Decontamination of landfills and open dumpsites could prove profitable – both financially and for the environment.

Environmental pollution, health threats and scarcity of raw materials, water, food and energy are some of the greatest challenges humanity is facing today. At the same time, landfills and open dumpsites are still the dominant choice for waste disposal, despite the long-term environmental impacts in the form of greenhouse gas emissions, contaminated leachates and lost materials. Globally, the output of solid waste stood at 1.3 billion tonnes annually in 2012 and is predicted to exceed 2.2 billion by 2025. The cost of dealing with this quantity of garbage will nearly double as well, rising to $375 billion each year.

However, much of the environmentally hazardous waste that has accumulated at landfills could be recycled as energy or reused as valuable raw materials, according to Yahya Jani, doctor of environmental science and chemical engineering at Linnaeus University in the Småland region of Sweden. In his dissertation, Jani suggests "landfill mining" as a tool to achieve an enhanced circular economy model. Viewing the landfill waste as a potential resource, instead of a problem, is a common thread in his research.

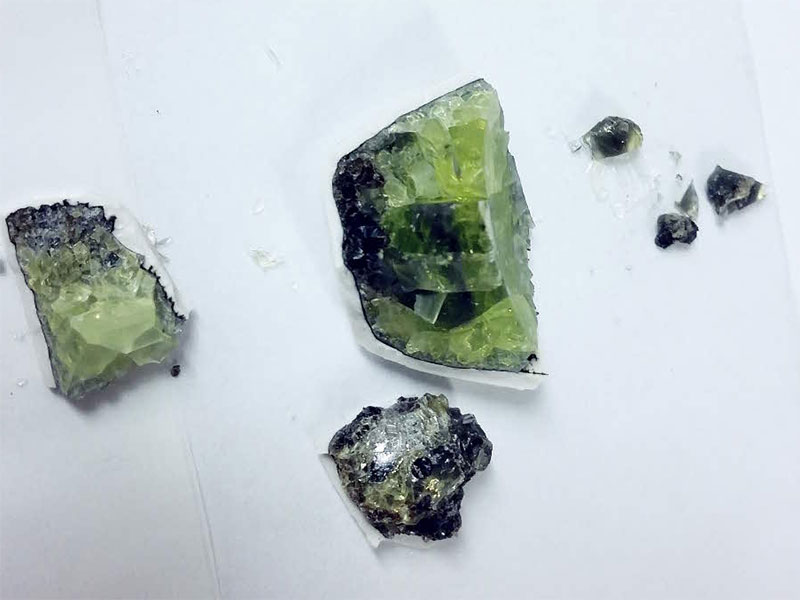

"More than 50% of the deposited waste dumped at landfills and open dump sites can be recycled as energy or reused as raw materials. These materials can be used as secondary resources in different industries, instead of being forgotten or viewed as garbage," Jani explains. His research includes the extraction of metals from Småland's art and crystal glass waste and different fine fractions. "I developed a method that enables the extraction of 99% of the metals from the glass waste that was dumped at Pukeberg's glassworks and published the results. It is the first published article in the world that deals with recycling of metals from art and crystal glass," he says.

Credit: Yahya Jani / Linnaeus University

In his research study at Glasriket, Jani also used chemical extraction to recycle materials from a mix of glass waste and soil fine fractions smaller than 2 mm. The technology involves mixing old glass waste with chemicals to reduce the melting point of the glass waste in order to extract the metals.

"The methods I developed can be used to extract metals from all types of glass – like, for instance, the glass in old TV sets and computers. This method can be further developed at an industrial facility for the recycling of both glass and metals of high purity. This can also contribute to a restoration of Småland's glass industry by providing the industry with cheap raw materials. In addition, the extraction of materials from old landfills contributes to the decontamination of these sites and reduces the environmental impact and health threats," Jani concludes.

According to the European Commission's latest figures, 60% of the annually produced waste from 500 million EU inhabitants ends up in landfills. In his dissertation, Jani shows that the extraction of valuable materials from this waste could significantly reduce the overuse of natural resources on Earth while also cutting emissions of greenhouse gases like carbon dioxide and contaminated leachates that cause water pollution. Decontamination of these sites could significantly improve both human health and the environment.

Jani's report sheds light on the need to view dumped waste as a secondary resource and landfills as "bank accounts" from which raw materials could be extracted in the future, instead of viewing them as a burden.

Credit: Yahya Jani / Linnaeus University