Photo by Christopher Michel, CC license

Photo by Christopher Michel, CC licenseIn World First, Scientists Share What Was Almost Certainly a Conversation with a Humpback Whale

Photo by Christopher Michel, CC license

Photo by Christopher Michel, CC licenseBiologist Finds Beautiful Blue Gecko, Named the New Species 'Vangoghgi'

Cnemaspis vangoghi – Akshay Khandekar

Cnemaspis vangoghi – Akshay KhandekarWe found three new species of extinct giant kangaroo – and we don’t know why they died out when their cousins survived

Artist’s impression of the prehistoric landscape and creatures that Protemnodon would have walked among. Peter Schouten

Isaac A. R. Kerr, Flinders University

Artist’s impression of the prehistoric landscape and creatures that Protemnodon would have walked among. Peter Schouten

Isaac A. R. Kerr, Flinders UniversityFor millions of years, giant animals or megafauna roamed the lands that are now Australia and New Guinea. Many were like much larger versions of modern animals.

There was a four-metre goanna called Megalania (Varanus priscus), for example, which likely ambushed its prey. This beast disappeared by around 40,000 years ago along with almost all the other megafauna aside from remnants such as the red kangaroo and the saltwater crocodile.

Some of the now-vanished kangaroo species were quite massive. The short-faced kangaroo Procoptodon goliah grew as tall as three metres and may have weighed more than 250 kilograms.

There was another genus of extinct kangaroos, Protemnodon, which were more like the grey and red roos we know today, but little has been known about their lives. In a new study, my colleagues and I describe three new species of these vanished marsupials – and shed some light on where they lived and how they got around.

A 150-year puzzle

The first species of Protemnodon were described in 1874 by the British naturalist Richard Owen. As was standard at the time, Owen focused chiefly on fossil teeth. Seeing minor differences between teeth from different fragmentary specimens, he described six species of Protemnodon.

However, Owen’s species have not stood the test of time. Our study agrees with only one of his species — Protemnodon anak. The first specimen of P. anak to be described, called the holotype, still resides in the Natural History Museum in London.

Fossils of individual Protemnodon bones are not uncommon, but more complete skeletons are rare. This has hampered palaeontologists’ efforts to study the creatures.

The question of how many species there were, and how to tell them apart, has not been fully answered. This has made it hard to say how the species differed in their size, geographic range, movement and adaptations to their natural environments.

I set out to solve this problem in my PhD project. With fellow PhD student Jacob van Zoelen, I visited the collections of 14 museums in four countries to gather data.

We have now seen just about every piece of Protemnodon that exists above ground, photographing, scanning, measuring, comparing and describing more than 800 specimens collected from all over Australia and New Guinea.

Finding the key

Among all this study, the key to the Protemnodon problem turned out to be buried in the dry bed of Lake Callabonna in northeastern South Australia. Three expeditions to Lake Callabonna from 2013 to 2019 found a megafaunal boneyard: complete skeletons of giant kangaroos, giant wombats, and Genyornis newtoni, a 250kg flightless bird, were scattered among the remains of hundreds of Diprotodon optatum, a rhino-sized marsupial herbivore. This lake likely preserves animals that died while searching for water during prolonged drought.

I accompanied the 2018 trip, which returned with all manner of amazing articulated fossils. These fossils allowed me, then a PhD student in my first year, to begin the process of picking apart the identities of the kangaroos.

Two of Richard Owen’s species, Protemnodon brehus and Protemnodon roechus, were only known from their teeth, which were extremely similar. We unearthed and compared several kangaroos with teeth that could have belonged to either of Owen’s species, but the skeletons didn’t match.

By the international rules of species naming, this meant we had to describe two new species. These are Protemnodon viator from central Australia and Protemnodon mamkurra from southern Australia.

Big kangaroos with big differences

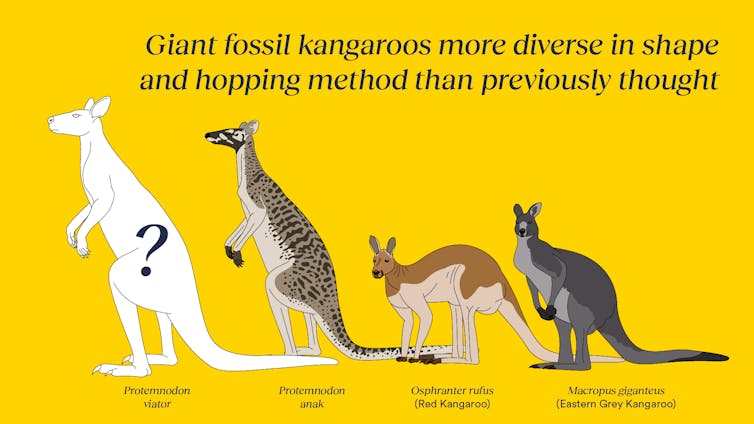

Our study reviews all species of Protemnodon, finding surprising differences. We concluded that there are seven species in the genus, adapted to live in very different environments and even hopping in different ways. This level of variation is unusual within a single genus of kangaroo.

