A drought-affected corn field in the town of Serodino, Santa Fe province, Argentina, on Thursday, Nov. 9, 2023. MUST CREDIT: Sebastian Lopez Brach/Bloomberg

A drought-affected corn field in the town of Serodino, Santa Fe province, Argentina, on Thursday, Nov. 9, 2023. MUST CREDIT: Sebastian Lopez Brach/BloombergThe world is quietly losing the land it needs to feed itself

A drought-affected corn field in the town of Serodino, Santa Fe province, Argentina, on Thursday, Nov. 9, 2023. MUST CREDIT: Sebastian Lopez Brach/Bloomberg

A drought-affected corn field in the town of Serodino, Santa Fe province, Argentina, on Thursday, Nov. 9, 2023. MUST CREDIT: Sebastian Lopez Brach/BloombergThink you’re good at multi-tasking? Here’s how your brain compensates – and how this changes with age

Arlington Research/Unsplash Peter Wilson, Australian Catholic UniversityWe’re all time-poor, so multi-tasking is seen as a necessity of modern living. We answer work emails while watching TV, make shopping lists in meetings and listen to podcasts when doing the dishes. We attempt to split our attention countless times a day when juggling both mundane and important tasks.

Arlington Research/Unsplash Peter Wilson, Australian Catholic UniversityWe’re all time-poor, so multi-tasking is seen as a necessity of modern living. We answer work emails while watching TV, make shopping lists in meetings and listen to podcasts when doing the dishes. We attempt to split our attention countless times a day when juggling both mundane and important tasks.

But doing two things at the same time isn’t always as productive or safe as focusing on one thing at a time.

The dilemma with multi-tasking is that when tasks become complex or energy-demanding, like driving a car while talking on the phone, our performance often drops on one or both.

Here’s why – and how our ability to multi-task changes as we age.

Doing more things, but less effectively

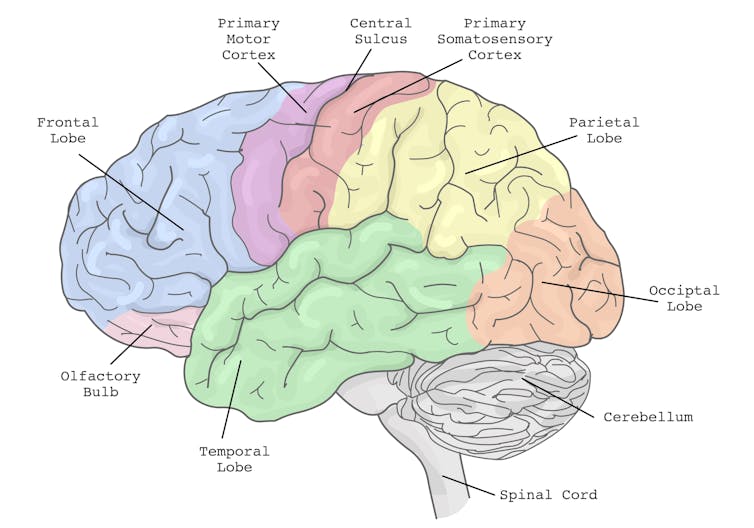

The issue with multi-tasking at a brain level, is that two tasks performed at the same time often compete for common neural pathways – like two intersecting streams of traffic on a road.

In particular, the brain’s planning centres in the frontal cortex (and connections to parieto-cerebellar system, among others) are needed for both motor and cognitive tasks. The more tasks rely on the same sensory system, like vision, the greater the interference.

The brain’s action planning centres are in the frontal cortex (blue), with reciprocal connections to parietal cortex (yellow) and the cerebellum (grey), among others. grayjay/Shutterstock

The brain’s action planning centres are in the frontal cortex (blue), with reciprocal connections to parietal cortex (yellow) and the cerebellum (grey), among others. grayjay/ShutterstockThis is why multi-tasking, such as talking on the phone, while driving can be risky. It takes longer to react to critical events, such as a car braking suddenly, and you have a higher risk of missing critical signals, such as a red light.

