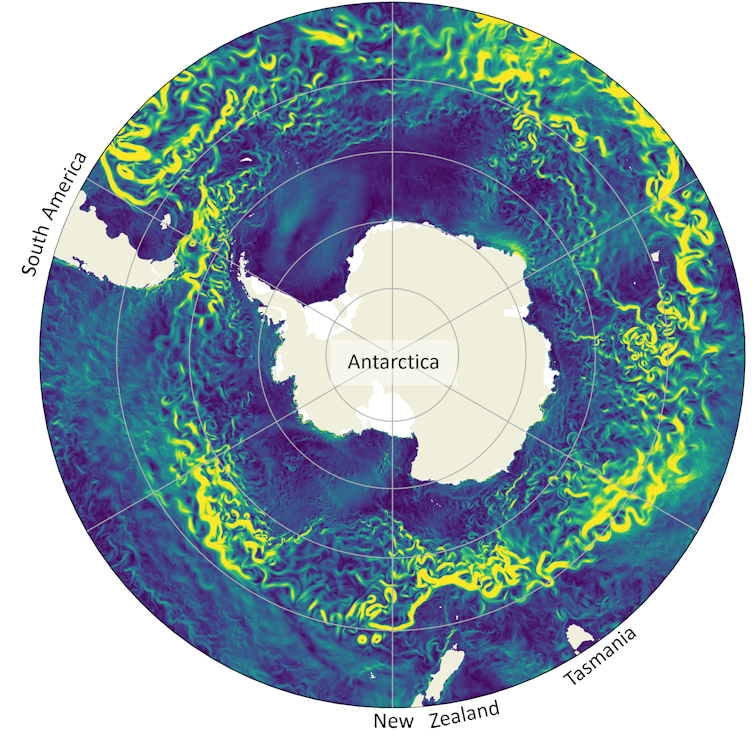

Flowing clockwise around Antarctica, the Antarctic Circumpolar Current is the strongest ocean current on the planet. It’s five times stronger than the Gulf Stream and more than 100 times stronger than the Amazon River.

It forms part of the global ocean “conveyor belt” connecting the Pacific, Atlantic, and Indian oceans. The system regulates Earth’s climate and pumps water, heat and nutrients around the globe.

But fresh, cool water from melting Antarctic ice is diluting the salty water of the ocean, potentially disrupting the vital ocean current.

Our new research suggests the Antarctic Circumpolar Current will be 20% slower by 2050 as the world warms, with far-reaching consequences for life on Earth.

The Antarctic Circumpolar Current keeps Antarctica isolated from the rest of the global ocean, and connects the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian oceans. Sohail, T., et al (2025), Environmental Research Letters., CC BY

The Antarctic Circumpolar Current keeps Antarctica isolated from the rest of the global ocean, and connects the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian oceans. Sohail, T., et al (2025), Environmental Research Letters., CC BYThe Antarctic Circumpolar Current is like a moat around the icy continent.

The current helps to keep warm water at bay, protecting vulnerable ice sheets. It also acts as a barrier to invasive species such as southern bull kelp and any animals hitching a ride on these rafts, spreading them out as they drift towards the continent. It also plays a big part in regulating Earth’s climate.

Unlike better known ocean currents – such as the Gulf Stream along the United States East Coast, the Kuroshio Current near Japan, and the Agulhas Current off the coast of South Africa – the Antarctic Circumpolar Current is not as well understood. This is partly due to its remote location, which makes obtaining direct measurements especially difficult.

Ocean currents respond to changes in temperature, salt levels, wind patterns and sea-ice extent. So the global ocean conveyor belt is vulnerable to climate change on multiple fronts.

Previous research suggested one vital part of this conveyor belt could be headed for a catastrophic collapse.

Theoretically, warming water around Antarctica should speed up the current. This is because density changes and winds around Antarctica dictate the strength of the current. Warm water is less dense (or heavy) and this should be enough to speed up the current. But observations to date indicate the strength of the current has remained relatively stable over recent decades.

This stability persists despite melting of surrounding ice, a phenomenon that had not been fully explored in scientific discussions in the past.

Advances in ocean modelling allow a more thorough investigation of the potential future changes.

We used Australia’s fastest supercomputer and climate simulator in Canberra to study the Antarctic Circumpolar Current. The underlying model, ACCESS-OM2-01, has been developed by Australian researchers from various universities as part of the Consortium for Ocean-Sea Ice Modelling in Australia.

The model captures features others often miss, such as eddies. So it’s a far more accurate way to assess how the current’s strength and behaviour will change as the world warms. It picks up the intricate interactions between ice melting and ocean circulation.

In this future projection, cold, fresh melt water from Antarctica migrates north, filling the deep ocean as it goes. This causes major changes to the density structure of the ocean. It counteracts the influence of ocean warming, leading to an overall slowdown in the current of as much as 20% by 2050.

The consequences of a weaker Antarctic Circumpolar Current are profound and far-reaching.

As the main current that circulates nutrient-rich waters around Antarctica, it plays a crucial role in the Antarctic ecosystem.

Weakening of the current could reduce biodiversity and decrease the productivity of fisheries that many coastal communities rely on. It could also aid the entry of invasive species such as southern bull kelp to Antarctica, disrupting local ecosystems and food webs.

A weaker current may also allow more warm water to penetrate southwards, exacerbating the melting of Antarctic ice shelves and contributing to global sea-level rise. Faster ice melting could then lead to further weakening of the current, commencing a vicious spiral of current slowdown.

This disruption could extend to global climate patterns, reducing the ocean’s ability to regulate climate change by absorbing excess heat and carbon in the atmosphere.

While our findings present a bleak prognosis for the Antarctic Circumpolar Current, the future is not predetermined. Concerted efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions could still limit melting around Antarctica.

Establishing long-term studies in the Southern Ocean will be crucial for monitoring these changes accurately.

With proactive and coordinated international actions, we have a chance to address and potentially avert the effects of climate change on our oceans.

The authors thank Polar Climate Senior Researcher Dr Andreas Klocker, from the NORCE Norwegian Research Centre and Bjerknes Centre for Climate Research, for his contribution to this research, and Professor Matthew England from the University of New South Wales, who provided the outputs from the model simulation for this analysis.![]()

Taimoor Sohail, Postdoctoral Researcher, School of Geography, Earth and Atmospheric Sciences, The University of Melbourne and Bishakhdatta Gayen, ARC Future Fellow & Associate Professor, Mechanical Engineering, The University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.