The newly described species Protemnodon viator was bigger than its relative P. anak, and much bigger than the red and Eastern grey kangaroos we know today. Traci Klarenbeek

The newly described species Protemnodon viator was bigger than its relative P. anak, and much bigger than the red and Eastern grey kangaroos we know today. Traci KlarenbeekProtemnodon viator was a large, long-limbed kangaroo that could hop fairly quickly and efficiently. Its name, viator, is Latin for “traveller” or “wayfarer”. Its elongated hind limbs were muscular and narrow, perfect for supporting the kangaroo as it hopped long distances.

Protemnodon viator was well-adapted to its arid central Australian habitat, living in similar areas to the red kangaroos of today. Protemnodon viator was much bigger, however, weighing up to 170 kg, about twice as much as the largest male red kangaroos.

Our study suggests two or three species of Protemnodon may have been mostly quadrupedal, moving something like a quokka or potoroo – bounding on four legs at times, and hopping on two legs at others.

The newly described Protemnodon mamkurra is likely one of these. A large but thick-boned and robust kangaroo, it was probably fairly slow-moving and inefficient. It may have hopped only rarely, perhaps just when startled.

The best fossils of this species come from southeastern South Australia, on the land of the Boandik people. The species name, mamkurra, was chosen by Boandik elders and language experts in the Burrandies Corporation. It means “great kangaroo” in Bunganditj language.

The third of our newly described species is Protemnodon dawsonae, a woodland-dwelling kangaroo from eastern Australia and the probable ancestor of P. viator and P. mamkurra. It is named for kangaroo palaeontologist Lyndall Dawson.

By about 40,000 years ago, despite their many differences, all Protemnodon were extinct on mainland Australia. We don’t yet know why they died out when similar animals such as wallaroos and grey kangaroos survived – but our study may open the door for further Protemnodon research that will find out more about how they lived and why they died.![]()

Isaac A. R. Kerr, Research Assistant at Flinders University Palaeontology Laboratory, Flinders University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

How Singapore Became an Unexpected Stronghold for a Critically Endangered Bird

Straw-headed bulbul – credit Michael MK Khor CC 2.0. Flickr

Straw-headed bulbul – credit Michael MK Khor CC 2.0. FlickrThe first pig kidney has been transplanted into a living person. But we’re still a long way from solving organ shortages

In a world first, we heard last week that US surgeons had transplanted a kidney from a gene-edited pig into a living human. News reports said the procedure was a breakthrough in xenotransplantation – when an organ, cells or tissues are transplanted from one species to another.

Champions of xenotransplantation regard it as the solution to organ shortages across the world. In December 2023, 1,445 people in Australia were on the waiting list for donor kidneys. In the United States, more than 89,000 are waiting for kidneys.

One biotech CEO says gene-edited pigs promise “an unlimited supply of transplantable organs”.

Not, everyone, though, is convinced transplanting animal organs into humans is really the answer to organ shortages, or even if it’s right to use organs from other animals this way.

There are two critical barriers to the procedure’s success: organ rejection and the transmission of animal viruses to recipients.

But in the past decade, a new platform and technique known as CRISPR/Cas9 – often shortened to CRISPR – has promised to mitigate these issues.

What is CRISPR?

CRISPR gene editing takes advantage of a system already found in nature. CRISPR’s “genetic scissors” evolved in bacteria and other microbes to help them fend off viruses. Their cellular machinery allows them to integrate and ultimately destroy viral DNA by cutting it.

In 2012, two teams of scientists discovered how to harness this bacterial immune system. This is made up of repeating arrays of DNA and associated proteins, known as “Cas” (CRISPR-associated) proteins.

When they used a particular Cas protein (Cas9) with a “guide RNA” made up of a singular molecule, they found they could program the CRISPR/Cas9 complex to break and repair DNA at precise locations as they desired. The system could even “knock in” new genes at the repair site.

In 2020, the two scientists leading these teams were awarded a Nobel prize for their work.