The more involved the phone conversation, the higher the accident risk, even when talking “hands-free”.

Having a conversation while driving slows your reaction time. GBJSTOCK/Shutterstock

Having a conversation while driving slows your reaction time. GBJSTOCK/ShutterstockGenerally, the more skilled you are on a primary motor task, the better able you are to juggle another task at the same time. Skilled surgeons, for example, can multitask more effectively than residents, which is reassuring in a busy operating suite.

Highly automated skills and efficient brain processes mean greater flexibility when multi-tasking.

Adults are better at multi-tasking than kids

Both brain capacity and experience endow adults with a greater capacity for multi-tasking compared with children.

You may have noticed that when you start thinking about a problem, you walk more slowly, and sometimes to a standstill if deep in thought. The ability to walk and think at the same time gets better over childhood and adolescence, as do other types of multi-tasking.

When children do these two things at once, their walking speed and smoothness both wane, particularly when also doing a memory task (like recalling a sequence of numbers), verbal fluency task (like naming animals) or a fine-motor task (like buttoning up a shirt). Alternately, outside the lab, the cognitive task might fall by wayside as the motor goal takes precedence.

Brain maturation has a lot to do with these age differences. A larger prefrontal cortex helps share cognitive resources between tasks, thereby reducing the costs. This means better capacity to maintain performance at or near single-task levels.

The white matter tract that connects our two hemispheres (the corpus callosum) also takes a long time to fully mature, placing limits on how well children can walk around and do manual tasks (like texting on a phone) together.

For a child or adult with motor skill difficulties, or developmental coordination disorder, multi-tastking errors are more common. Simply standing still while solving a visual task (like judging which of two lines is longer) is hard. When walking, it takes much longer to complete a path if it also involves cognitive effort along the way. So you can imagine how difficult walking to school could be.

What about as we approach older age?

Older adults are more prone to multi-tasking errors. When walking, for example, adding another task generally means older adults walk much slower and with less fluid movement than younger adults.

These age differences are even more pronounced when obstacles must be avoided or the path is winding or uneven.

Our ability to multi-task reduces with age. Shutterstock/Grizanda

Our ability to multi-task reduces with age. Shutterstock/GrizandaOlder adults tend to enlist more of their prefrontal cortex when walking and, especially, when multi-tasking. This creates more interference when the same brain networks are also enlisted to perform a cognitive task.

These age differences in performance of multi-tasking might be more “compensatory” than anything else, allowing older adults more time and safety when negotiating events around them.

Older people can practise and improve

Testing multi-tasking capabilities can tell clinicians about an older patient’s risk of future falls better than an assessment of walking alone, even for healthy people living in the community.

Testing can be as simple as asking someone to walk a path while either mentally subtracting by sevens, carrying a cup and saucer, or balancing a ball on a tray.

Patients can then practise and improve these abilities by, for example, pedalling an exercise bike or walking on a treadmill while composing a poem, making a shopping list, or playing a word game.

The goal is for patients to be able to divide their attention more efficiently across two tasks and to ignore distractions, improving speed and balance.

There are times when we do think better when moving

Let’s not forget that a good walk can help unclutter our mind and promote creative thought. And, some research shows walking can improve our ability to search and respond to visual events in the environment.

But often, it’s better to focus on one thing at a time

We often overlook the emotional and energy costs of multi-tasking when time-pressured. In many areas of life – home, work and school – we think it will save us time and energy. But the reality can be different.

Multi-tasking can sometimes sap our reserves and create stress, raising our cortisol levels, especially when we’re time-pressured. If such performance is sustained over long periods, it can leave you feeling fatigued or just plain empty.

Deep thinking is energy demanding by itself and so caution is sometimes warranted when acting at the same time – such as being immersed in deep thought while crossing a busy road, descending steep stairs, using power tools, or climbing a ladder.

So, pick a good time to ask someone a vexed question – perhaps not while they’re cutting vegetables with a sharp knife. Sometimes, it’s better to focus on one thing at a time.![]()

Peter Wilson, Professor of Developmental Psychology, Australian Catholic University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.