In the case of the latest xenotransplantation, CRISPR technology was used to edit 69 genes in the donor pig to inactivate viral genes, “humanise” the pig with human genes, and knock out harmful pig genes.

A busy time for gene-edited xenotransplantation

While CRISPR editing has brought new hope to the possibility of xenotransplantation, even recent trials show great caution is still warranted.

In 2022 and 2023, two patients with terminal heart diseases, who were ineligible for traditional heart transplants, were granted regulatory permission to receive a gene-edited pig heart. These pig hearts had ten genome edits to make them more suitable for transplanting into humans. However, both patients died within several weeks of the procedures.

Earlier this month, we heard a team of surgeons in China transplanted a gene-edited pig liver into a clinically dead man (with family consent). The liver functioned well up until the ten-day limit of the trial.

How is this latest example different?

The gene-edited pig kidney was transplanted into a relatively young, living, legally competent and consenting adult.

The total number of gene edits edits made to the donor pig is very high. The researchers report making 69 edits to inactivate viral genes, “humanise” the pig with human genes, and to knockout harmful pig genes.

Clearly, the race to transform these organs into viable products for transplantation is ramping up.

From biotech dream to clinical reality

Only a few months ago, CRISPR gene editing made its debut in mainstream medicine.

In November, drug regulators in the United Kingdom and US approved the world’s first CRISPR-based genome-editing therapy for human use – a treatment for life-threatening forms of sickle-cell disease.

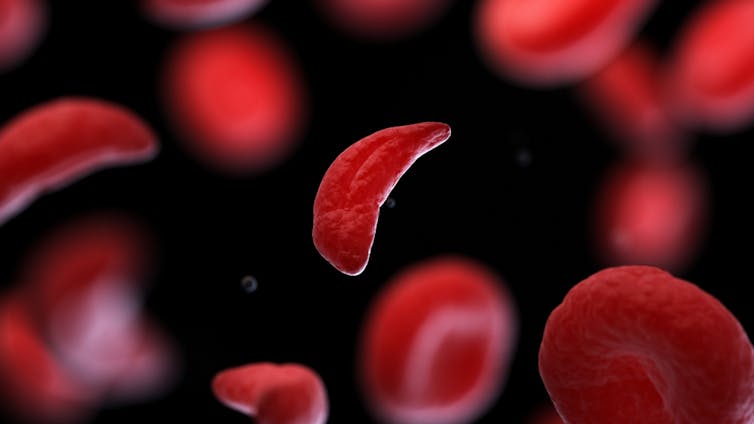

The treatment, known as Casgevy, uses CRISPR/Cas-9 to edit the patient’s own blood (bone-marrow) stem cells. By disrupting the unhealthy gene that gives red blood cells their “sickle” shape, the aim is to produce red blood cells with a healthy spherical shape.

Although the treatment uses the patient’s own cells, the same underlying principle applies to recent clinical xenotransplants: unsuitable cellular materials may be edited to make them therapeutically beneficial in the patient.

CRISPR technology is aiming to restore diseased red blood cells to their healthy round shape. Sebastian Kaulitzki/Shutterstock

CRISPR technology is aiming to restore diseased red blood cells to their healthy round shape. Sebastian Kaulitzki/ShutterstockWe’ll be talking more about gene-editing

Medicine and gene technology regulators are increasingly asked to approve new experimental trials using gene editing and CRISPR.

However, neither xenotransplantation nor the therapeutic applications of this technology lead to changes to the genome that can be inherited.

For this to occur, CRISPR edits would need to be applied to the cells at the earliest stages of their life, such as to early-stage embryonic cells in vitro (in the lab).

In Australia, intentionally creating heritable alterations to the human genome is a criminal offence carrying 15 years’ imprisonment.

No jurisdiction in the world has laws that expressly permits heritable human genome editing. However, some countries lack specific regulations about the procedure.

Is this the future?

Even without creating inheritable gene changes, however, xenotransplantation using CRISPR is in its infancy.

For all the promise of the headlines, there is not yet one example of a stable xenotransplantation in a living human lasting beyond seven months.

While authorisation for this recent US transplant has been granted under the so-called “compassionate use” exemption, conventional clinical trials of pig-human xenotransplantation have yet to commence.

But the prospect of such trials would likely require significant improvements in current outcomes to gain regulatory approval in the US or elsewhere.

By the same token, regulatory approval of any “off-the-shelf” xenotransplantation organs, including gene-edited kidneys, would seem some way off.![]()

Christopher Rudge, Law lecturer, University of Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.